![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

THE ESTRANGEMENT OF CREATION, PRODUCTION, AND RECEPTION

A NOVEL MUST BE MANY THINGS

Of the thousands of novels that were published in the United States at around the same time, Jarrettsville was one of the very few that ended up on the front tables of bookstores around the country, although the novel’s publisher, Counterpoint Press, eventually regretted that. Of the thousands of novels released around the same time, Jarrettsville was also one of the very few that was reviewed in the New York Times, although perhaps Counterpoint eventually regretted that too. Yet Jarrettsville sold reasonably well. Jarrettsville was, in the words of Counterpoint’s CEO Charlie Winton, “a typical publishing story.” According to Winton, a typical publishing story ends like this: “Well, that was good, sort of.”

For Jarrettsville’s author, Cornelia Nixon, the story that would become “good, sort of” to her publisher had first been a family secret. The gist of the once-secret story revealed in Nixon’s novel was that following the Civil War, just south of the Mason-Dixon line in Jarrettsville, Maryland, one of Nixon’s ancestors, Martha Jane Cairnes, shot and killed her newborn baby’s father, Nicholas McComas, in front of about fifty eyewitnesses during a parade celebrating the Confederate surrender. Despite all those witnesses, and even her own admission of guilt, a jury of her peers found Cairnes innocent on the ad hoc grounds of “justifiable homicide.” The story had been front-page news in the New York Times before it was lost to history.

As a novelist, Cornelia Nixon took this family story and transformed it into a work of historical fiction. Or maybe Jarrettsville was better described as a work of popular fiction, or literary fiction, or something in between; while writing the novel Nixon was hoping it might garner a wider audience of readers to match all of her literary awards. Or, perhaps Nixon had transformed her family story into somewhat of a romance novel or, for her publisher, maybe just a bit too much of a romance novel. For Winton, Nixon’s novel was reminiscent of Cold Mountain, an investment in a second chance at catching lightning in a bottle. For Adam Krefman, Jarrettsville’s editor at Counterpoint, the novel was an intimate examination of a one-time secondary character’s failings, his inability to do the right thing, and the mistakes made by young men that young men like Krefman might understand. For Counterpoint’s publicity staff, and for the field reps at Counterpoint’s distributor, Jarrettsville was a work of literary historical fiction. It was “literary” because both Nixon and Counterpoint were “literary,” and it was historical fiction not only because the story was historical and a work of fiction, but also because “historical fiction” existed as a market category. Importantly for Counterpoint, Jarrettsville was not just historical fiction, but it was Civil War historical fiction, a profitable and perhaps even dependable market category. That none of the novel actually took place during the Civil War was treated by all involved as mostly incidental. If “postbellum fiction” had existed as a recognizable market category, perhaps Jarrettsville would have been that, but it didn’t, so Civil War fiction it became.

For reviewers, Jarrettsville was about the inescapability of racism in the United States, or the lingering tensions of the Civil War, or not really either of those things as it was instead a timeless morality tale about the characters. For one reviewer, Jarrettsville was an exquisite story about social conventions, emotional connections, and the human experience, reminiscent of Tolstoy and worth reading for the impressive quality of the writing alone. For a different reviewer, Jarrettsville was a failed effort rife with historical inaccuracies, with writing so bad it was “timeless.” For a book group of women in Nashville, Tennessee, Jarrettsville was compared to what they jokingly referred to as “the sacred text,” Gone with the Wind. For a book group of men in Massachusetts, the prose was too flowery, but the plot offered an opportunity to discuss if a woman can rape a man. For a group of teachers in Southern California, Jarrettsville was an entry point into its readers’ own stories about racism in America. For a group of lawyers and their friends in Northern California, it was about whether juries can break from a judge’s guidelines in meting out convictions and acquittals. “Is ‘justifiable homicide’ something that a jury can use? Doesn’t that seem crazy?” a poet asked. “It’s rare, but juries can do whatever they want,” a lawyer replied.

