![]()

SECTION 1

Origins: The Eighteenth Century

Uriel Gellman, Moshe Rosman, and Gadi Sagiv

![]()

PART I

BEGINNINGS

![]()

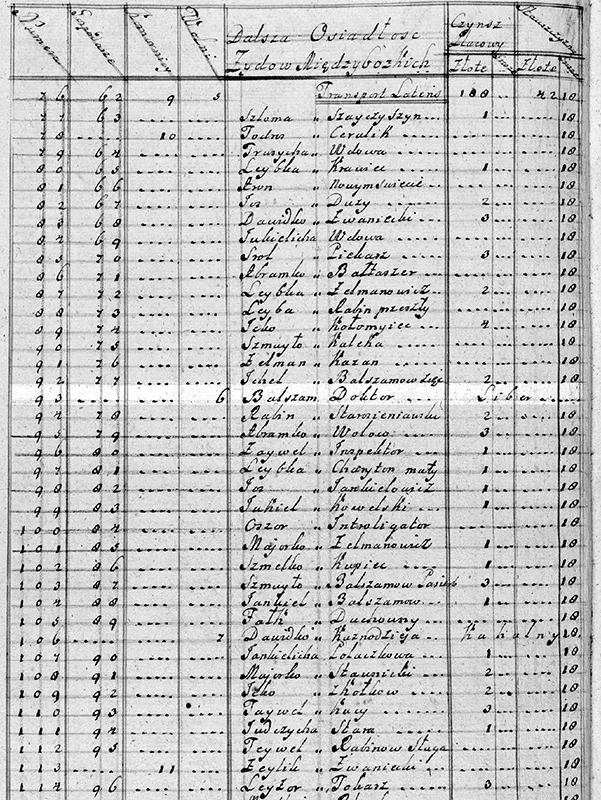

Figure 1.1. A page from August Aleksander Czartoryski’s 1760 register of Jewish residents of Mięzybóż (Mezhbizh) and their property tax (czynsz) obligations. Number 93, paying no tax, is Balszam Doktor...Liber (=Dr. Ba’al Shem...Exempt). One of a few mentions of the Besht in Polish documents, it confirms that he was supported by the Jewish communal establishment, which gave him a tax-free house to live in. Some of the Besht’s relatives and associates also appear in this register. Courtesy of Princes Czartoryski Museum (Laboratory Stock National Museum in Kraków ) (BCzart 8203).

CHAPTER 1

HASIDISM’S BIRTHPLACE

IN 1740, WHEN THE POLISH TAX COLLECTOR surveyed the houses in the town of Mezhbizh, located in the Ukrainian province of Podolia, he found that house 93 had a new resident. The dwelling, owned by the Jewish community council—or kahal—usually housed one of its employees who lived there rent and tax free as part of his compensation “package.” The tax collector did not know the new occupant’s name, but he did know his occupation: kabalista—that is, a Kabbalist. In subsequent years, the tax man referred to him as Balsem, Balsam, Balszam Doktor—all of which are Polish-Ukrainian variations on the Hebrew Ba’al Shem, a “master of the divine name,” who put his esoteric knowledge to work as a healer or, better, shaman. This Ba’al Shem was hired by the Mezhbizh kahal to use mystical and magical rituals to provide his community as a whole and the individuals within it with supernatural security in the quest for health, livelihood, reproduction, and protection from persecution by enemies and demons. Although there were medical doctors who practiced based on classical sources and the more recent, empirically based work of Paracelsus (1493–1541), the meager efficacy of early modern medicine left room for the services of such shamans among Jews and Christians alike.

While ba’alei shem (the plural of ba’al shem) were active throughout Jewish Eastern Europe, the Ba’al Shem in Mezhbizh’s house 93 was no ordinary shaman: he was the Ba’al Shem, Israel ben Eli’ezer Ba’al Shem Tov (the Besht), whom history and legend have crowned as the founder of Hasidism. This first mention of the Besht in Mezhbizh suggests not a wandering folk healer at the periphery of his community, as legend would have it, but, quite to the contrary, someone with an established position within his community and a well-defined role in his world. Morever, this status as communal healer conflicts with the image of the Besht as founder of the Hasidic movement, as a tale in Shivhei ha-Besht (the hagiographical stories about the Ba’al Shem Tov first published in 1814) demonstrates:

A story: When the Besht came to the holy community of Mezhbizh, he was not regarded as an important man by the Hasidim—that is to say, by R. Zev Kutses and R. David Purkes, because he was called the Besht, the master of a good name. This name is not fitting for a pious man (tsaddik).1

What was wrong with a Ba’al Shem serving as a tsaddik, a leader of Hasidim? Were there Hasidim in Mezhbizh before the founder of Hasidism had arrived there? Did these Hasidim not approve of the founder of their movement? How did Israel Ba’al Shem Tov go from popular healer to progenitor of a social-religious movement that was to have an outsized impact on modern Jewish history?

