![]()

I

FROM CUNEIFORM TO CLASSICAL CIVILIZATION

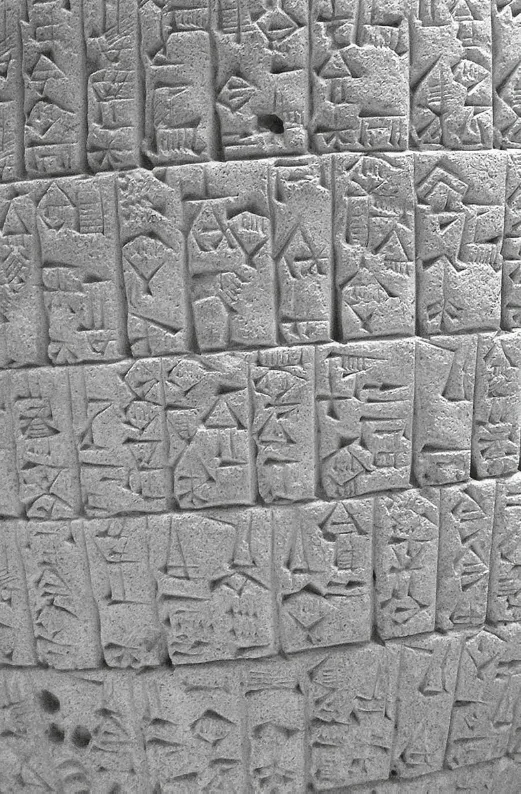

Detail of the Enmetena cone, ca. 2400 BCE. The cone is a Sumerian document commemorating the conquest of the city of Umma by Enmetena, the king of the rival city of Lagash. The ruler’s claim for war reparations is the earliest known record of compound interest.

Finance began with the first cities—and vice versa. This first section focuses on the parallel emergence of urban civilization and finance. The joint emergence of finance and civilization in the ancient Near East teaches an important lesson. Higher levels of political and social development demand complex economic organization and technology. Financial infrastructure made many of the advances of urban society possible—and it still does. Humanity gave up a certain measure of economic innocence on the developmental path to urbanism, but at the same time it began a process of discovery and invention that fundamentally changed human experience.

The first four chapters trace the extraordinary arc of financial development in the ancient Near East. I argue that the invention of a way to express the exchange of value through time created a novel model of thought: a capacity to forecast economic outcomes and to treat past, present, and future values as equally concrete. With the invention of finance, people lived their economic lives in an exquisitely articulated framework of time. Stepping into this quantified temporal framework opened up many new possibilities. Some were ways of mitigating risk. For example, financial thinking was embedded in the earliest agricultural civilizations because of the need to plan farming and husbandry operations, and to record promises of future commodity deliveries. However, financial tools were also part of waging war. The earliest record of a boundary dispute in antiquity includes a demand for reparations with punitive compound interest.

Neither finance nor urban society remained stationary through the first two millennia of their coexistence, and the chapters on the ancient Near East emphasize the way in which financial tools were adapted to trade as well as to agricultural production. Finance became a mechanism for facilitating complex mercantile operations stretching from Anatolia to the Indus.

The chapters on Athens and Rome show how two different cultures adopted and transformed the Near Eastern financial legacy. I argue that financialization in fact made both the Athenian and Roman economies possible. Both were reliant on imported grain. Their financial systems developed, in part, to allocate investment capital to support the commodity trade and to allocate the risk of this trade.

Two aspects of Greek civilization are highlighted: law and money. The simple existence of courts in Athens created enforceable property rights and attracted investors. I claim that the courts also had an important intellectual and perhaps cognitive effect. Trade disputes were regularly argued before juries of hundreds of citizens, and this must have created an intensely financially literate society. The monetization of the Athenian economy was an equally important step. Recently, scholars have argued that it played a central role in the transition to the political phenomenon for which Athens is most famous: democracy. Money became both a tool for sharing the Athenian economic success and an instrument for aligning personal loyalties to the state.

This section finishes with a chapter on Rome and a picture of a fully financialized ancient economy—like Athens, an import society that sustained one of the largest cities in the world via commodity trade. Personal wealth in Rome played a key role in political power, and fortunes were sustained through a variety of direct and indirect investment opportunities. Debt played an important role in the Roman financial system, and it left its trace in a series of financial crises.

One of the Rome’s most innovative contributions to finance was the creation of shareholder companies that supplied services to the growing needs of the state. Investors in these companies, called publican societies, participated in profits from tax-farming, public works construction, and provisioning Rome’s armies. Publican societies were the world’s first large-scale publicly held companies—something like modern corporations. Their shares fluctuated in value and were held broadly by citizens of Rome. I argue that these financial instruments played a crucial role in the political structure of Rome at a certain juncture in its history, because they provided a means to reallocate the economic benefits of Rome’s expansion and conquest among key political constituents.