For readers in present-day Jarrettsville, Maryland, the story was about much more than long-dead people from a bygone time. The story was also about them. Over the past hundred thirty years, had Jarrettsville changed, or was it still like Jarrettsville? Some things had remained the same. In the new Jarrettsville branch of the Harford County Library, which sits across the street from a rolling field of sunflowers which is both idyllically pastoral and an investment in bird feed as a cash crop, the first question of the morning book club was a difficult one that set the terms of the discussion: were its members, as residents of Jarrettsville and readers of Jarrettsville, Northerners or Southerners?

Although Jarrettsville would go on to be many different things for different people, for Cornelia Nixon, at first at least, it was just a family story. For a story to become a novel—for it to be written by an author, make it through a literary agency, get into a publishing house and out the other end, be promoted by publicity staff, be hand-sold in bookstores, be evaluated by reviewers and ultimately connected with by readers—it must be multiple. To ultimately be a novel, Jarrettsville had to be many things.

Jarrettsville was a personal story, a work of fiction, a work of Civil War historical fiction, a salable commodity, and a chance to reboot a career. At the same time it was an opportunity to reactivate embedded social ties within an industry around a new product, a text that had to be read before a meeting, a leisure activity, and a break from life that was “perfect cross-country flight” length. It was a story that was really about a relationship between a mother and a daughter, and a story that was, according to two women on opposite sides of the country who had never met and who were both ultimately dissuaded from this interpretation, really about the US occupation of Iraq. Jarrettsville was also contract work for a moonlighting copy editor, a chance to flex a different muscle for the cover designer of travel books, and the day job of an editor-in-chief. For a novel to be a novel it must pass through the hands of many people who have many different orientations to novels and who occupy different locations and milieus. In order for it to continue passing through those hands and still be meaningful and worthy of passing on, Jarrettsville had to change too. This book is a collection of all of the stories of what Jarrettsville was, and how it came to be all of those things at once.

This book is also an academic work of sociology, and hopefully one with some of its more inscrutable edges smoothed off. If you are not a sociologist (amateur, budding, or full-blown), the next three sections of this introduction (before the final one) are about those more inscrutable edges. If you just want the story of how a novel was created, produced, and consumed, feel free to skip them. All you need to know is that they describe how sociologists came to an arrangement about how to study things like Jarrettsville, and how this book offers a different and more integrative path. If you don’t care about that sociological theorizing, this book still has a narrative arc built into it, complete with a clearly defined beginning, middle, and end. For sociologists this three-act structure is a story about three interdependent fields, whereas for non-sociologists it’s just a three-act structure, a pretty good way to tell a story.

THE SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY OF THINGS THAT ARE MANY THINGS

Novels travel, through hands and across place and time, and in and out of different fields occupied by people with different orientations, experiences, needs, constraints, expectations, and preferences. Yet in making sense of cultural objects such as Jarrettsville, subjects of analysis have been cordoned off into discrete terrains. While some focus on the value of cultural objects, others study their values. While some study the objects themselves, others consciously avoid the object, and instead focus on either the industries from which they emerge or the communities of consumers into which they pass. When studying cultural objects such as novels, equations have been simplified through the construction of disciplinary-dependent binaries: when talking novels, are we talking about art or commerce, production or reception, creativity or constraint, the making of meaning or the extraction of value?

Because different elements of cultural objects have been split apart across disciplines and subfields, it is not just harder to make sense of their multiplicity, but it is also harder to make sense of them as wholes. Once you have entirely bracketed out the twists and turns of a novel’s creation, it’s hard, if not impossible, to fully understand what an editor or marketing rep are doing as they balance the text they’re working on with the context they’re working under. For cultural reception, a novel can be treated as being of infinitely variable meanings only if all the years of work by an author and publisher to make it meaningful at all have also been bracketed out as an “unobservable” prehistory to reader engagement. If creation, production, and reception all matter, what is lost by independently studying these processes and the transitions between them is actually most things.