These questions lie at the heart of this chapter of our history of Hasidism. In order to provide answers, we first need to understand the political, economic, social, cultural, and religious world in which the Besht operated. Was this world one of political and economic crisis, as Simon Dubnow first argued, or rather, as we shall claim, an increasingly stable and prosperous one? Were the Jews persecuted and impoverished, or, rather, relatively secure? And was the religious world surrounding the Besht spiritually stunted, as earlier histories have suggested, or already rich in mystical and magical experimentation?

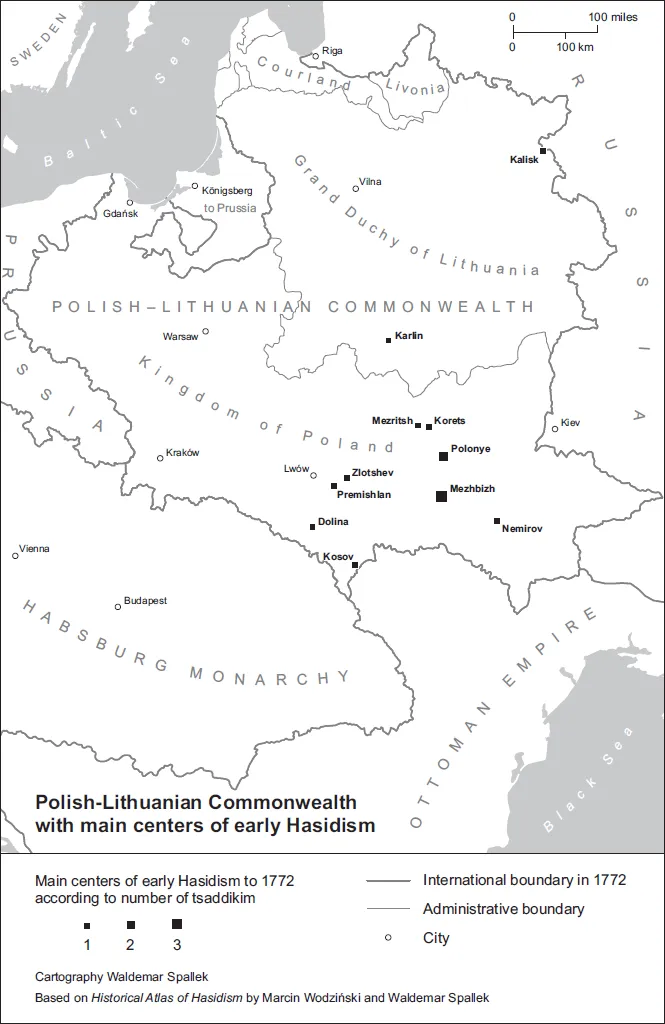

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

We begin some two centuries before the Besht was inscribed on the Mezhbizh tax roles, since it was then that the political confederation arose in which Hasidism was to emerge. In 1569, the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania united into the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita Obojga Narodów—literally, the Commonwealth of Two Nations [Poland and Lithuania]). In common parlance, this is often referred to simply as “Poland.” However, as will become apparent in the course of this book, the political geography denoted by the term “Poland” often changed from one period of Hasidism to another. The country formed by this commonwealth stretched from the Baltic Sea in the north to just shy of the Black Sea in the south and from the Silesian border in the west to beyond the Dnieper River in the east. This was the largest country in Europe west of Moscow. By the end of the eighteenth century, thanks to repeated partitioning and annexation at the hands of its neighbors, Russia, Prussia, and Austria, the Commonwealth ceased to exist. For most of the eighteenth century, however, and in Hasidism’s initial phase until the partition process began in 1772, Poland consisted of today’s Poland, Belarus (White Russia) and Ukraine (up to a line running through Smolensk and Kiev, which both belonged to Russia), Lithuania, and western and southern Latvia (see map 1.1). Of particular interest for the history of Hasidism were the provinces of so-called Right-bank Ukraine (West of the Dnieper) in the southeast corner of the country, especially Podolia, where Mezhbizh was located and the Ba’al Shem Tov was active.

