![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

I have never concealed from you my belief that a little shooting would be an essential preliminary to effective change in Indonesia; but it makes me sad to think that they have begun with the wrong people.

—SIR ANDREW GILCHRIST, BRITISH AMBASSADOR TO INDONESIA, OCTOBER 5, 1965

IN A LITTLE OVER SIX MONTHS, from late 1965 to mid-1966, an estimated half a million members of the Indonesian Communist Party (Partai Komunis Indonesia, or PKI) and its affiliated organizations were killed.1 Another million or so were detained without charge, some for more than thirty years, and many of them were subjected to torture and other inhumane treatment. Few, if any, of the victims were armed, and almost all those killed and detained belonged to what were at the time lawful political and social organizations. This was not a civil war. It was one of the largest and swiftest, yet least examined instances of mass killing and incarceration in the twentieth century.

The consequences of the violence were far-reaching. In less than a year, the largest nongoverning Communist party in the world was crushed, and the country’s popular left-nationalist president, Sukarno, was swept aside. In their place, a virulently anticommunist army leadership seized power, signaling the start of more than three decades of military-backed authoritarian rule. The state that emerged from the carnage, known as the New Order, became notorious for its systematic violation of human rights, especially in areas outside the heartland, including East Timor (Timor Leste), Aceh, and West Papua, where hundreds of thousands of people died or were killed by government forces over the next few decades. The violence also altered the country’s political and social landscape in fundamental ways, leaving a legacy of hypermilitarism along with an extreme intolerance of dissent that stymied critical thought and opposition, especially on the Left. Perhaps most important, the events of 1965–66 destroyed the lives of many millions of people who were officially stigmatized because of their familial or other associations with those arbitrarily killed or detained. Even now, more than fifty years later—and some twenty years after the country began its transition to democracy—Indonesian society bears deep scars from those events.

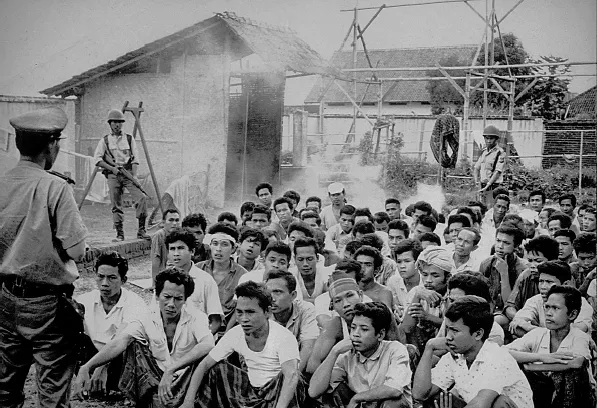

FIGURE 1.1. Suspected PKI member arrested by soldiers in Jakarta, November 1965. (Rory Dell/Camera Press/Redux Pictures)

In its sweep and speed, and its profound political and social implications, the violence of 1965–66 was comparable to some of the most notorious campaigns of mass killing and imprisonment of the postwar period, including those that occurred in Bosnia, Cambodia, and Rwanda, and it far surpassed other campaigns that have become iconic symbols of authoritarian violence in Latin America, such as those in Argentina and Chile. “In terms of the numbers killed,” the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) wrote in 1968, “the anti-PKI massacres in Indonesia rank as one of the worst mass murders of the 20th century, along with the Soviet purges of the 1930s, the Nazi mass murders of the Second World War, and the Maoist bloodbath of the early 1950s.”2 And while there is still no consensus on the matter, some scholars have described the Indonesian violence as genocide.3 Yet half a century later, this violence remains virtually unknown internationally. Thus, the World History Project website entry for the year 1965 includes the fact that “Kellogg’s Apple Jacks Cereal First Appears,” but fails to mention the killing of half a million people in Indonesia.4

Even inside the country, the events of 1965–66 are still poorly understood, having only recently become the focus of serious discussion by historians, human rights activists, and the media. The massive production of testimony, memoir, truth telling, and forensic investigation—to say nothing of reconciliation, memorialization, and justice—that has followed virtually every genocide in the twentieth century has scarcely begun in Indonesia. Moreover, in contrast to most of the great mass killings of the past century, these crimes have never been punished or even properly investigated, and there have been no serious calls for any such action by international bodies or states. In this respect, Indonesia is arguably closer to the Soviet Union, China, and the United States than to any other country.

This book aims to disturb the troubling silence. Its first aspiration is to clarify some basic historical questions: How many people were killed and detained? Who were the victims, and how did they die? Who were the perpetrators, and what motivated them? What happened to the hundreds of thousands who were detained and their families? These basic questions—testament to the significant gaps in our knowledge—need to be answered as a matter of urgency, especially as the number of reliable witnesses and participants declines with every passing year. The book also explores a number of deeper analytic puzzles elaborated below. Most important, it asks the following questions: How and why did this extraordinary violence happen? What have been the consequences of the violence for Indonesian society? And why has so little been said or done about it in the intervening years?

