![]()

Chapter 1

Domestic Politics

TO UNDERSTAND THE FACTORS that gave rise to the Smoot-Hawley tariff, we need to understand the process by which Congress handled tariff revisions and the political forces at work in the late 1920s.

The U.S. Constitution gives Congress the authority to levy duties on imports. From the very beginning, the use of this power was controversial. Throughout the nineteenth century, the debate centered on whether tariffs should be levied to raise revenue for the federal government, or to protect domestic industries from foreign competition as well. With the introduction of the income tax in 1913, tariffs were no longer a major source of government revenue.1 As a result, Congress began to use tariffs mainly to protect domestic industries from imports. The only question was whether a domestic industry’s desire to stop foreign competition should take precedence over the interests of consumers and exporters in having an open market for imported goods.

In confronting this question, Congress ran up against deeply rooted regional differences on matters of trade policy. For most of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, proponents of high protective tariffs came from the North, where manufacturing industries faced competition from imports. Opponents of high tariffs came from the South, where cotton and tobacco farmers exported their crops to foreign markets. Interests in the Midwest were mixed. Midwestern farmers were consumers of manufactured goods and wanted lower tariffs on industrial goods to promote competition and reduce prices. At the same time, they also wanted high tariffs on agricultural imports that competed with the goods they produced.

The positions of the two main political parties reflected these regional differences. Prior to 1930, Republicans were mainly elected from the North and Midwest and advocated a policy of protectionism, although they sometimes had to accommodate the Midwest’s mixed position. Democrats were mainly elected from the South and opposed high tariffs out of concern that trade restrictions would ultimately reduce southern exports. Hence, whenever the Republicans were in power, they voted to impose or maintain high tariffs; whenever the Democrats were in power, they voted to lower tariffs.

Of course, for any particular member of Congress, the economic interests of one’s constituents trumped partisan loyalties. A Democrat elected from Pennsylvania or Louisiana would not support the party’s low tariff position if it meant allowing more imports of steel or sugar. Similarly, a Republican elected from Wisconsin or Iowa would not support the party’s high tariff position if it meant increasing the cost of manufactured products consumed by farmers. As John Sherman (1895, 2: 1128), a Republican senator from Ohio for thirty-seven years after the Civil War, wrote: “It is easy to formulate general principles, but when we come to apply them to the great number of articles named on the tariff list, we find that the interests of their constituents control the action of Senators and Members.”

As an institution, Congress was biased in favor of high tariffs because of an asymmetry in the political influence between those that favor reducing imports and those that favor unrestricted imports. As a general matter, domestic producers facing foreign competition are very politically active in advocating restrictions on imports, whereas consumers and exporters who are harmed directly or indirectly by import barriers tend to be politically inactive. This asymmetry in political activism reflects a simple cost-benefit calculation: the benefits of a tariff are highly concentrated on a few producers who are strongly motivated to organize and defend that policy, whereas the costs of tariffs are spread widely among many consumers for whom it does not pay to organize any serious opposition.

This bias was highlighted by political scientist E. E. Schattschneider in his classic study of the Smoot-Hawley tariff, Politics, Pressures, and the Tariff, published in 1935. He focused on the public hearings that Congress held before drafting the tariff legislation. Expecting that the economic interests supporting and opposing the tariff legislation would be approximately equal, Schattschneider (1935, 285) found instead that the pressures exerted upon Congress were “extremely unbalanced. . . . the pressures supporting the tariff are made overwhelming by the fact that the opposition is negligible.” Schattschneider (1935, 109) described the highly skewed forces confronting Congress this way: “The primary, positive, offensive activity of domestic producers seeking increased duties almost completely dominated the whole process of legislation. The pressures from this quarter were more aggressive, more powerful, and more fruitful by a wide margin of difference than all of the others combined.” In fact, opposition to higher tariffs by consumer groups, exporters, or importers was “usually inconsequential.”2

What explained the imbalance in political power between those in favor of higher tariffs and those opposed? In Schattschneider’s view:

The political agitation concerning the tariff is profoundly influenced by the fact that, in many instances, the benefits of the legislation to an individual producer are obvious while many of the costs are obscure. The benefits, moreover, are directly associated with a single duty, or at most, a few duties, while costs tend to rise from multitudes of them. Benefits are concentrated while costs are distributed. (127–28)

The nature of international trade and the geography of domestic production reinforced Congress’s bias in favor of high tariffs. The United States imported a highly diversified set of goods, making it likely that some producers in every state would be competing against imports. For example, wool producers in Ohio and Colorado, steel producers in Pennsylvania and Ohio, glass producers in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, textile producers in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, and many others, all had an interest in reducing foreign competition. This meant that the geographic political base that supported protectionist trade policies, while concentrated in the north, was generally very broad. Meanwhile, U.S. exports were composed of a limited number of goods that were produced in a few specialized regions of the country, such as cotton and tobacco in the Deep South. This meant that the geographic base for supporting open trade policies was relatively narrow.

In addition, members of Congress engaged in logrolling—vote trading—as a way of maintaining high tariffs. For example, a representative from Ohio, whose constituents wanted to stop imports of cheap wool, might agree to vote for a higher tariff on steel to benefit Pennsylvania, or cotton textiles to benefit Massachusetts, if the representatives from those states would vote in favor of a higher tariff on wool. The benefits to the Ohio wool producers from the wool tariff were much more apparent than the higher costs of steel and textile goods to consumers in Ohio. Because this kind of vote trading was a common practice in the halls of Congress, members whose constituents would benefit from lower tariffs found it hard to gain support.

After the Civil War, Congress revised the tariff code about every decade or so. These revisions depended on shifts in political power and the state of the economy. If an election transferred power from one party to another, the newly elected party usually enacted a new schedule of import duties that better served the interests of its constituency. If the economy was doing well, Congress would face little political pressure to change the existing duties, but if the economy was in a recession, the demands for new import restrictions would invariably increase.

These last two factors make it somewhat surprising that Republicans proposed a tariff revision in 1928. Less than six years had passed since they had last altered the tariff code with the Fordney-McCumber tariff in September 1922. Since that time, the Republicans had maintained political control and the economy had been performing well. In fact, the U.S. economy was booming in 1929: during that year, real GDP increased more than 6 percent and the unemployment rate was about 3 percent (Carter and Sutch 2006, series Ca9 and Ba 475). Manufacturers were not complaining about surging imports or intensified competition from foreign producers. The nation produced $47 billion in manufactured goods, but imported just $854 million in dutiable manufactured goods. This meant that the import penetration ratio (imports as a percent of domestic consumption) was less than 3 percent. Furthermore, American manufacturers as a whole were much more dependent on exporting to foreign markets than they were threatened by imports: in 1929, about 8 percent of U.S. manufacturing output was exported and the United States enjoyed a $1.4 billion trade surplus in manufactured goods.

In fact, most imports did not affect domestic manufacturers at all. Two-thirds of U.S. imports entered duty-free. They were either consumer goods (such as coffee, tea, and bananas) or raw materials used by industry (such as silk, petroleum, rubber, copper, tin, fertilizer, and cocoa beans) that were either not produced at home or produced in insufficient quantity to meet American demand. The remaining one-third of imports competed with domestically produced products, and consequently they were slapped with high tariffs. Examples include duties of 94 percent on imported sugar, 62 percent on silk goods, 51 percent on wool and wool manufactures, 50 percent on cotton manufactures, 60 percent on glass and pottery, and so on. These tariffs significantly reduced imports and allowed domestic producers in these categories to dominate the U.S. market. Small, high-cost producers always hoped for even higher tariffs to eliminate the residual imports entering the U.S. market and expand their sales. But by and large, the American economy was doing well in the late 1920s, and this prosperity meant that there was no significant political pressure from industry to further limit imports.