![]()

1

FINANCE AND WRITING

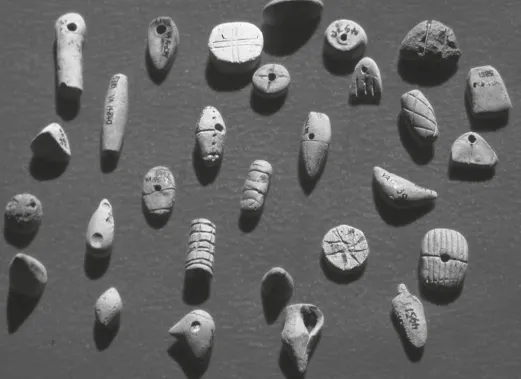

Clay tokens from the ancient Near East symbolizing economic commodities. They are thought to have been used as a system of accounting and are also believed to be the precursors of the world’s first written language.

This chapter explores the appearance of finance as a technology in the ancient Near East and the role it played in the unique features of the world’s first large-scale urban societies. Mesopotamia gave the world its first cities, first written language, first laws, first contracts, and first advanced mathematics. Many of these developments directly or indirectly came from financial technology. Cuneiform writing, for example, is an unintended by-product of ancient accounting systems and contracts. Babylonian mathematics owes its development to arithmetic and calculation demanded by its financial economy. The first mathematical models of business growth and profit appeared 4,000 years ago. The legal system of the Babylonians depended crucially on the use of notarized and witnessed documents and contracts establishing individual rights and obligations, many of which are similar to modern financial instruments and contracts. The first mortgages, deeds, loans, futures contracts, partnership agreements, and letters of credit appear as cuneiform documents dating to the second millennium BCE or earlier. In short, the dramatic development of urban society beginning more than 5,000 years ago involved the simultaneous development of new kinds of institutions and processes, many of which were economic and financial in nature. These financial practices, embedded in larger social and economic institutions, are what I refer to as the hardware of finance in the Introduction.

This chapter also explores how financial tools changed the way people thought. Financial technology made possible not just financial contracts but also financial thinking—conceptual ways of framing economic interactions that use the financial perspective of time. Borrowing, lending, and financial planning shaped a particular conceptualization of time, quantifying it in new ways and simplifying it for purposes of calculation. This way of thinking and specialized knowledge, in turn, affected and extended the capabilities of government and enterprise. This conceptual framework is what I refer to as the software of finance in the Introduction.

Finance relies on the ability to quantify and calculate and reason mathematically. Thus, much of this chapter focuses on the development of mathematical tools in ancient times. Another basic ingredient of finance is the dimension of time. Finance requires the measurement and expression of time and this chapter explores time technology in some depth. Finally, it deals with record-keeping, contracting, and the legal framework of finance. This is because finance is mostly about future promises. Promises are meaningless without the capacity to record and enforce them.

The first evidence of financial tools appears in the context of the early urban, agricultural societies of the ancient Near East, roughly contemporaneous with the beginning of the Bronze Age. The prehistoric roots of urban society in the ancient Near East extend back perhaps 7,000 years. By 3600 BCE, the cities of ancient Sumer arose around the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what is now modern Iraq—a location well suited to cultivation of grain and livestock but lacking in other needs, such as timber, copper, and tin. These last two items were especially important, because they are the essential ingredients for making bronze—a metal vital for ancient warfare. Archaeological evidence suggests that Sumerian cities relied on long-distance trade for these key commodities. They also traded for exotic prestige items, such as ivory and precious stones, which played a role in the intensification of social and political hierarchy—likewise a hallmark of civilization.

In short, the economy of ancient Near Eastern civilization required methods for producing and distributing basic foodstuffs locally to a concentrated urban populace and also ways of obtaining goods from afar. The basic unit of finance—a contract that extends through time—addressed both of these economic imperatives. As ancient unban societies of the Near East grew in scale and scope (i.e., density of population and geographical range of trade), they relied increasingly on intertemporal contracting techniques (i.e., finance). Finance first appeared with one of humanity’s most remarkable inventions—writing; the ability to memorialize something now that can be interpreted unambiguously in the future. Even writing, however, had its precedents, and these emerged out of a financial imperative.

We begin this chapter with the discovery of an essential piece of financial hardware: counting, accounting, and contracting tools.

TEMPLES AND TOKENS

He built the town wall of Uruk, (city) of sheepfolds,

of the sacred precinct of Eanna, the holy storehouse.

Look at its wall with its frieze like bronze!

Gaze at its bastions, which none can equal!