With a few exceptions, scholars have viewed the events of 1965–66 as distinctively Indonesian, explicable mainly in terms of Indonesian culture, society, and politics. The implication has been that the dynamics at play are somehow unique and not comparable to other cases. While there is certainly much that is distinctive about the Indonesian case, my sense is that it shares many features with other instances of mass killing and detention, and that a more broadly comparative approach would be productive, both for understanding Indonesia’s experience and enriching the general debate on such questions. And so while focusing substantively on Indonesia, this book also seeks to engage wider debates about the dynamic of mass killing and incarceration, about the long-term legacies of silence and inaction in the aftermath of violence, and about the history of human rights. To that end it asks: Under what conditions are mass killing and incarceration most likely to occur? Why are some such serious crimes remembered, condemned, and punished, while others are forgotten and left unpunished? What are the political, social, and moral ramifications of such acts and silence—for victims, for perpetrators, and for a society as a whole? My expectation is that a close examination of the mass violence of 1965–66 in Indonesia will provide insights into all these questions.

The Story in Brief

The immediate trigger—by some accounts, the pretext—for the violence came on October 1, 1965. Early that morning, six senior Indonesian Army generals and one lieutenant were detained and then killed by a group of lower-ranking officers belonging to a group called the September 30th Movement (Gerakan 30 September, or G30S). The movement claimed that it had acted to prevent a planned coup d’état by a CIA-backed “Council of Generals” and that it remained loyal to President Sukarno. Ignoring those claims, the surviving army leadership, led by Major General Suharto, insisted that the movement had been masterminded by the PKI, and began a campaign aimed at destroying the party and forcing President Sukarno, whom they regarded as too sympathetic to the PKI, from power. By mid-1966 Sukarno’s authority had been gravely diminished, the army had effectively seized power, the PKI and all leftist organizations had been decimated, and Marxist-Leninist teachings had been formally banned.

The army leadership used a variety of strategies—political, judicial, and military—in its assault on the Left. Within days of the alleged coup attempt, for example, it set in motion a sophisticated propaganda campaign blaming the PKI for killing the generals, accusing it of attempting to seize power by force, and calling on the population to assist the army in crushing the traitors “down to the very roots.” The most important strategy by far, however, was a campaign of violence that entailed outright killing as well as mass detention, ill treatment, torture, and rape. There were distinctive patterns to that violence that when taken together, point strongly to the army leadership’s central role in its planning and implementation.

There were broad commonalities, for instance, in the manner of arrest, interrogation, and execution. Most victims were first arrested without warrant by the army, police, or local paramilitaries, and many were subjected to harsh treatment and torture while under interrogation. Following interrogation, they were sorted into three broad categories based on their alleged degree of involvement in the September 30th Movement and leftist organizations. After screening, some detainees were released, some remained in detention, and some were selected for killing. Those targeted for killing were typically transported to execution sites by military vehicle, or handed over to local vigilante and paramilitary groups. Bound and gagged, they were then lined up and shot at the edge of mass graves, or hacked to pieces with machetes and knives. Their remains were often thrown down wells, or into rivers, lakes, or irrigation ditches; few received proper burials. Many were subjected to sexual abuse and violence before and after their killing; men were castrated, and women had their vaginas and breasts sliced or pierced with knives. Corpses, heads, and other body parts were displayed on roads as well as in markets and other public places.

There were also clear patterns in the identity of those arrested and killed. In marked contrast to many other cases of mass killing and genocide, the victims in Indonesia were not targeted because of their ethnicity, nationality, or religion. On the contrary, with only occasional exceptions, they were selected for arrest and killing primarily on the basis of their real or alleged political affiliations. Moreover, while those killed and imprisoned included a number of high-ranking PKI officials, the vast majority were ordinary people—peasants, plantation workers, day laborers, schoolteachers, artists, dancers, writers, and civil servants—with no knowledge of or involvement in the events of October 1. In other words, the attack on the PKI and its allies was not based on the presumption of actual complicity in a crime but rather on the logic of associative guilt and the need for collective retribution.

The perpetrators also shared crucial commonalities. While arrests and executions were frequently committed by the army and police, many were carried out by armed civilians and militias affiliated with political parties on the Right. In such cases, one or more individuals were selected as special executioners—sometimes referred to as algojo. The involvement of such local figures and groups has led some observers to conclude that the violence was the product of spontaneous “horizontal” conflicts among different social and religious groups. As I will elaborate below, that view ignores—and perhaps deliberately obscures—the fact that such groups and individuals almost always acted with the support and encouragement of army authorities. In the absence of army organization, training, logistical assistance, authorization, and encouragement, those groups would never have committed acts of violence of such great scope or duration.

