![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

EMPIRE CONSUMED AMERICANS in the nation’s earliest years, as an idea, an aspiration, and a reality. The colonists declared their independence from Britain, were surrounded by France and Spain, and frequently spoke of the glory of Rome, as they looked north, south, and west at vast expanses of land. Although the word “empire” meant different things to different people, it was used widely and ambitiously. George Washington predicted “there will assuredly come a day, when this country will have some weight in the scale of Empires,” while Alexander Hamilton wrote in the first of the Federalist Papers of “the fate of an empire, in many respects, the most interesting in the world.” Some, like Thomas Jefferson, thought the United States would quickly expand over the northern and southern hemisphere, providing “an empire of liberty” of which “no constitution was ever before so well calculated as ours for extensive empire and self government.”1

These aspirations were quickly acted upon. Political dynamism, population movement, land acquisition, and racial imperialism dominated the early development of the American nation. In the first half of the nineteenth century, the United States expanded from thirteen states along the Atlantic seaboard west to the Pacific Ocean and south to the Rio Grande. Most notably, with the Louisiana Purchase, the nation nearly doubled in size, acquiring land that stretched from New Orleans over the Great Plains to the Canadian border. Decades later, Texas Annexation and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo provided the United States with more than half of Mexico’s existing territory, further stretching the nation west to the Pacific. By the mid-nineteenth century, after further transactions with British, Spanish, and Mexican officials, the United States had acquired more than 2.2 million square acres of land on which it eventually established twenty-two new states (figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1. U.S. territorial expansion in the Antebellum Era. Adapted from http://nationalmap.gov/small_scale/printable/territorialacquisition.html#list. Map services and data available from U.S. Geological Survey, National Geospatial Program.

From the perspective of the early twenty-first century, the representation of territorial expansion in figure 1.1 is both familiar and natural, a reflection of a long-established American nation-state seemingly destined to be situated between sea and shining sea. But the map is misleading. It truncates and flattens a lengthy, diverse, and contested project of national state formation, a project that evolved not so much linearly but rather in fits and starts, with successes and failures, and in quite varied geographic, demographic, political, and institutional contexts.

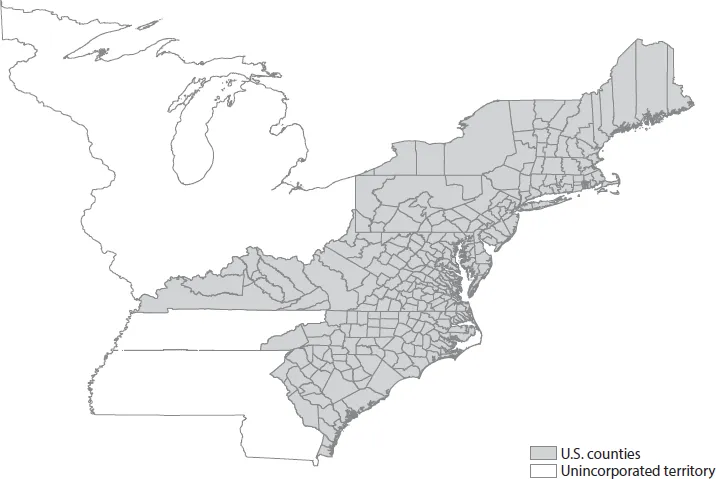

To get an initial sense of the contested and multifaceted nature of the expansionist project, compare the territorial boundary line in the middle of figure 1.1 that identifies the initial borders of the United States as set by the Treaty of Paris in 1783 with the map in figure 1.2 of U.S. incorporated counties in 1790. What immediately distinguishes the two figures is that the first represents the sovereign authority the nation asserted over the land to the Mississippi River, while the second illuminates the considerable portion of the land that was unincorporated and largely unpopulated by American citizens. This land was not simply empty, of course, waiting invitingly for the arrival of American settlers. Rather, hundreds of thousands of people indigenous to the continent lived on and were recognized as having property rights in the land. Although the population of Native Americans east of the Mississippi was smaller than that of the early American nation, it was not exceedingly so; only by the middle of the eighteenth century—just a few decades prior to the Treaty of Paris—had the balance of populations shifted decisively between European colonizers and indigenous people, and this was certainly not the case the farther west one traveled.2 Moreover, American statesmen at the time feared Indian nations with fighting forces thought to far outnumber those of the United States, militaries that were further empowered by the alliances many of these nations had with hovering European empires seeking to maintain their own political foundations on the continent. A “middle ground,” as Richard White has famously termed the negotiated relationships between indigenous populations and colonizers at the time, stood in the way of American hegemony.3

FIGURE 1.2. U.S. incorporation in 1790 (map of U.S. counties). Adapted from Minnesota Population Center, National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 2.0 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2011), http://www.nhgis.org.

