![]()

CHAPTER 1

FINANCIAL CRASHES: WHAT, HOW, WHY, AND WHEN?

WHAT ARE CRASHES, AND WHY DO WE CARE?

Stock market crashes are momentous financial events that are fascinating to academics and practitioners alike. According to the academic world view that markets are efficient, only the revelation of a dramatic piece of information can cause a crash, yet in reality even the most thorough post-mortem analyses are typically inconclusive as to what this piece of information might have been. For traders and investors, the fear of a crash is a perpetual source of stress, and the onset of the event itself always ruins the lives of some of them.

Most approaches to explaining crashes search for possible mechanisms or effects that operate at very short time scales (hours, days, or weeks at most). This book proposes a radically different view: the underlying cause of the crash will be found in the preceding months and years, in the progressively increasing build-up of market cooperativity, or effective interactions between investors, often translated into accelerating ascent of the market price (the bubble). According to this “critical” point of view, the specific manner by which prices collapsed is not the most important problem: a crash occurs because the market has entered an unstable phase and any small disturbance or process may have triggered the instability. Think of a ruler held up vertically on your finger: this very unstable position will lead eventually to its collapse, as a result of a small (or an absence of adequate) motion of your hand or due to any tiny whiff of air. The collapse is fundamentally due to the unstable position; the instantaneous cause of the collapse is secondary. In the same vein, the growth of the sensitivity and the growing instability of the market close to such a critical point might explain why attempts to unravel the local origin of the crash have been so diverse. Essentially, anything would work once the system is ripe. This book explores the concept that a crash has fundamentally an endogenous, or internal, origin and that exogenous, or external, shocks only serve as triggering factors. As a consequence, the origin of crashes is much more subtle than often thought, as it is constructed progressively by the market as a whole, as a self-organizing process. In this sense, the true cause of a crash could be termed a systemic instability.

Systemic instabilities are of great concern to governments, central banks, and regulatory agencies [103]. The question that often arose in the 1990s was whether the new, globalized, information technology–driven economy had advanced to the point of outgrowing the set of rules dating from the 1950s, in effect creating the need for a new rule set for the “New Economy.” Those who make this call basically point to the systemic instabilities since 1997 (or even back to Mexico’s peso crisis of 1994) as evidence that the old post–World War II rule set is now antiquated, thus condemning this second great period of globalization to the same fate as the first. With the global economy appearing so fragile sometimes, how big a disruption would be needed to throw a wrench into the world’s financial machinery? One of the leading moral authorities, the Basle Committee on Banking Supervision, advised [32] that, “in handling systemic issues, it will be necessary to address, on the one hand, risks to confidence in the financial system and contagion to otherwise sound institutions, and, on the other hand, the need to minimise the distortion to market signals and discipline.”

The dynamics of confidence and of contagion and decision making based on imperfect information are indeed at the core of the book and will lead us to examine the following questions. What are the mechanisms underlying crashes? Can we forecast crashes? Could we control them? Or, at least, could we have some influence on them? Do crashes point to the existence of a fundamental instability in the world financial structure? What could be changed to modify or suppress these instabilities?

THE CRASH OF OCTOBER 1987

From the market opening on October 14, 1987 through the market close on October 19, major indexes of market valuation in the United States declined by 30% or more. Furthermore, all major world markets declined substantially that month, which is itself an exceptional fact that contrasts with the usual modest correlations of returns across countries and the fact that stock markets around the world are amazingly diverse in their organization [30].

In local currency units, the minimum decline was in Austria (−11.4%) and the maximum was in Hong Kong (−45.8%). Out of 23 major industrial countries (Autralia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States), 19 had a decline greater than 20%. Contrary to common belief, the United States was not the first to decline sharply. Non-Japanese Asian markets began a severe decline on October 19, 1987, their time, and this decline was echoed first on a number of European markets, then in North American, and finally in Japan. However, most of the same markets had experienced significant but less severe declines in the latter part of the previous week. With the exception of the United States and Canada, other markets continued downward through the end of October, and some of these declines were as large as the great crash on October 19.