From 1672 until 1699, Podolia had been under Turkish occupation. During that time, usually referred to on the Polish-Ukrainian side of the border as the “ruin,” the Jewish population of Podolia became more diverse, as Turkish, Wallachian, and Moldavian Jews settled in the area. Even after the formal return of the territory to Polish rule, it was known as a refuge for malcontents, heretics, and rebels against the rabbinic establishment. Most prominently, parts of Podolia were home to individuals—some of them rabbis—as well as organized groups that openly declared their fealty to Shabbetai Tsvi, the Turkish Jew who led a messianic movement in the 1660s. Many of these people publicly engaged in Sabbatian rituals, even after Shabbetai Tsvi converted to Islam in 1666 and the mass movement collapsed. It was here that the eighteenth-century messianic pretender, and contemporary of the Ba’al Shem Tov, Jacob Frank, made his career. As will be discussed later, the links between early Hasidism and Sabbatianism are shadowy and elusive, but there can be little doubt that the religious ferment in early eighteenth-century Podolia fertilized the soil in which Israel Ba’al Shem Tov struck roots.

Map 1.1. Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

It is not surprising that a new religious movement could take root in Poland. The Polish state of the eighteenth century was a “Commonwealth of Many Nations”—which meant also of many religions. Approximately 40 percent of its more than eleven million inhabitants in 1760 were ethnic Poles. The rest were Ukrainians (Ruthenians), Belarusians, Lithuanians, Letts, Estonians, Germans, Tatars, Armenians, Italians, Scots, and Jews, each with their own language, customs, and beliefs. Religions included Roman Catholicism, Eastern (“Greek”) and Armenian Orthodoxy, Ukrainian (“Greek”) Catholicism (the Uniate Church), several varieties of Protestantism, Islam, and Judaism. This religious and ethnic pluralism in fact led to a comparatively high degree of religious toleration in Poland, where there was never a war resulting from religious strife, no mass trials of dissidents or mass executions of “heretics.” As we shall see, Jews benefited greatly from this relative toleration.

However, the Protestant Reformation in sixteenth-century Germany threatened the predominant political and economic role of the Catholic Church in Poland, where bishops served in the senate and Church institutions owned large tracts of land. In reaction to the threat of Protestantism, the Polish Catholic Church enlisted the state in criminalizing many sins against religion and the Church as ways of asserting religious control. Transgressions such as adultery, blasphemy, and sacrilege became capital crimes, and the convicted, both Jews and Christians, went to the stake. Jews were subject to the constant threat of desecration of the host charges (so were many Christians), and in particular to blood libel accusations. Thus the underlying tolerance of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was tempered by countervailing forces in the Church, as well as by pervasive folk antisemitism.

Politically, Poland was an early form of limited or constitutional monarchy (although without that explicit name). Political rights were largely limited to the nobility, but in Poland this estate composed up to 10 percent of the population (in England, for example, the nobility was less than 2 percent). There was a bicameral Sejm (diet, parliament), with the upper house consisting of the highest administrative and church officials of each province, while delegates to the lower house were chosen by regional sejmiki (dietines) composed of the nobles of a given area. Polish noblemen took pride in their “Golden Freedom,” meaning that the king was not an absolutist monarch but one whose powers were limited by law. The king could not raise taxes, draft an army, or make appointments without approval by the Sejm. Nobles, however, enjoyed tax and customs exemptions and were the main beneficiaries of lucrative royal land and monopoly grants. Jews in Poland were closely tied to the nobility, and, when Hasidism became established, the courts of the rebbes were sometimes dependent upon noble patronage and even modeled themselves on the courts of the nobility.

The nobility itself was dominated by aristocratic “magnates.” These were twenty or thirty families who owned prodigious landed estates, or latifundia, consisting of huge, often noncontiguous, blocs, each comprising dozens of villages with attached agricultural lands, and any number of towns and even occasional cities. The magnates ruled these latifundia as absolutist grandees holding the power of life and death over their residents and standing at the head of a ramified administrative and judicial apparatus. They also were the owners of all of the natural resources on their lands, controlled tens of thousands of peasants, levied taxes and other duties, afforded privileges granting a measure of self-rule to their private cities and towns, and delegated authority in a variety of ways.

Some 80 percent of the Polish population was composed of peasants who worked the land, owned mostly by the magnates, the king, and the Catholic Church. With the waning of the Middle Ages, the feudal system had largely died out in Western Europe, but in Poland and elsewhere in the East the growth and organization of the magnateowned latifundia in the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries gave it new life and brought about what has been referred to as the “second serfdom.”

