![]()

PART 1

Mechanisms

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Mate Choice and Mating Preferences

AN OVERVIEW

1.1 INTRODUCTION

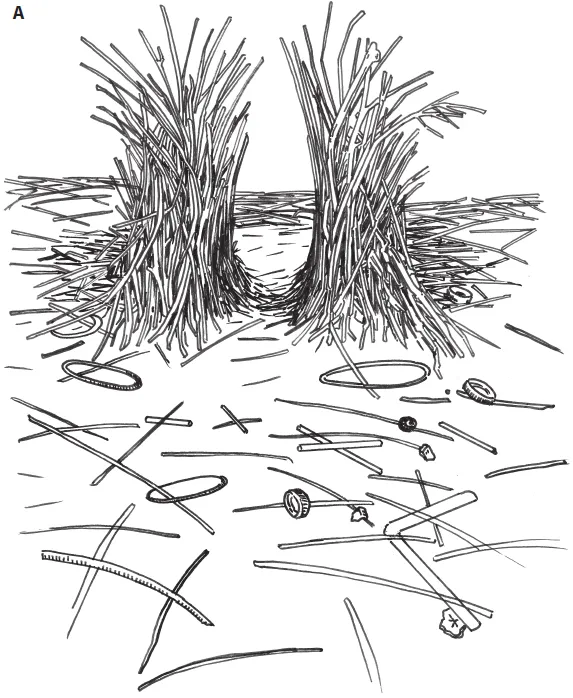

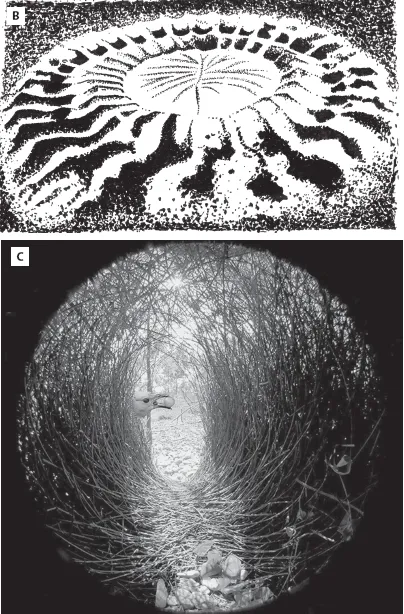

Hiking in the eucalyptus woods of northern Australia, we might come upon an odd structure with a promenade of shells and bones leading up to a curving, symmetric arch. We might reasonably speculate that we have stumbled upon an indigenous ceremonial site, or perhaps a contemporary art installation (fig. 1.1a). Diving off Japan’s Okinawa Prefecture, we come upon a similar structure—an “alien crop circle” in the popular media (fig. 1.1b). We are astonished when we discover that the architects were a male great bowerbird (Ptilonorhynchus nuchalis) and a male pufferfish (Torquigener sp.), and that these structures only function in the context of courtship and mating. As amazed as we are by the structures’ builders, we should be awestruck by the aesthetics of the females they were built to impress. How intricate their aesthetics, how exacting their desires, must be in order to drive males to such cognitive and physical extremes? Why do females even bother to choose males on the basis of these structures, rather than simply mating at random?

Mating is an expensive, risky, and intimate interaction, and over an individual’s lifetime one expends time and energy on facilitating some matings, and time and energy on avoiding others. Who a chooser1 mates with and who she pairs with will affect how long she lives and how many healthy children and grandchildren she has. Mate choice determines which sperm fuse with which eggs, and therefore ultimately shapes how lineages split apart or merge together. It can drive the evolution of elaborate traits that hinder critical tasks like finding food and avoiding predators, in direct opposition to natural selection. The role of mate choice in both reproductive isolation among species and in sexual selection made it a key concept in Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859). There was widespread skepticism over his conjecture that mating preferences—a “taste for the beautiful,” in Darwin’s memorable phrasing—could explain the seeming paradox of so much exuberant scent, texture, and sound in nature. Accordingly, he devoted the bulk of his next major work, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871), to making the case for the central evolutionary role of sexual selection, particularly via mate choice.

Figure 1.1. (a) Bower of a satin bowerbird, Ptilonorhynchus violaceus, Queen Mary Falls, Queensland, Australia. Drawing from photo by Gail Patricelli. (b) Bower of a pufferfish, Torquigener sp., off Okinawa prefecture, Japan (Kawase et al. 2013). (c) Composite image of a displaying male great bowerbird (P. nuchalis) and bower as it appears to a choosing female, © 2017 John Endler.

Almost a century and a half later, mate choice continues to present a unique problem in evolutionary theory. Like predators coevolving with their prey, or hosts with their parasites, those courting and those choosing form a feedback loop, where chooser decisions can select for particular courter behavior and vice versa. In the case of mate choice, however, the same genome influences the behavior of both actors, and the interests of both are partly aligned and partly in conflict (Arnqvist & Rowe 2005). This kind of dynamic can lead to rapid evolution of elaboration of signals and choices within a species, which can lead to marked diversity of such signals and choices between species. Such divergent mate-choice patterns are often a prerequisite for reproductive barriers among species. Both the formation of new species, and the blending together of species via hybridization, depend on individual mate-choice decisions.