As a result of this arrangement, to make sense of a novel by describing only its authoring can be like trying to describe an elephant by describing only its ear. So too can describing a novel by describing only its production be like describing an elephant by describing only its trunk. Maybe the reception of a novel in the metaphor is an elephant’s legs: another important component in the description of an elephant, but still not the elephant.1 There are no shortages of things to learn and know when specializing in ears, trunks, or legs—and thankfully for us, there are cardiologists, neurologists, and oncologists who specialize in this way—but if the goal is to really understand an elephant, descriptions of its individual body parts must be brought back together in order to describe the whole. Following the creation, production, and reception of a novel from start to finish is how this book goes about doing that.

THE ESTRANGEMENT OF PRODUCTION FROM RECEPTION IN SOCIOLOGY

From the early twentieth century through the beginning of the 1970s, the sociological analysis of cultural objects took one of two competing paths, which interestingly shared a core assumption. The products of mediated culture, whether books, songs, or fashion, were thought to be expressive symbols that changed in lockstep with evolutions in society. For example, in 1919 the anthropologist Alfred Kroeber argued that the hemlines of women’s dresses were prescribed through “civilizational determinism”; they were a window into macro-level cultural values and belief systems.2 In turn, by the mid-1920s the economist George Taylor argued that instead the hemlines of dresses go up with rises and go down with declines in the stock market.3 For Taylor, hemlines were determined by macro-level economic, not cultural, shifts. While these “nothing-but” arguments quibbled on the direction of the association between culture and the economy, they both assumed that hemline lengths in women’s fashion were reflections of outsized societal forces.4 Such was also the case with the sociological understanding of cultural objects as reflective of either a more abstract Parsonian values system, or a less abstract capitalist system within a Marxist framework.5 In both accounts, the production and reception of culture were conjoined and determined by outside forces.6

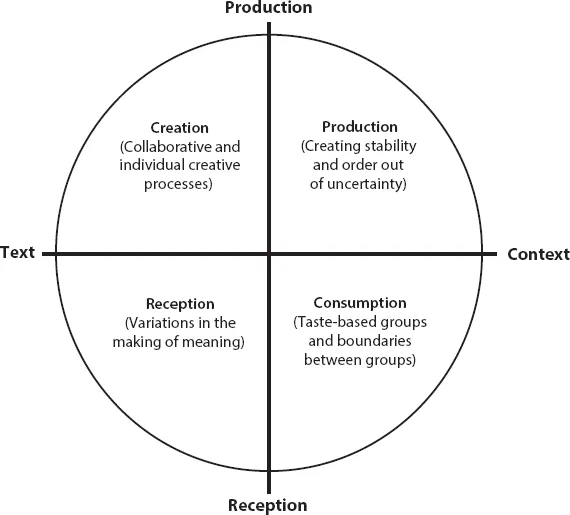

In reaction to both of these macro-level functionalist theories of culture, starting in the 1970s, the sociological study of production and reception split. Scholars of production, like scholars of reception, scaled down from grand narratives into thinking of culture and structure as “elements in an ever changing patchwork.”7 Like all patchworks, the details of one piece may tell you very little about the details of another. Such was also the case with production and reception, it seemed. Production-oriented scholars noted that changes in popular culture are generally asynchronous with bigger transformations in society; hemlines change because of what’s happening in the fashion industry, not because of the stock market or broader shifts in values.8 For reception-oriented scholars, how people actually made sense of things like hemlines and what they did with them proved to be much more interesting than the theories we had saddled onto them. For both production and reception scholars, once they pried open the black box of assumed values or ideological intentions, it turned out there were real people inside, working within systems of conventions and constraints in the case of production, or to foster identities and senses of meaning in the case of reception.9 Yet over time, as this split between the studies of production and reception widened, rather than having grouped into competing teams, scholars of each area had basically resigned themselves to playing entirely different sports (see Figure 1.1).10

FIGURE 1.1: The Friendly Divvying Up of Material Culture.

Production-oriented scholars focused on the specific contexts of production, investigating how order and stability were created in the construction of one-off cultural goods for which audience demand was unpredictable.11 The culture that was produced was, in effect, conditioned on the circumstances in the industries in which it was created.12 As cultural objects were the “outcomes” of industry conditions, their meanings became dependent variables, which was part of a self-conscious research posit...