![]()

1

Introduction

After pondering the disparity in income between rich nations and poor, Robert Lucas famously stated: “Once one starts to think about [the problem], it is difficult to think about anything else.”1 Humanitarians, policymakers, and scholars have joined Lucas in addressing the determinants of development; and in this volume, I, a political scientist, join them.

Among those who seek to account for the disparities in income that mark the modern world, economists, such as Lucas, stand supreme. Not only do they rank among the most skilled and insightful of those who study development, but also they dominate the agencies that fund programs and design policies for those who strive to achieve it. But clearly, the problems bedeviling efforts to promote prosperity in the developing world are not purely economic in nature. Some arise from cultural values and religious beliefs; others from biological and environmental forces; and still others from politics. I shall focus on the impact of politics. I shall focus in particular on politicians, their use of power, and their impact on development.

Development, I contend, contains two elements: one economic, the level of prosperity; and the second political, the degree of security. From this perspective, societies can be considered more developed the greater their prosperity and the more secure the lives and property of those who inhabit them. Some might object to the use of income, and especially average income, as a measure of development. But clearly the attainment of other valued outcomes is costly and prosperous societies are better positioned to secure them than are those that are poor. As for security, I take counsel from Hobbes, who noted that where “the life of man is nasty, poor, brutish and short,” there is “no place for industries, because the future thereof is uncertain … no knowledge of the face of the earth; … no arts; no letters; and what is worst of all, continuous fear, and danger of violent death.”2 Both prosperity and security are valuable, then, not only in their own right but also because they make possible the attainment of other values.

Throughout this book, I probe the political foundations of development.

Method and Substance

Most who study development proceed “cross-sectionally”; that is, they compare poor nations to rich ones and note how differences in, say, education, gender equality, investment, or corruption relate to differences in standards of living. But development is a dynamic phenomenon and involves change over time. It is best studied, then, by seeing how nations evolve. Not only that: only a handful of nations in today’s developing world have achieved a standard of living comparable to that of nations in the developed world; and in many, life and property remain imperiled. The number of “successes” is small; and because most of these reside in the Pacific Rim, so too is the amount of variation in the sample they provide. Today’s world thus provides us little information. The implications are profound: today’s world supplies little insight into how nations develop.

In response to this difficulty, I turn to history. Rather than proceeding cross-sectionally, and comparing poor countries with rich in the contemporary world, I proceed “longitudinally” and explore, for a given set of countries, how they changed over time. For reasons that I will soon discuss, I focus on England and France in the medieval and early modern periods. At the end of the latter, England stood poised to undergo the “great transformation” whereas France stood on the verge of political collapse. Attempts to isolate the factors that rendered the one more successful than the other can therefore offer insight into the factors that promote or impede the attainment of prosperity and security.

To use historical materials in this fashion, we have to assure ourselves that at least two conditions are met. The first is that the historical cases be sufficiently similar that inferences can be drawn from their divergent responses to similar stimuli. The second is to find a way of moving from “what is known”—the historical cases—to what cannot yet be known—the determinants of development in the contemporary world. We now turn to these issues.

TURNING TO HISTORY

The principal justification for drawing inferences from a comparison between England and France is that politically, economically, linguistically, and culturally, in the medieval and early modern periods, England and France shared important characteristics in common.

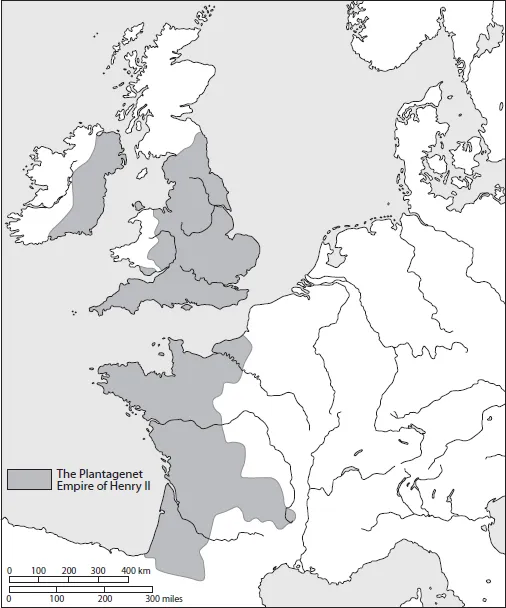

The England we first encounter was ruled by the Normans. And the Normans, like the Angevins that followed, presided not only over England but also over their “homelands” in what now is France (see figure 1.1). England’s governing classes held properties on both sides of the channel, which they crossed and recrossed to manage and defend. The ruling lineages intermarried and incessantly fought each other. On both sides of the channel, the elite spoke the same language and until the sixteenth century belonged to the same church. That the two cases shared such basic characteristics in common, I argue, enables us to relate their differences to variations in the developmental outcomes that emerge over time: the one, becoming richer and more powerful; the other, a failed state.

FIGURE 1.1. England, France, and the Angevin dynasty. Source: “Henry II, Plantagenet Empire” by Cartedaos (talk) 01:46, 14 September 2008 (UTC), own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

USES OF THE PAST

Turning to a second challenge, we ask: How are we to employ our knowledge of history to gain insight into the contemporary world?

We do so by noting that in the medieval and early modern periods, Western societies were agrarian and that the underdeveloped nations remain largely so today. The attributes that commonly mark agrarian societies offer a framework that enables us to compare the two sets of cases; they enable us to treat them as members of a similar class. While accommodating, the framework (see box 1.1) is also powerful: it highlights regularities that enable us to draw on what is known about one set of cases to shed light on another. By so doing, it enables us to better comprehend the impact of power upon the process of development.

