![]()

PART ONE

Wandering Languages

FROM CANT TO SLANG

CANT WAS A WANDERING LANGUAGE. It drifted along with the vagrant crews who supposedly spoke it. It made figurative flights from commonly accepted terms or meanings in English. The 1699 New Dictionary of the Terms … of the Canting Crew records the departure of the word “Academy,” for example, from its original meaning to “a bawdy house” and “Joseph” to “a coat or cloak.”1 Cant even wandered away from itself, its lexicon constantly renewed with the addition of terms. The 1725 New Canting Academy adds “Bingo-Mort, a female drunkard” and “Black Mouth, foul malicious railing” to the cant vocabulary, while Francis Grose’s 1785 collection inserts “Black Art, The art of picking a lock.”2 Sometimes this strange language lost its verbal meaning altogether. In the early seventeenth century Thomas Dekker described its status as pure sound: “the language of canting is a kinde of musicke, and he that in such assemblies can cant best, is counted the best Musitian [sic].”3 In the course of the eighteenth century, it wandered in its social meaning, too. At the beginning of the century, lexicographers and writers warned against cant as a coded thieves’ language. They drew from publications nearly as old as English print itself that had depicted it as an alien argot shrouding the criminal activities of itinerant hostile bands targeting the good people of England.4 By 1785, however, alongside these dictionaries appeared Grose’s endlessly reproduced A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, which classifies cant with the homegrown “vulgar” language of the “common people,” representative of Britain’s demotic and lively—because uniquely free—national tongue.5 A wandering language comes to form one basis of the “vulgar” tongue, a strange vernacular of a nation composed (as they all are, after all) of strangers.

The following four chapters track the eighteenth-century’s startling reclamation of cant: of terms such as “dudds” (clothes), “pinch” (steal), and “clodhopper” (a ploughman), once believed to be the exclusive and secret language of criminals, as part of the furtively prized vernacular of the British “common people.”6 While Julie Coleman has described the process by which slang words are sometimes incorporated into standard English, the interest in these chapters is specifically representations of the cant language associated with criminals and its odd metamorphosis, in those representations, into a sign of Britishness itself.7 Why, for instance, do print collections come to situate colloquial terms and proverbs alongside cant terms? What ideas about language and “the people”—particularly notions of a freeborn English people—allowed the wandering language of cant to make itself a home of sorts in the English lexicon? What role did emerging genres, from novels and vernacular dictionaries to comic operas, play in ushering in new ways of imagining a national language? And how did the lingering residue of wandering criminality, of an alien presence in the nation’s midst, taint notions of “common” language and the people who spoke it? The following chapters will show cant to be a strange double for a national vernacular more generally, especially in its continuous movement, its wandering between strangeness and familiarity, between opacity and transparency, between being readers’ own and not. If, as a number of critics have recently noted, the modern nation demands negotiations with strangers, considering those negotiations at the level of language reveals just how early, and how complex, they were.

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Reappraising Cant

“CATERPILLARS” AND SLAVES

“Caterpillars”: Cant and the Threat to the Commonwealth

In the eighteenth century, as realist fiction, vernacular dictionaries, and other print institutions that helped establish a national language took shape, criminal cant terms began to appear alongside a more quotidian if lowly set of terms associated with a common English vernacular. Before examining that shift, it is worth considering pre-eighteenth-century depictions of cant to understand just how unusual that coappearance was and what associations cant brought with it in its eighteenth-century representations. Here I should say that I limit discussion primarily to print representations and the work they do, rather than attempting to make claims about an actual cant language and its speakers. These early works, with their depictions of nefarious, incomprehensible criminals, have much more to tell us about the society that produced those works than about some vague, largely invented criminal element that might or might not have spoken it.1 Eighteenth-century representations of cant, as we shall see, retained that sense of the language’s waywardness, its exciting danger, while folding it into the idea of a vernacular that could familiarize strangers.