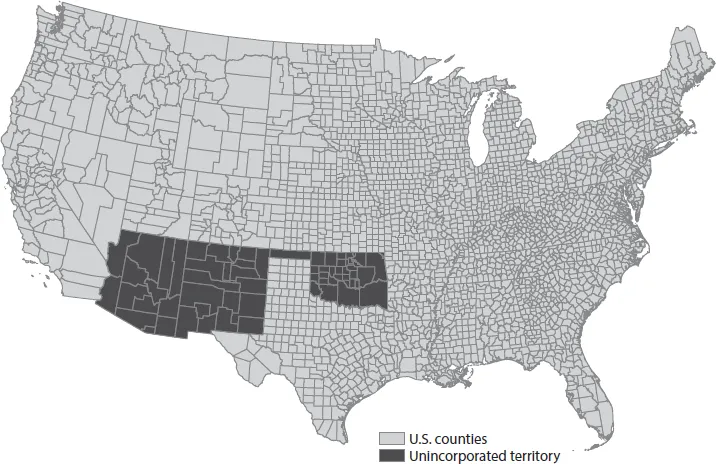

FIGURE 1.3. U.S. incorporation in 1900 (map of U.S. counties). Adapted from Minnesota Population Center, National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 2.0 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2011), http://www.nhgis.org.

Having not been parties to the Treaty of Paris, Native American nations contested the United States’ assertion of sovereignty, necessitating that American political leaders engage in a second process of land acquisition in the western territories. American government officials at the time often referred to this process as a “quieting”; but it involved not just treaties and land purchases, but also consistent violence. The final years of the nation’s incorporation of the land granted by the Treaty of Paris in particular were marked by what current-day international law defines as genocide, with the coerced resettlement of nearly one hundred thousand Native Americans in the 1830s and with deaths estimated in the many thousands. Only in the 1850s did the United States fully incorporate the lands within its 1783 borders with a series of settlements and the establishment of new states that covered all the land east of the Mississippi River.

Similar issues with the incorporation of territorial peripheries took place west of the Mississippi. Figure 1.3 provides a map of U.S. incorporated counties at the turn of the twentieth century. By 1900, the United States had certainly advanced far beyond its 1783 borders, had fought a civil war to end slavery and diminish regional antagonisms, and was in the process of building a massive industrial empire. Further, the nation had overcome the “middle grounds” of the latter half of the nineteenth century, such as its engagements with the Sioux on the Great Plains and the Comanche in the southwest.4 But even by the start of the twentieth century, a large swath of land remained unincorporated territory—specifically, the territory that became the state of Oklahoma in 1907, and that which became Arizona and New Mexico in 1912.

The state of Oklahoma’s borders were drawn from the remaining land of Indian Territory, first formed in the midst of Indian removal policies beginning in the 1820s in order to provide a long-term place for those indigenous populations forced from their homes east of the Mississippi. In subsequent years, many other Indian nations joined them, having been forcibly removed from their homes that stretched from the Dakotas to the Pacific Ocean. The size of Indian Territory shrunk rapidly over the course of the nineteenth century, with the establishment of states and railroad lines carving away Indian property from all sides.5 At the end of the century, the Dawes Act took yet more land away from Native Americans in the territory, land that the U.S. government quickly opened up to American settlement. More than one million people moved to Oklahoma in little more than a decade, and statehood was established shortly after. Arizona and New Mexico, meanwhile, had stalled in their move toward statehood because they too were home to large numbers of indigenous populations that remained stalwart in resisting the United States. They were also home to a significant Mexican population, most of whom dated their residence in the territory back to the days of the Spanish empire. Here again, the diversity of these territories created significant obstacles for American state builders, who were stymied both by guerilla warfare and by domestic opposition to the prospect of incorporating communities with different languages, races, and religions. After Congress repeatedly rejected statehood for the two territories, a surge of white settlers into the region at the turn of the century marked the completion of U.S. incorporation of the contiguous forty-eight states.