Why, then, did the Republicans propose a tariff revision in 1928? The main reason was that another segment of the nation’s economy was not doing well: agriculture. The 1920s was an exceptionally difficult decade for American farmers. Foreign demand for U.S. agricultural goods soared during the boom years of World War I, and farm prices doubled between 1915 and 1918. This sparked a wave of land speculation and large investments in machinery and buildings as farmers sought to expand their production capacity. It also pushed farm indebtedness to record levels. When a sharp tightening of monetary and credit conditions led to an unexpected collapse of commodity prices in late 1920 and early 1921, heavily indebted farmers faced a huge financial squeeze. Although manufacturing industries were also slammed by the 1920–21 recession, they quickly bounced back and grew rapidly for the rest of the decade. Agriculture remained in a prolonged and painful slump, with farm income failing to regain its prewar level until 1925 and remaining flat for the rest of the decade.

As the real burden of mortgage debt rose with the fall in commodity prices, farms began to fail in increasing numbers. Foreclosures rose from 3 percent of farms between 1913 and 1920 to 11 percent between 1921 and 1925, and reached an astounding 18 percent of all farms between 1926 and 1929 (Alston 1983). During these years, the entire rural economy suffered from falling farmland prices, mortgage foreclosures, and rural bank failures. The contrast between prosperous industries in the East and struggling farms in the Midwest fueled agrarian resentment against industrial and commercial interests. Manufacturers were protected against foreign competition by high tariffs. Farmers felt that they paid for the tariff through higher prices and now they wanted equal consideration from the politicians in Washington.

With nearly a quarter of the American labor force employed in agriculture, Congress could not ignore the farm sector’s plight. Congress began considering new policies to ensure “equality for agriculture” and give equal assistance to farm producers. Because the average tariff on imported agricultural commodities was about half of the average tariff on imported manufactured goods, some thought parity for agriculture could be achieved through a higher tariff on the products that farmers sold or a lower tariff on the goods they purchased. As a result, many agricultural interest groups, represented by such organizations as the National Grange, the American Farm Bureau Federation, and the National Farmers Union, supported the idea of tariff equality.

However, they sought to achieve this mainly through an increase in agricultural tariffs, rather than a decrease in industrial tariffs. “There was practically no direct attack upon the principle of a high tariff by the national farm organizations,” notes Conner (1958, 37). “Instead, the basic approach of these groups was an attempt to secure parity in tariff rates with industry. . . . the thinking of organizational leaders was developed within the framework of a high tariff structure, the emphasis being upon raising agricultural rates to obtain parity with industry, rather than upon lowering any or all rates.” In fact, farm groups planned to speak out against industrial tariffs only if the tariff on agricultural goods could not be increased to match those on industrial products. The National Grange’s threatening slogan was “a tariff for all or a tariff for none.”

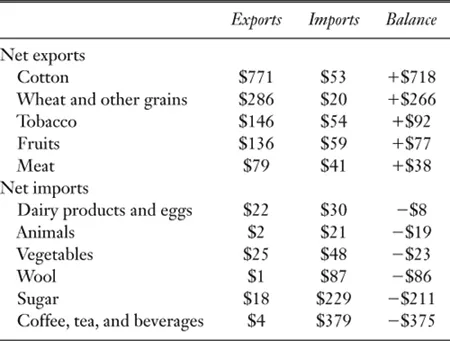

The big problem with using tariffs to assist agriculture was that it would not help the large number of farmers who produced goods for export. Table 1.1 presents the U.S. exports and imports of agricultural goods by commodity type. The United States was a large net exporter of key crops such as cotton and tobacco, produced in the South, and grains such as wheat, produced in the Midwest: the nation sold one-half of its cotton, one-third of its tobacco, and one-fifth of its wheat and flour to foreign markets. The price at which these commodities were sold was determined by the world market. Imposing higher duties on the trivial amount of imports of these goods could not provide farmers with any relief because it would have no effect on the prices that farmers received for their crops.

TABLE 1.1.

U.S. Foreign Trade in Agricultural Products, 1929 (in US$ millions)

Source: Statistical Abstract of the United States (1931), 675, 574–84.

Furthermore, the small amount of these imports did not really compete with domestic producers: long-staple cotton from Egypt was quite different from the cotton produced in the Uni...