The authors of many fifteenth- through seventeenth-century booklets claimed to have discovered a secret language that named the various orders of clandestine miscreants, their crimes, and their methods of “conny-catching” (cheating the unwary, figured as hapless rabbits, or coneys).2 According to these works, as marginal figures such as rogues, vagabonds, thieves, and prostitutes ranged through the British Isles, they spoke to each other in cant, which one writer referred to as “their native language.”3 In print representations, this imputed language served as their distinguishing trait, and these groups were known as “canting crews.”4 According to Robert Greene’s 1592 Groundworke of Conny-Catching, their neologisms named not only the illicit, such as “stauling ken,” meaning “a house that will receive stolen wares,” but also the licit, such as “autem,” meaning church, and “nab,” meaning head.5 Similarly, nearly one hundred years later, the list of cant terms included in Richard Head’s 1673 Canting Academy features not only words related to crime (such as “bite” for “to cheat or cozen” and “fencing cully” for “receiver of stolen goods”) but also strange-sounding words for the most common of things and qualities, such as “fambles,” meaning “hands,” “cove,” meaning “a man,” and “dimber,” meaning “pretty.”6 Print representations depicted this coded language and its unintelligibility to others as the property of a discrete, wandering community with a wholly separate way of life. In such depictions, cant is conditionally intelligible, traded between canters, and strategically excludes “upstanding” Britons.

While terms such as “dimber” and “fambles” pose an alien language, other cant terms such as “bite” (cheat) and “fence” (“a receiver … of stolen goods”) innovate on English itself, giving new meanings that any speaker willing to think metaphorically might follow (“bite” and the aggression of and pain in being cheated; “fence” in “legitimate” English at this time also meaning to evade a question or to screen or shield). The movement back and forth between alien, unrecognizable words and familiar (if somewhat also defamiliarized) English provides glimmering recognition of the fact that cant and the vernacular might be secret sharers, their proximity increasingly visible in eighteenth-century glossaries that combine riddlelike proverbs and cant terms. The wavering between unknown and familiar language, between non-meaning and meaning, was part of the draw for contemporary readers and would come to characterize, too, vernacular language as at once strange and one’s own.

Many sixteenth and seventeenth-century depictions of cant, however, represent it as primarily a strange tongue spoken by isolated, suspect “tribes,” its wandering, essentially foreign nature marked by one of its earliest names—“peddlers’ French”—its speakers sometimes designated as foreigners—Egyptians.7 Thomas Dekker holds that “as these people are strange both in names and in their condition, so doe they speake a language called canting which is more strange.”8 Early writers, moreover, believed strict borders between cant and English could and should be maintained. In his print lists of terms, rural sheriff Thomas Harman, who collected, translated, and published cant in the sixteenth century, insists he is “not meaning to English the same” (although that was exactly what he was doing, for “to English” also meant, suggestively, to translate).9 Decidedly moralistic in his approach, Harman reviles the “unlawful language” of cant and couples it with immoral criminal roving as the language of “pilfering, wiley wandering and … lechery.”10 Thomas Dekker calls canters “wild men” and “savages.”11 Canters, these works resolutely declare, are not us, their wandering language not ours. This, despite the fact that, as Jeffrey Knapp has argued, many had seen the Reformation as having made the English themselves wanderers from the unity and stability of the Catholic Church. In this scenario, rogue cant speakers were both a sign and a displacement of England’s own disruptions of “traditional notions of community.”12

For Dekker, however, cant’s apparent incoherence is also a lingering reminder of the confusion of Babel and the fallen status of all humans and all languages, a metonym of failure and pernicious linguistic difference that has become part of the condition of language across space. A world in which cant is spoken contrasts the pre-Babel time Dekker describes:

When all the World was but one Kingdome, all the People in that Kingdome spake but one Language. A man could travel in those dayes neyther by Sea nor land, but he met his Countreymen & none others. Two could not then stand gabling with strange tongues, and conspire together (to his owne face) how to cut a third mans throate13

This time offered an ontologically distinct sense of language, for in a post-Babel state, as Daniel Heller-Roazen has put it, “speaking subjects speak only languages, and their basic element is opacity.”14 Post-Babel unintelligibility is a reminder of the history of human sinfulness, pride, and consequent fall. Whether due to national linguistic difference or the difference within a national language between cant and “legitimate” language, it also contains within it the potential for violence. If, in some accounts, writing and the difference between literate and illiterate suggests this—recall the illiterate messenger who unknowingly carries the written orders for his own execution—for Dekker that potential is relocated to linguistic difference itself, in people “gabling with strange tongues” who are conspiring “how to cut a third mans throate.” Dekker uses cant as a figure for the violence he sees in a fallen world of linguistic difference. And wandering poses dangerous encounters with strangers and their strange languages.

