![]()

CHAPTER 1

Old Posen and Young Ernst

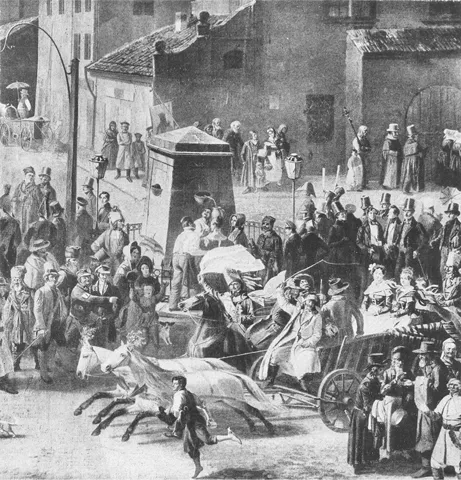

AROUND 1835 AN ARTIST FROM POSEN PAINTED A CANVAS representing a scene in Posen’s market square (fig. 2). A carriage bearing two aristocratic ladies is rushing through. It is drawn by galloping thoroughbred horses and accompanied by a hussar on a rearing steed. Behind the carriage stand several prosperous men, probably local eminences, and a less prosperous group has its attention fixed on the carriage. The artist seemed intent on portraying various elements of the city’s society, and he also depicted Jews. Three shabbily dressed men can be seen in a corner of the painting who appear as if they could have played in Fiddler on the Roof. Indifferent to the commotion, they are engaged in a business transaction that apparently concerns the sale of cloth and pots and pans. Ernst Kantorowicz’s grandfather, Hartwig Kantorowicz (1806–1871), was born to this milieu. He and his wife Sophie (the granddaughter of a rabbi) sold home-produced liquor from a stand in the market when they were young, around the time of the painting just described. But Hartwig was a remarkable entrepreneur; by 1845 he had gained the means to build a two-story distillery with the most technologically advanced copper apparatus. Well before his death in 1871 he had become one of the two entrepreneurs in Posen with the largest amount of capital. A grandniece remembered years later that when he relaxed in his home he wore a red fez with a black tassel. An inscription written over the entrance to the main building of his firm bore the words “Alles durch eigene Kraft”: everything through one’s own power.

Figure 2. Market Square in Posen, circa 1835. (Courtesy Salomon Ludwig Steinheim-Institut für deutsch-jüdische Geschichte an der Universität Duisburg-Essen)

Details of Hartwig’s rise “through his own power” are scanty. But the main outlines can be discerned. The Prussian province of Posnania was heavily agricultural, aside from manufacturing in or near the prosperous city of Posen. (In 1850 the population of Posen was 38,500; by 1895 it had almost doubled to 73,000.) This meant that a talented businessman could negotiate advantageous deals to purchase grain for distillation into spirits. Hartwig Kantorowicz was talented in that regard, but his true genius lay in recognizing the possibility of branching out from schnapps (hard liquor) into liqueurs. As German prosperity grew during the nineteenth century, a penchant for luxury items grew with it. Hence a market opened for more refined alcoholic beverages than schnapps—herb-flavored or fruit-flavored and suitable for serving at home (rather than in taverns) as aperitifs or after-dinner drinks. A document of 1862 referred to two of Hartwig Kantorowicz’s products: “Kümmelliqueur” and “Goldwassercrème.” The first, otherwise known as “Allasch,” was made primarily from caraway seeds, the second from an essence based on a mixture of herbs such as anise, cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves, and peppermint (and always plenty of sugar). The same document reveals that Hartwig’s products already were being exported beyond Germany to lands as distant as Australia and America.

The founding father and his wife had seven sons and a daughter (five other children died in infancy). The three sons that concern us were Max (1843–1904), Edmund (1846–1904), and Joseph (1848–1919). These assumed joint management of the firm after Hartwig’s death in 1871: the eldest as director, the other two as junior partners. Max Kantorowicz possessed the enterprising genius of his father. Sometime in the 1880s he traveled to the United States to arrange for the regular exporting to Posen of fruit juices, which made for a more varied range of liqueurs. On the same trip he arranged for the regular purchase of California wines, which were extremely cheap, in order to introduce the sale of wines as a sideline to the Kantorowicz business. So far as is known, Max was the first to introduce California wines to Europe.

A description of the Kantorowicz enterprise that appeared in a Posen newspaper in 1895 offers a good impression of what Max and his partners had accomplished. In addition to an unspecified number of workers who tended to the machinery in the factory, thirty people were assigned to packing, twenty more to sorting and shipping, and fifteen to keeping accounts (including three stenographers). Products included not only liqueurs but bitters. One hundred thousand liters were stored in the cellar for eventual domestic sale, and exports were sent to France, Denmark, Southwest Africa, and Japan. A cherry press was deemed to be the best in Europe; every day tons of sour cherries were pressed hydraulically. The firm even owned its own small factory for manufacturing seals for its crates.