Finally, compare figure 1.1 with figure 1.4. Many political leaders spoke of extending national borders much farther, claiming a “manifest destiny” that might someday eventuate in the nation’s capital resting in Mexico City or even Rio de Janeiro. Figure 1.4 is a map of lands that the United States seriously debated annexing, but ultimately chose not to. By “seriously,” I mean that the decision was made after significant and closely fought congressional and executive battles. By “chose not to do so,” I mean that, regardless of whether these lands wished to join the United States, American political leaders thought they might, and legislators acted to prevent against the possibility of annexation. In short, these are lands that U.S. politicians believed were available for acquisition had there been a majority of legislators willing to say “yes” to expansion. But in critical moments when these lands were thought to be available, a majority of legislators ultimately said “no.” These areas include the island of Cuba, so geographically close to the U.S. borders that many believed it a natural appendage to the continental empire. Thomas Jefferson referred to Cuba as “the most interesting addition which could ever be made to our system of States,” and John Quincy Adams called the island “an object of transcendent importance,” with its annexation “indispensable to the continuance and integrity of the Union itself.”6 Many in the South viewed the annexation of Cuba as absolutely vital to maintaining the balance in Congress between slave and abolitionist interests and to maintaining their own economic interests in the Caribbean.7 Other areas rejected by national governing officials include the Dominican Republic, extensive swaths of land in Mexico, and other nations south of the U.S. border that at different times American statesmen believed were necessary to the nation for strategic, political, or economic reasons, or simply as fulfillments of grandeur.8

The imperial aspirations and geographic expansion of the United States over the long nineteenth century represent one of the nation’s earliest and most foundational political projects. But few scholars interested in American state formation and political development have paid much attention to the process, leaving conventional explanations for why the United States expanded at the rate and scale that it did, where it expanded, as well as where it ultimately did not expand, to remain rooted in exceptional and largely apolitical terms. The scale and speed of territorial acquisition suggests that the process of border establishment was easy, a result of fluid geography, germs, divinity, and luck more so than the authoritative assertion of a nation-state. As Alexis de Tocqueville famously wrote, “Fortune, which has showered so many peculiar favors on the inhabitants of the United States, has placed them in the midst of a wilderness where one can almost say that they have no neighbors. For them a few thousand soldiers are enough.”9

FIGURE 1.4. Alternative map of nineteenth-century U.S. expansion.

The preceding three figures illuminate something very different from Tocqueville’s sanguine vision. First, territorial expansion necessarily involved constant confrontations between the United States and the people who already lived on the land. Most notably, the United States confronted many hundreds of thousands of people indigenous to the land: roughly 600,000 by the federal government’s own estimation. The United States further confronted roughly 50,000 French and Caribbean settlers in Louisiana, as well as thousands of free blacks and far larger numbers of African slaves; more than 100,000 Mexican citizens and indigenous populations living in the Southwest; potentially more than half a million people in Cuba; millions in Mexico; and hundreds of thousands of others, many of mixed race and ancestry, in a multitude of locations.

All of these meetings of peoples—sometimes “engagements,” but more often “confrontations”—forced the nation to make decisions about how they imagined the evolving national community.10 The dynamic nature of expansion continually prompted debate in the United States regarding how various populations might or might not fit into broader questions of sovereignty, democracy, and community. Expansion forced everyone from aspiring empire builders, settlers, and people indigenous to the land to reevaluate and frequently adapt their own ideologies and identities.11 The most common decision by the federal government was to maintain the project of territorial expansion and forcibly remove indigenous populations in the way. But removal policies were not the only option, and were contested in both the domestic and international context by those proposing a wide range of alternatives. In some moments and places, Americans supported incorporating as citizens the populations they confronted. Other Americans and many Native American leaders endorsed cohabitation on the land as separate national entities. At still other times, government officials opposed further expansion, especially when acquiring new lands meant having to incorporate nonwhite populations into the national polity, deciding instead to leave certain populations on the other side of the territorial border.

Second, the federal government played a critical role in weighing these choices about a national community and in manufacturing the establishment and incorporation of the nation’s final borders. The government signed hundreds of treaties with Native Americans and raised militia to win wars. But the government’s role was not just as a nation-state conquering territory through the familiar international process of war and treaty; federal officials were also domestic policy makers regulating the process of securing and incorporating disputed territory, people, and property on the nation’s frontier. In particular, the government regulated the task of settlement by controlling its direction, pace, and scale—moving preferred populations onto contested territory in order to engineer the demography of the region in a manner that both secured and consolidated their territorial control.

Very early on in the nation’s history, the federal government asserted legal title over all the land that it acquired in its treaties with other sovereign nations. This was not an obvious power of the government at the time—individual states, people who had settled on the land, economic entrepreneurs, and rival peoples and nations all contested U.S. rights to ownership. In declaring a monopoly over the land, the federal government asserted the authority to regulate the sale and distribution of property over the vast geographic territory that was larger than that of the existing thirteen states. This gave the government a potential economic resource through land sales. It also allowed the government to control the movement of people and settlement patterns. The government regulated the public land so as to lure immigrants to the United States, to control the pace and direction with which settlers moved west, and to maintain strategic proxi...