A lot of work has been carried out to unravel the origin(s) of the crash, notably in the properties of trading and the structure of markets; however, no clear cause has been singled out. It is noteworthy that the strong market decline during October 1987 followed what for many countries had been an unprecedented market increase during the first nine months of the year and even before. In the U.S. market, for instance, stock prices advanced 31.4% over those nine months. Some commentators have suggested that the real cause of October’s decline was that overinflated prices generated a speculative bubble during the earlier period.

The main explanations people have come up with are the following.

1. Computer trading. In computer trading, also known as program trading, computers were programmed to automatically order large stock trades when certain market trends prevailed, in particular sell orders after losses. However, during the 1987 U.S. crash, other stock markets that did not use program trading also crashed, some with losses even more severe than the U.S. market.

2. Derivative securities. Index futures and derivative securities have been claimed to increase the variability, risk, and uncertainty of the U.S. stock markets. Nevertheless, none of these techniques or practices existed in previous large, sudden market declines in 1914, 1929, and 1962.

3. Illiquidity. During the crash, the large flow of sell orders could not be digested by the trading mechanisms of existing financial markets. Many common stocks in the New York Stock Exchange were not traded until late in the morning of October 19 because the specialists could not find enough buyers to purchase the amount of stocks that sellers wanted to get rid of at certain prices. This insufficient liquidity may have had a significant effect on the size of the price drop, since investors had overestimated the amount of liquidity. However, negative news about the liquidity of stock markets cannot explain why so many people decided to sell stock at the same time.

4. Trade and budget deficits. The third quarter of 1987 had the largest U.S. trade deficit since 1960, which together with the budget deficit, led investors into thinking that these deficits would cause a fall of the U.S. stocks compared with foreign securities. However, if the large U.S. budget deficit was the cause, why did stock markets in other countries crash as well? Presumably, if unexpected changes in the trade deficit are bad news for one country, they should be good news for its trading partner.

5. Overvaluation. Many analysts agree that stock prices were overvalued in September 1987. While the price/earning ratio and the price/dividend ratio were at historically high levels, similar price/earning and price/dividends values had been seen for most of the 1960–72 period over which no crash occurred. Overvaluation does not seem to trigger crashes every time.

Other cited potential causes involve the auction system itself, the presence or absence of limits on price movements, regulated margin requirements, off-market and off-hours trading (continuous auction and automated quotations), the presence or absence of floor brokers who conduct trades but are not permitted to invest on their own account, the extent of trading in the cash market versus the forward market, the identity of traders (i.e., institutions such as banks or specialized trading firms), the significance of transaction taxes, and other factors.

More rigorous and systematic analyses on univariate associations and multiple regressions of these various factors conclude that it is not at all clear what caused the crash [30]. The most precise statement, albeit somewhat self-referencial, is that the most statistically significant explanatory variable in the October crash can be ascribed to the normal response of each country’s stock market to a worldwide market motion. A world market index was thus constructed [30] by equally weighting the local currency indexes of the 23 major industrial countries mentioned above and normalized to 100 on September 30. It fell to 73.6 by October 30. The important result is that it was found to be statistically related to monthly returns in every country during the period from the beginning of 1981 until the month before the crash, albeit with a wildly varying magnitude of the responses across countries [30]. This correlation was found to swamp the influence of the institutional market characteristics. This signals the possible existence of a subtle but nonetheless influential worldwide cooperativity at times preceding crashes.

HISTORICAL CRASHES

In the financial world, risk, reward, and catastrophe come in irregular cycles witnessed by every generation. Greed, hubris, and systemic fluctuations have given us the tulip mania, the South Sea bubble, the land booms in the 1920s and 1980s, the U.S. stock market and great crash in 1929, and the October 1987 crash, to name just a few of the hundreds of ready examples [454].