Dekker and others believed that cant, despite its efficacy for conspiratorial use, was also disordered, a reflection of the chaos of Babel itself. Of the latter, he writes, “Their tongues went … yet neyther words nor action were understood. It was a noise of a thousand sounds, and yet the sound of the noise was nothing.” This description is resonant with his characterization of cant-speakers, among whom “confusion never dwelt more amongst any creatures,” and of their language: “I see not that it is grounded on any certaine rules.” (He added that it was marked by “irregularity…. [and] within less then foure-scoure yeares not a word of this language was knowen.”15) Cant was a return to—or reemergence of—the sound without meaning—noise—that was Babel, a language in which tongues go, but “neyther words nor action [are] understood.” Richard Head, a hack writing many decades after Harman and Dekker, and less morally outraged by canters than were his predecessors, nonetheless also describes canters’ delinquent language as a “speech as confused as the professors thereof are disorderly disposed.”16 In these descriptions, cant is mere “noise,” its non-meaning suggesting violence and lawlessness. Such characterizations remind us that language might constitute community through two models, one of similitude and inclusion, in which two speakers share a language, but another of difference and exclusion, in which an excluded third and his or her noise, in this case cant, must exist and must be canceled out (52).17

Cant’s break between sound and meaning was, in Harman’s, Dekker’s, and Head’s texts, at once morally objectionable and also the basis of its allure. Their works promised revelations, no doubt beguiling readers with the hopes of disclosure of the unknown—seemingly unknowable—and forbidden. Head entices with the pledge of his Canting Academy, or, the Devils Cabinet Broke Open to expose “the mysterious and villainous practices of that wicked crew.”18 Here the lingo of these sneaking aliens, rather than conveying no sense, bespeaks edgy lives and outlaw acts hidden in stubbornly locked cabinets and the dark spaces into which a lantern might cast a brief illumination, as described in the quasi-gothic title (and preface) of Dekker’s Lanthorne and Candle-light. The rhetoric of inscrutability transforms into that of partial revelation in these works, as they hold out the prospect that in their pages lurid and chaotic cant terms, generally hidden from daily life, might be flickeringly exposed. The noise on occasion might be rendered meaningful—but that meaning signals danger.

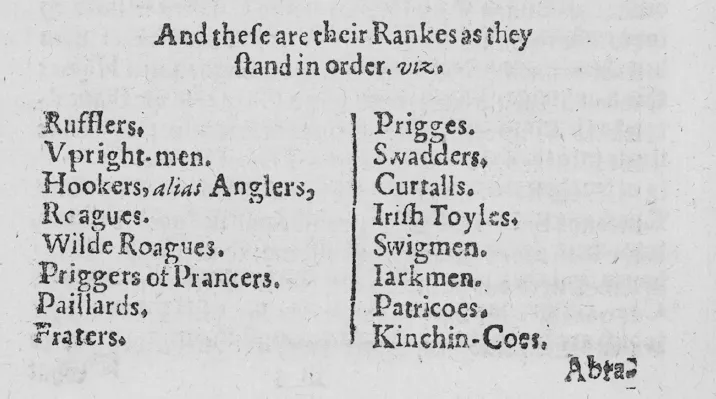

Like later gothic literature, these early print representations of cant often played on aural sensation and its occulted meaning. Print on the page conjures the aural, either the unclear meaning of strange sounds or possibly malevolent unknown words producing sensation. Dekker’s printed cant conjures sound in the reduction of words on the page to acoustic experience, their meaning unknown. The author provides an untranslated list of terms early in his book:

Rufflers.

…

Hookers, alias Anglers.

…

Priggers of Prancers.

Palliards.

Fraters.

…

Prigges.

Swadders.19

Any English reader could pronounce these sequences of phonemes, but the sounds, for most, would be empty of meaning, though saturated with the ominous connection to conspiring criminals. In Dekker’s book these terms then appear in printed rhyme and song lines, where sound—in acoustic patterns—is further emphasized above meaning. Dekker urges his reader to “stay and heare a Canter in his owne language” (my emphasis) and offers what he calls “Canting Rithmes”: “Enough—with bowsy Cove maund Nace, / Tour the Patring Cove in the Darkeman Case.”20 The lines had appeared years earlier in Robert Copland’s The Hye Way to the Spittal Hous.21 Dekker’s sense of mystery, however, was not yet a part of that earlier representation. Copland’s verse dialogue between a traveler and the porter of a charity house enumerated the various deserving and undeserving poor who sought shelter at the “Spittal Hous,” among them the peddler whose language the porter briefly imitates. The language of this supplicant is not especially dangerous or mysterious. And, while Dekker and Harman would later suggest that cant-speakers were so alien as to be from beyond the shores of England, none of the petitioners in Copland’s work, worthy and unworthy, are from outside England. His peddler, although a wanderer, poses no threat.22

FIGURE 2: From Thomas Dekker, Lanthorne and Candle-Light (London, 1608). C.27.b.27, folio 7, verso. The British Libra...