The study of mate choice is both fueled and complicated by its importance to our everyday experience. Mate choice forms our human identity: we are who we are because of a chain of highly improbable reproductive decisions, and our lives are in no small part defined by the people we desire, those with whom we have sexual relationships, and those with whom we reproduce. Our decisions to do so are regulated, to varying degrees in different times and places, by families, communities, and governments; few things are more painful than having our choices thwarted or overridden. It is hard to imagine music, prose, and poetry without love, jealousy, or heartache. And when we court each other and choose each other by starlight, we do so to the soundtrack of crickets and frogs doing the same. Mate choice surrounds us.

It is easy to make the case that mate choice is important, but how it actually evolves and how it actually works remains essentially mysterious. We are at a loss to explain much of the beauty in the world, from birdsong to the palette of colors on a coral reef, because we know that these things arise from mate choice, but we are still striving to understand how. We don’t understand why choosers pay attention to so many different things or how they integrate information into a unitary decision to mate. Perhaps most visibly, we still fail to agree on the importance of adaptive processes in mate choice. My first scholarly exposure to mate choice was in the fall of 1993, in a freshman seminar on “Sex and Evolution” led by Jae Choe. At the time, the field was consumed by a debate about the extent to which an individual’s mate-choice decisions impact the “genetic quality” of her offspring. Two decades later, we remain mired in, and limited by, the argument of whether or not mate choice is optimally designed to pick mates bearing “good genes.”

There are at least three reasons why the conversation hasn’t changed much over a generation. The first reason is that work on mate choice is hard to do; the core of mate-choice research involves inferring and predicting mating decisions indirectly and/or over long timescales. This is because mate choice as a phenotype is inherently slippery; we’re usually measuring behavioral decisions, which are inherently contingent on the stimuli presented, and can only be measured indirectly. We can readily measure the spectral reflectance of the components of a bower and calculate how they catch the sunlight over the course of a day, but it’s much more challenging to measure how these components influence the likelihood that a female will mate with the male who produced it. The next chapter deals with the technical challenges of measuring mate choice.

The second reason is the Balkanization of our approaches to studying mate choice. Those who study humans are generally associated with entirely different disciplines (anthropology and social and evolutionary psychology) than the majority of their colleagues working on non-humans (biology and its subfields, as well as comparative psychology). Biologists, moreover, are further subdivided into quantitative geneticists, behavioral ecologists, ethologists, and behavioral neuroscientists. The massive literature on mate choice is a mixed blessing, since it makes it difficult for any individual to have in-depth knowledge of more than one of these areas. A major goal of this book is to bring these fields together toward a synthetic understanding of mate choice.

The third and perhaps principal reason for the field’s slow progress is that we have always thought about mate choice primarily in terms of its functional consequences. Starting with Darwin (The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, 1871) and sexual psychologist Havelock Ellis (Sexual Selection in Man, 1905), and continuing on to the present (Andersson, Sexual Selection, 1994; Eberhard, Female Control: Sexual Selection by Female Choice, 1996; Arnqvist & Rowe, Sexual Conflict, 2005), the focus has not been on mate choice as an intricate psychological and behavioral process in its own right, but on mate choice as an agent of sexual selection. Evolutionary models sometimes rely on fanciful assumptions about mechanisms; conversely, empirical studies of mechanism frequently assume optimal design. Conversely, to the extent that those who study mate-choice mechanisms think about fitness consequences, they often assume these mechanisms are systems optimally designed to maximize the benefits of mate choice to choosers, rather than systems cobbled together from available genetic variation that sometimes lead choosers astray. It is tempting to think of choosers as actuaries, evaluating expected lifetime fitness, and taxonomists, recognizing conspecifics and heterospecifics, and executing each of these tasks both perfectly and separately. Yet relatively little attention is paid to how mate choice actually works, although this is crucial to understanding both how it evolves and how it imposes selection. How does a female bowerbird actually experience her choices (fig. 1.1c)? Our focus on courter traits, rather than chooser preferences, has produced some stumbling blocks for evolutionary theory: one important example is that the predictions of most sexual selection models depend entirely on whether the net direct benefits of mate choice are positive or negative, yet we seldom measure this directly. What is total selection on mate choice, and how does it affect the way preferences and sampling strategies evolve?

The standard approach in the mate-choice literature is to begin by reviewing theoretical and conceptual models, then discussing empirical evidence in light of the theory. Inspired by Darwin’s inductive approach in the Origin and the Descent, I have attempted to turn this approach upside down and interpret theory in light of what we know about how mate choice works. Accordingly, I focus this first section of the book on natural history—a broad description of the mechanisms, ontogeny, and phenotypic expression of mating preferences and mate choice. I have deliberately chosen my language to minimize a priori assumptions about any adaptive functions of choosing particular mates over others. In the second section, I use this perspective to address how mate choice evolves and acts as an agent of selection, and how it generates fitness consequences for individuals and evolutionary consequences for populations and species.

Part of the challenge of studying mate choice arises from the enormous scope of mate choice as a phenomenon. The contemporary literature on mate choice is immense. Choice can range from the simplicity of a single-celled protozoan exchanging genes only with another individual emitting a particular signaling molecule, through the protracted mutual courtship of humans and other vertebrates. What these vastly ...