Despite these broad similarities, there were significant variations in the pattern of the killing. Geographically, they were most concentrated in the populous provinces of Central and East Java, on the island of Bali, in Aceh and North Sumatra, and in parts of East Nusa Tenggara. By contrast, they were relatively limited in the capital city of Jakarta, the province of West Java, and much of Sulawesi and Maluku. The timing of the killing was also distinctive. It began in Aceh in early October, and spread to Central Java in late October and to East Java and North Sumatra in early November. In December 1965, a full two months after the alleged coup attempt, the violence finally started in Bali, where an estimated eighty thousand people were killed in a few months. Meanwhile, on the largely Catholic island of Flores toward the eastern end of the archipelago, it did not begin until February of the following year. The violence started to slow significantly in March 1966, shortly after the army seized power, but continued intermittently in some parts of the country through 1968.5 As discussed below, one of the enduring questions about the violence has been how to explain these variations.

FIGURE 1.2. PKI members and sympathizers detained by the army in Bali, ca. December 1965. (National Library of Indonesia)

There was also significant variation in the levels of political detention in different parts of the country, and in the relative levels of detention and killing. For example, it appears that long-term detention was greatest where the levels of mass killing were lowest, such as in Jakarta, West Java, and parts of Sulawesi. The reverse was also true: where the killing was most intense, as in Bali, Aceh, and East Java, the overall levels of long-term detention were relatively low. In other words, long-term political detention and mass killing seem to have been inversely related. One possible explanation for that pattern is that the military authorities in different regions adopted different strategies for implementing an overall order to destroy the Left. In some areas they opted for a strategy of mass incarceration, while in others they chose mass killing.6

Acute political and social tensions were a critical part of the story, too. Some of these tensions were shaped by the Cold War, which fueled and accentuated a bitter split between the Left and Right inside the country. On the Left was the popular and powerful PKI that had roots dating to the early twentieth century. After an impressive fourth-place finish in the 1955 national elections—the last national elections before the alleged coup—the party grew dramatically in size and influence over the next decade. By 1965, it had an estimated 3.5 million members, and 20 million more in affiliated mass organizations—for women, youth, peasants, plantation workers, cultural workers, and other groups. Arguably the most powerful and popular political party at the time, it also had the ear of President Sukarno, increasingly friendly ties with Beijing, and even some support inside the Indonesian armed forces, especially in the air force.

Ranged against the PKI were most of the Indonesian Army and a number of secular and religious parties. The most important and powerful of these were the Council of Islamic Scholars (Nahdlatul Ulama, or NU) and the right wing of the secular Indonesian Nationalist Party (Partai Nasional Indonesia, or PNI). While these groups differed on many issues, they shared a deep hostility to the PKI. Like the PKI, moreover, the parties on the Right all had affiliated popular organizations that were routinely mobilized for mass rallies and street demonstrations—as well as armed militia groups that played a central role in the violence of 1965–66. In short, by 1965, Indonesia was deeply divided, largely along a left-right (or more precisely, communist–anticommunist) axis, and politics was increasingly being played out on the streets by rival mass organizations and their armed counterparts.

These internal divisions were exacerbated by the wider international conflict and heated rhetoric of the Cold War. Although it was an early proponent of nonalignment, by the early 1960s Indonesia was shifting markedly—and in the view of Western states, dangerously—to the left. Between 1963 and 1965, for example, President Sukarno sought increasingly cordial relations with Beijing, launched blistering attacks on US intervention in Vietnam, withdrew from the United Nations, and began a major military and political campaign—called Confrontation (Konfrontasi)—against the new state of Malaysia, which Sukarno claimed had been created by the United Kingdom and other imperialist powers to encircle and weaken Indonesia. For all these reasons, the United States, the United Kingdom, and their allies saw Indonesia as a major problem. Indeed, by summer 1965, US and British officials were convinced that Indonesia was set to fall to the Communists. As CIA director W. F. Raborn wrote to President Lyndon Johnson in late July 1965, “Indonesia is well embarked on a course that will make it a communist nation in the reasonably near future, unless the trend is reversed.”7

Such anxieties were not new. From the late 1940s onward, the US government had worked assiduously to undermine the PKI, and weaken or remove President Sukarno. It did so, for example, by covertly supporting anticommunist political parties in Indonesia’s 1955 national elections, through a covert CIA operation supplying arms and money to antigovernment rebels in 1957–58, and when that operation failed, through a program of military assistance and training designed to bolster the political position of the army at the expense of both Sukarno and the PKI. Under the circumstances, it is perhaps not surprising that the United States and its allies welcomed the army’s campaign against the Left and Sukarno after October 1965. Nor should it come as a great surprise that these and others major powers eagerly assisted the army in that campaign and its seizure of power.

Capturing the heady mood of optimism of the period, Time magazine described the decimation of the PKI and the rise of the army as “the West’s best news for years in Asia,” and a New York Times story on the subject was headlined “A Gleam of Light in Asia.”8 The reason for these jubilant assessments is not hard to discern. In the context of the Cold War and against the looming backdrop of the war in Vietnam, the mass ...