THE TULIP MANIA

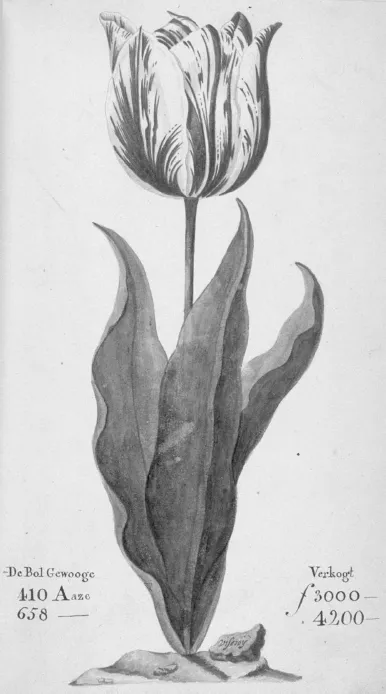

The years of tulip speculation fell within a period of great prosperity in the republic of the Netherlands. Between 1585 and 1650, Amsterdam became the chief commercial emporium, the center of the trade of the northwestern part of Europe, owing to the growing commercial activity in newly discovered America. The tulip as a cultivated flower was imported into western Europe from Turkey and it is first mentioned around 1554. The scarcity of tulips and their beautiful colors made them a must for members of the upper classes of society (see Figure 1.1).

During the build-up of the tulip market, the participants were not making money through the actual process of production. Tulips acted as the medium of speculation and their price determined the wealth of participants in the tulip business. It is not clear whether the build-up attracted new investment or new investment fueled the build-up, or both. What is known is that as the build-up continued, more and more people were roped into investing their hard-won earnings. The price of the tulip lost all correlation to its comparative value with other goods or services.

FIG. 1.1. A variety of tulip (the Viceroy) whose bulb was one of the most expensive at the time of the tulip mania in Amsterdam, from The Tulip Book of P. Cos, including weights and prices from the years of speculative tulip mania (1637); Wageningen UR Library, Special Collections.

What we now call the “tulip mania” of the seventeenth century was the “sure thing” investment during the period from the mid-1500s to 1636. Before its devastating end in 1637, those who bought tulips rarely lost money. People became too confident that this “sure thing” would always make them money and, at the period’s peak, the participants mortgaged their houses and businesses to trade tulips. The craze was so overwhelming that some tulip bulbs of a rare variety sold for the equivalent of a few tens of thousands of dollars. Before the crash, any suggestion that the price of tulips was irrational was dismissed by all the participants.

The conditions now generally associated with the first period of a boom were all present: an increasing currency, a new economy with novel colonial possibilities, and an increasingly prosperous country together had created the optimistic atmosphere in which booms are said to grow.

The crisis came unexpectedly. On February 4, 1637, the possibility of the tulips becoming definitely unsalable was mentioned for the first time. From then until the end of May 1637, all attempts at coordination among florists, bulbgrowers, and the Netherlands were met with failure. Bulbs worth tens of thousands of U.S. dollars (in present value) in early 1637 became valueless a few months later. This remarkable event is often discussed by present-day commentators, and parallels are drawn with modern speculation mania. The question is asked, Do the tulip market’s build-up and its subsequent crash have any relevance for today’s markets?

THE SOUTH SEA BUBBLE

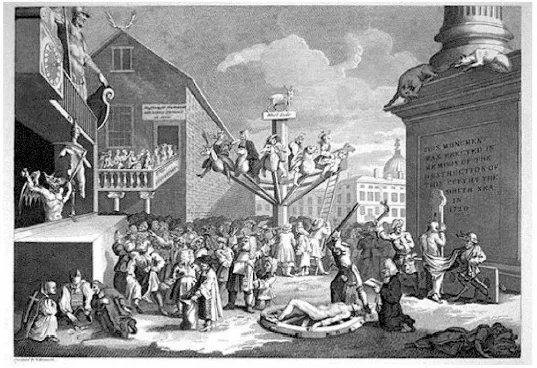

The South Sea bubble is the name given to the enthusiatic speculative fervor that ended in the first great stock market crash in England, in 1720 [454]. The South Sea bubble is a fascinating story of mass hysteria, political corruption, and public upheaval. (See Figure 1.2.) It is really a collection of thousands of stories, tracing the personal fortunes of countless individuals who rode the wave of stock speculation for a furious six months in 1720. The “bubble year,” as it is called, actually involves several individual bubbles, as all kinds of fraudulent joint-stock companies sought to take advantage of the mania for speculation. The following account borrows from “The Bubble Project” [60].

FIG. 1.2. An emblematical print of the South Sea scene (etching and engraving), by the artist William Hogarth in 1722 (now located at The Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University). With this scene, Hogarth satirizes crowds consumed by political speculation on the verge of the stock market collapse of 1720. The “merry-go-round” was set in motion by the South Sea Company, who held a monopoly on trade between ...