Economically, Poland was an agrarian country whose wealth came from below the ground or just above it: crops, mineral mining, forest products, cattle, and dairy products. In the eighteenth century, physiocratic theory promoted land as the real source of value, and labor on it as the only true form of wealth creation, while it denigrated commerce and the merchants who practiced it. Yet the magnates and many city merchants (usually not originally ethnic Poles) carried on a lively international trade, with Poland becoming from the mid-sixteenth century on the breadbasket of Western Europe. In the eighteenth century, however, wars and growing foreign intervention exerted an increasingly deleterious effect on travel and commercial ties. Competition from the New World lessened export demand. Poland’s agricultural products were turned more toward domestic consumption, especially the production of liquor.

Given the sharp polarization of the Polish economy between nobles and peasants, already in the late Middle Ages the Polish nobility began to import foreign groups, notably Germans and Jews, to serve as merchants and in other urban occupations. Since Jews in German lands suffered from repeated expulsions and confinement to ghettos, Poland became an attractive destination, and the Jewish population, which began as a permanent presence in Poland sometime in the twelfth century, grew exponentially from somewhat more than 10,000 around 1500 to approximately a quarter of a million (in a population of 10–11 million) on the eve of the Khmelnytsky Uprising in the spring of 1648.

The Jews played important roles as middlemen in this economy. Jewish economic activity fell into five common areas: moneylending and credit; commerce at all levels (from the country peddler to the town standkeeper and storekeeper, to the regional or international merchant); arenda (leasing of estate income-producing functions); crafts and artisanry; and public service. As Solomon Maimon wrote in his autobiography, a work first published in German in 1791, which is a crucial source on Polish Jews of the eighteenth century:

Figure 1.2. Jan Piotr [Jean-Pierre] Norblin de la Gourdaine (1745–1830), Jewish Musicians, 1778, sepia, 13.9 × 12 cm. A remarkable pen drawing is inscribed by Norblin as “Concert Juif en Pologne.” The scene takes place in a typical tavern, often run by Jews. Property of the Czartoryski Foundation, Krakow, e036922.

[The Jews] engage in trade, take up the professions and handicrafts, become bakers, brewers, dealers in beer, brandy, mead and other articles. They are also the only persons who farm estates in towns and villages [Maimon means the Jews serve as arrendators or income lessees] except in the case of ecclesiastical properties.2

Jews were particularly active in the liquor trade that now consumed increasing amounts of Poland’s production of grain (see figures 1.2 and 1.3).

The weakness of the eighteenth-century Polish state owed much to wars during the previous century. The period of instability began in the mid-seventeenth century with the Cossack Uprising against Polish rule in Ukraine led by Bogdan Khmelnytsky (1648), which quickly inspired a parallel peasant revolt against the Polish feudal economic regime based on the magnate-owned latifundia. Jews were a main target of the uprising and revolt, and these events were commemorated in Jewish historical memory as Gezeirot Tah-Tat, the persecutions of 1648–1649. This war set off a series of invasions and conflicts lasting through the early eighteenth century.

Figure 1.3. Jan Piotr [Jean Pierre] Norblin de la Gourdaine (1745–1830). “Mazepa,” 1775, etching, 9.2 × 8.5 cm. Ivan Mazepa (1639–1709) was a Ukrainian hero. The model for this likeness was apparently a Jewish factor with the nickname Mazepa. The costume is Cossack style, not Jewish. Courtesy of the Czartoryski Foundation, Krakow, Laboratory Stock XV-R.14705.

During 1648–1649, the first phase of this double revolt, just under half of the Jews of Ukraine (between 18,000 and 20,000 out of approximately 40,000) were killed. Most of the others had fled their homes seeking refuge farther west. During the subsequent Muscovite (1654–1655) and Swedish invasions (1655), it can be assumed that some thousands more lost their homes and even their lives. These traumatic events—in the popular imagination all mostly subsumed under the Khmelnytsky episode, Gezeirot Tah-Tat (the persecutions of 1648–1649)—continued to exert profound psychological and theological effects into the eighteenth century and echoed in the nineteenth and twentieth as well. The reading of chronicles written to document and commemorate the tragedies took on a quasi-ritual aspect and a fast day was established, the twentieth of the Hebrew month of Sivan, to perpetuate the memory of the troubles.

Since these events continued to be inscribed in later histories of the Jews of Poland, it was assumed that develop...