Take the stone stairs that are from times of old,

Approach Eanna, the seat of Ishtar,

the like of which no later king—no man—will ever make.1

One of the earliest literary works ever written tells the story of Gilgamesh, the hero who traveled to distant lands to obtain timber for building a temple in his city. The passage above is from the epic of Gilgamesh.2 It sings the praises of the majestic city walls and the Eanna temple of Uruk, the birthplace of Mesopotamian civilization. Although the text is eloquent, the cuneiform script in which the epic was first recorded owes more to merchants and accountants than it does to poets. Cuneiform was not invented for writing poetry but for accounting and business, and Uruk may have been the original site of both. Of course, it is difficult to precisely pinpoint the time and location of the development of any technology, but some of the earliest material remains of writing—and the precursors to writing—have come to light at Uruk. Scholars working on the beginnings of writing believe that it evolved from a peculiar system of symbolic accounting records associated with the Uruk temple economy.

In 1929, the German archaeologist Julius Jordan excavated the heart of the ancient city—Uruk’s central temple complex. This Indiana Jones–scale dig revealed Jordan’s long-sought prize, the “sacred precinct of Eanna, the holy storehouse,” the place where the fertility goddess Inanna was worshipped but also where goods and commodities were distributed to the populace. Near the temple, Jordan and his crew of excavators found the stone steps of the temple—exactly as described in the epic of Gilgamesh. Jordan kept a careful record of all his discoveries—not only the monumental architecture, but even small artifacts and objects that were unearthed in the dig. In his journals, he documented curious little tokens “shaped like commodities of daily life: jars, loaves and animals” that came to light around the temple complex. These little objects went largely unstudied until Professor Denise Schmandt-Besserat, a scholar at the University of Texas at Austin, began to analyze them in systematic fashion.

Born and educated in France, Schmandt-Besserat began her research at Radcliffe in a fellowship program for promising female scholars. She became fascinated with the question of whether clay was used as a technology before the invention of pottery. This puzzle first took her to museum collections to search for early clay objects. She became a research fellow in Near Eastern Archaeology at Harvard’s Peabody Museum, and there rediscovered the mystery of Jordan’s little tokens. Denise moved to the University of Texas in the 1970s, where she continued her work on the tokens—painstakingly tracking down every recorded mention of them in archaeological digs in the Near East and visiting all the museum collections that contained them.

I first met Denise when I was a graduate student in art history at the University of Texas at Austin, and she was a curator at the University of Texas Art Museum. She was my teacher, and I was able to observe directly her path-breaking work. I had no idea at the time that it would be the finance implicit in the token system—rather than the art of it—that would ultimately capture my interest.

While other scholars of the ancient Near East were studying big problems like the evolution of temple architecture, the political history of ancient city-states, and the question of how the ancient climate affected farming and urbanism, Denise concentrated her efforts on laboratory analysis and documentation of the tokens. She established that tokens predated even the ancient city of Uruk. They appeared in prehistoric sites throughout the Near East as early as 7000 BCE. Whatever these things were—counters, game tokens, or mystical symbols, they were used by many different peoples and cultures long before the invention of writing.

The objects are about the size of game pieces. Their stylization and simplification suggest that they were standardized for easy recognition—abstract and simple rather than realistic. A systematic organization of the tokens by form and place of discovery led Denise to a stunningly novel hypothesis. Her analysis linked them iconographically to the earliest pictographic writing on clay tablets found in the oldest parts of Uruk.

The oldest Uruk tablets were made circa 3100 BCE by scribes who took wet lumps of clay, shaped them into lozenges, and wrote on them with a wooden stylus. The stylus had a sharp end and round end—one end for lines and the other for dots. Laid sideways, the stylus could also make triangular and cylindrical impressions. The combination of these formed a lexicon that scholars have now concluded was the first writing.

What Schmandt-Besserat famously recognized is that the pictographs on these early tablets were essentially pictures of the little clay tokens. For instance, she showed that the pictograph for cloth could be traced to a round, striated token. The symbol for sweet evolved from a token shaped like a honey jar. The symbol for food evolved from a token shaped like a full dish. Most represented commodities from daily life: lambs, sheep, cows, dogs, loaves of bread, jars of oil, honey, beer, milk, clothing, ropes, wool, and rugs, and even such abstract goods as units of work. Apparently, these were the items once contained in the goddess Inanna’s “holy storehouse.” These beautiful little objects were not about art—they were about economics—commodities in the Sumerian redistribution system.

The connection between the tablets and the tokens helps explain the function of each. Virtually all of the earliest tablets from Uruk were accounting documents recording the transfer of goods and commodities. They were administrative records used by some central governing economic authority—almost certainly the temple.

The tokens evidently were used in the same kind of process, perhaps by the world’s first accountants sitting in front of the storehouse door of the temple, keeping track of how much went in and out. In a preliterate society that needed a way to keep track of economic transactions, the tokens were natural symbols that co...