In addition to being a gifted businessman and manager, Max Kantorowicz was a greatly admired human being. A nephew by marriage, Wilhelm Wolff, reminisced in 1945 about the relative who had died forty-one years earlier: “Max Kantorowicz, what an exemplary man, intellectually sharp and acute, honest and aware of his inner worth, and so simple and modest, and always ready to help others.” Max’s granddaughter, Ellen Fischer, wrote a memoir in which she stated that he was a “liberal democrat, successful businessman, respected citizen and benefactor, city counselor [and] father to his employees in the factory.” Fischer reported that when she lived in New York after the Second World War a Russian lady, visiting her mother on West End Avenue, saw a portrait of Max who she insisted had been a link in an underground chain that smuggled young Jewish men out of Russia at a time of the czarist draft. Fischer supposed that her grandfather gave them money and perhaps a boat ticket before they made their way to America. When Max died “his funeral cortège wound for hours through streets and streets.”

Max’s wife Rosalinde (1854–1916) presided over a household that would have been visited often by the young Ernst Kantorowicz. Wilhelm Wolff described Rosalinde as “lovely, always obliging and cheerful, and dedicated to higher and nobler things.” Ellen Fischer used similar language, calling Rosalinde “sociable, gracious, and lively.” Rosalinde “dressed beautifully (never wore too much jewelry),” had a tasteful salon, and enjoyed playing the piano, especially Chopin. At an advanced age she took delight in playing à quatre mains with a granddaughter. She was one of the muses of the cultural life of Posen. When a student of Richard Wagner came to live in the city, she engaged him to speak in her home about Wagner’s new style of music. A prominent portrait painter, Reinhold Lepsius, spent a month in 1897 in the Kantorowicz house working on a portrait of Rosalinde.

Very little is known about the middle partner, Edmund, who was a bachelor. But one well-documented story serves as compensation. In 1880 Edmund was in Berlin and there became party to a cause célèbre. Bernhard Förster, a high school teacher soon to marry the sister of Friedrich Nietzsche, was a rabid antisemite. On the day Edmund was in town Förster had attended an antisemitic rally in a tavern and was returning home on a horse-drawn tram with some like-minded friends. Fired up from the meeting, Förster continued spouting his rancid opinions, talking loudly of “Jewish impudence,” complaining of “the Jewish press,” mocking Jewish intonations, and warning that Jews would soon be hit by “German blows.” As he spouted he caused a stir, and when he left the tram with his companions another passenger got off as well. According to the language of the subsequent police report, this was a “respected Jewish merchant”—our Edmund Kantorowicz. On the street Förster and the thirty-four-year-old Edmund had words. A crowd gathered and Kantorowicz demanded to know the unruly antisemite’s name. When the reply was, “Why should I tell you? You’re only a Jew,” he responded—again according to the official report—by punching Förster so hard that the latter’s hat fell to the ground. An ensuing melee had to be broken up by the police. The newspapers soon publicized the scuffle and Förster was brought to court. The judge then ruled that he pay a fine and as a teacher in the public schools be placed on probation because of his “unworthy extra-official behavior.”

The third partner was EKa’s father, Joseph. Ellen Fischer wrote that “we children called him ‘uncle Juju’ and loved him.” EKa had a strong bond with Joseph, displayed in exchanges of letters between the two about the political situation right before and during the First World War. In the United States EKa told people that he “loved his father,” unusual language for him, and he kept a photograph of him on his bedroom dresser. A glimpse of the father-son relationship appears in a reminiscence found in a letter of 1961 to Elise Peters, EKa’s favorite relative from the Posen days. He wrote that when he was in his teens he had a brief flirtation with “Clärchen,” the daughter of one of Joseph’s younger brothers. She was very pretty, and, as he could not resist adding, “she wore the most elegant underwear in Berlin.” (He was told this by another female relative Clärchen’s age who had reason to know.) But his father called him into his study (the “Herrenzimmer”) and said, “My son I do not wish that you start anything with Clärchen. Do not forget that she is your first cousin.” EKa recalled that he “was somewhat taken aback by the arbitrary nature of the argument” but decided not to pursue the matter. (At the time he wrote this he was having an affair with another first cousin.)

EKa’s mother, Clara Hepner, was born in 1862 in Jaraczewo, a town of barely a thousand people, thirty-five miles from Posen. The Hepners had drawn on farming to found a large distillery. Joseph probably met Clara in the course of business transactions with the Hepners. Coming from a rural environment, she lacked the sophistication characteristic of...