AGRARIAN ECONOMIES

As can be seen in box 1.1, two powerful regularities characterize agrarian economies, one governing production and the other consumption. The first is the law of diminishing returns. Derived by David Ricardo, a student of England’s agrarian economy, the law states that as population grows, because the quantity of land remains fixed, per capita output declines. The first settlers would work the most productive land; as the population grows and people spread out, they then move to lands of lower quality. Should they instead remain on the most fertile plot, as their numbers increase, they would have to farm more intensively or make use of less productive labor, such as the aged. The increase in population therefore results in less output per unit of labor. By the law of diminishing returns, as this regularity is known, in agrarian societies, over time, average incomes decline and people become poor.3

BOX 1.1. An Agrarian Society

The Economy. Rural economies abide by the law of diminishing returns. As populations grow, in the absence of technical change, incomes decline. And by Engel’s law, poor people devote a greater percentage of their incomes to the consumption of food than do those who are better-off. Taken together, diminishing returns and Engel’s law imply that if an economy is agrarian, its people will be poor.

The Society is organized by kinship.

Families constitute the active agents of an agrarian society.

In the economy: They control not only the spending but also the generation of income.

In the polity: They govern the use of power.

In addition, the nature of the assets they control shapes the preferences they hold.

From these characteristics, several phenomena emerge:

Migration: To elude the impact of diminishing returns and thereby prosper, people migrate; they seek additional land. Note the implication: Contrary to common beliefs, agrarian societies are not static. People move frequently, either as families or hordes.

Specialization and Trade: To elude the impact of diminishing returns, people specialize in production and exchange. They make intensive use of the productive factors with which they have been comparatively well endowed, be it meadows, wetlands, forests, or a position beside a waterway. Harvesting more than they wish to consume, they exchange the surplus for goods produced by others. Note the implications: (1) Not only farming but also trade takes place in agrarian societies. Not only farmers but also merchants inhabit them. In addition to farms, there are towns. (2) Relations between town and country mark the politics of agrarian societies. The two quarrel over the price of food: something that town dwellers buy and consume and that rural dwellers produce and sell.

The second law characterizes consumption. Named after Ernst Engel—a statistician who studied household economics in Germany—the law holds that the lower a person’s income, the greater the percentage of her budget that she will spend on food. Food is a necessity, after all; to survive, a person must eat. Should she become poor, she will therefore curtail her expenditures on other commodities and devote her income to the purchase of food.4

The two laws pertain to individuals who produce and consume. While thus “micro” in scope, they generate “macrolevel” implications. By Engel’s Law, poor societies are agrarian; and by the law of diminishing returns, agrarian societies become poor.5 These regularities permeate both premodern Europe and the less developed portions of the contemporary world and mark them both as underdeveloped.

There are few laws in the social sciences. That two of the few we possess pertain to agrarian societies is fortuitous and encourages us to believe that premodern Europe and the contemporary developing world may abide by common logics. They encourage us to believe as well that insights extracted from the one can deepen our understanding of the other, even if the two inhabit different places and times.

From these laws, other regularities follow, and these too offer points of entry for those who wish to use history for the study of development. To fend off declines in income in agrarian societies, people specialize in production and engage in trade. One result is regional differentiation, with wine, say, being produced in one location; timber and charcoal in another; and meat, hides, and dairy products in yet a third. Another is commerce. As trade and markets span these diverse settings, they enable people to exchange the surpluses they produce locally for goods that may be produced more cheaply in other locations. In response to diminishing returns, people also migrate. They venture forth in search of new places to settle. As we shall see, regional differentiation and migration—both responses to decreasing returns—shaped the politics of development in medieval and early modern Europe and shapes it in the developing world today as well.

As suggested by Engel’s Law, a third, “macrolevel” implication emerges: as incomes rise, the relative size of the rural sector declines. With development, agriculture gives way to industry and manufacturing, with factories replacing farms, towns displacing villages, and labor shifting from farming to commerce and industry. Development thus involves “structural change,” in the words of some,6 or a “great transformation,” in the phrasing of others.7 To study the political foundations of development is to study the politics of these changes.

Two economic “laws” thus provide a structure that enables us to place medieval and early modern Europe within the same framework as the contemporary developing world and to focus on a common set of themes: regional specialization, migration, and the impact of structural change.

A last major regularity characterizes agrarian societies. It is the importance of kinship. In both agrarian and industrial societies, families govern consumption; they allocate the household budget. But in agrarian societies, they govern production as well; they assign tasks in home and field to the members of the household. Kinship and the family also govern the polity. Offices and titles are transmitted by the rules of descent. Polities are often governed by dynasties and localities by groups of kin. And it is the family that provides security: by brandishing arms, its members deter those who might seek to encroach upon them.8 When we study the economics and the politics of agrarian societies, be they in the historical West or the contemporary developing world, we shall focus on the role of the family.

Because of their agrarian nature, medieval and early modern Europe and the developing world share key features in common. This common set of features constitutes what I call a “political terrain”: a setting within which politicians compete for power. As we shall see, the composition of that terrain determines what kinds of actions are “winning” and therefore how those with power are likely to behave. Examining the historical cases enables us to infer the features that appear to have led to the productive use of power in one case and to its destructive use in another, thus suggesting lessons that should inform our understanding of development in the contemporary world.

THE ROLE OF EMPIRE

Many will bridle at this approach. Conceding the presence of commonalities, they would also stress the importance of differences between medieval and early modern Europe and the developing world today. The challenge of development today differs from that in the past, they would contend, for nations today are attempting to develop in a world dominated by those who are far richer and more powerful than themselves.

By way of rejoinder, I advance two counterarguments. First, as does the developing world today, in the medieval and early modern periods, Europe confronted others whose wealth and pow...