![]()

The Lifeworld of Muhammad Yusuf

It is grimly ironic that Muhammad Yusuf, one of the most divisive figures in Nigerian history, was born at the start of a decade when Nigeria’s government undertook a quest to rebuild national unity. Yusuf was born in 1970,1 and his future companion Abubakar Shekau was born around 1969.2 In those years, Nigeria’s civil war was ending, and an oil boom was approaching.

Yet for many Nigerians, the promise of the early 1970s gave way to disappointment. Inequality widened. Corruption worsened. Religion became increasingly politicized. The 1980s and 1990s witnessed repeated instances of mass intercommunal violence. Authorities, urging citizens to look to the future and forget the past, chronically failed to enforce accountability. This chapter shows how, after living through these troubled decades, Yusuf and Shekau could come to make statements like “the government of Nigeria has not been built to do justice…. It has been built to attack Islam and kill Muslims.”3

Sources on the early lives of Yusuf and Shekau are thin. One hagiographical account of Yusuf’s early years, purportedly by one of his sons, says that Yusuf first studied Islam under his own father, memorizing the Qur’an by the time he was fifteen years old. “Then he traveled and went around the country seeking knowledge. He was, may Allah have mercy on him, openhearted and deeply acquainted with books, and just as he employed all his time in seeking knowledge, so he employed it also in spreading it.”4 Whether or not this account is true, what seems clear is that both Yusuf and Shekau were born in rural settings, but then they became mobile as young men, developing a growing political and religious consciousness.

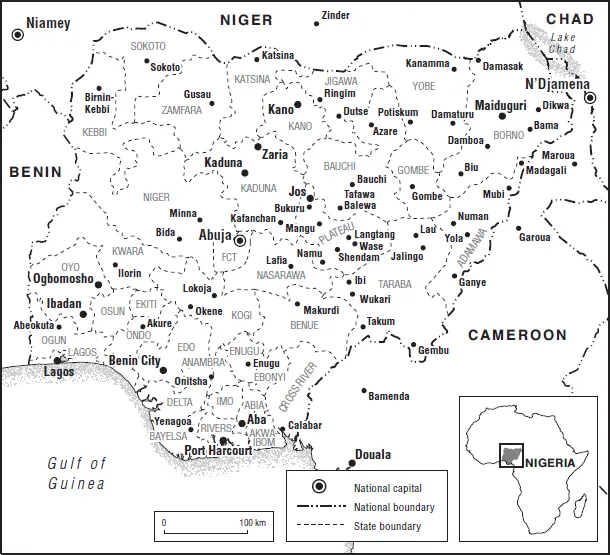

We can tell some of the developments from this period that marked them. First, in their preaching, they would bitterly recall the Muslim-Christian violence that occurred at Kafanchan in 1987 and Zangon-Kataf in 1992. These two towns were far from their homes in geographic terms but close in emotional ones. Yusuf said later that he had been horrified by authorities’ handling of those incidents and others.5 Second, both men would be absorbed, by the eve of the new millennium, by the Salafi current that gained force beginning in the late 1970s. Finally, both men would seize on the deeply felt ambivalence toward Western-style education in northern Nigeria. That ambivalence found voice even in the north’s Western-style universities, where Yusuf may have attracted his first followers.

What we know about Boko Haram’s social base is also limited, but we do know that in early postcolonial northern Nigerian Muslim society, various trends—political, economic, and social—were intertwining with shifts in Muslim identity and politics. What it meant to be a northern Muslim was increasingly up for grabs. This uncertainty, combined with rapid urbanization, altered relationships between elders and youth, patrons and clients, and people and their neighbors.6 These trends were particularly disruptive in the northeast, including in Maiduguri, where Boko Haram later emerged. Young migrants to the city—such as Yusuf and Shekau, who likely arrived in the early 1990s—often encountered poverty and inequality. The poor and the young increasingly drifted beyond the control of the classical poles of religious and political authority: the emirs, the Sufi shaykhs, and the politicians. As part of showing how religion and politics interacted to shape Boko Haram, this chapter argues that Yusuf and Shekau’s revolutionary understanding of Islam reflected the context of political failures, religious fragmentation, and dashed expectations in northeastern Nigeria.

Dashed expectations were acute when it came to education. Successive administrations, regional, state, and national, cultivated false hope about education even as many Muslims remained skeptical about the moral orientation of Western-style schooling. Muslim activists—even many who would later express horror over Boko Haram, and who never promoted violence—increasingly criticized Western-style education starting in the 1970s. In this atmosphere, a rising generation of Muslims was primed to view government and Western-style education with mistrust and even hatred.

A Quest for Unity amid Division

Optimism at Nigeria’s independence in 1960 gave way to tragedy. In the political system of the time, based around three (later four), regions, prominent politicians in the Western and Eastern Regions of Nigeria chafed under the domination of the Northern Region, whose conservative politicians had been closer to the British colonial administration than their more radical southern counterparts. Politics became a winner-take-all affair. The federal government imposed a state of emergency in the Western Region in 1962, targeting opposition politicians there. After the North and its allies swept the elections of 1964–65, they marginalized the major parties of the West and East. In January 1966, junior officers from the Igbo, the largest ethnic group in the East, led a coup. They killed prominent northern Nigerian politicians and sought to undo the northern-dominated political system.

The new military government’s Unification Decree abrogated Nigerian federalism, sparking fears in the north that Igbo domination would follow. Pogroms broke out in northern cities against the Igbo, and northern officers led a successful countercoup. In 1967, civil war broke out. The Igbo-dominated Eastern Region—rebaptized the Republic of Biafra by its leaders—attempted to secede. During the 1967–70 civil war, Biafra was reintegrated into Nigeria at tremendous cost: in addition to military casualties, over a million civilians died of starvation and disease during a blockade.7 Although most of these events occurred far from where Yusuf and Shekau were growing up, the boys’ lives would be shaped in multiple ways by postwar policies.

Authorities’ handling of postwar reconstruction reinforced what was to become a deep-seated pattern in Nigerian political culture: the idea that after collective trauma, looking forward was preferable to looking back. At the war’s end in January 1970, military head of state Yakubu Gowon proclaimed the “dawn of national reconciliation”8 and a policy of “no victor, no vanquished.”9 The civil war was to be forgotten, as were the events that precipitated it. A 1968 pamphlet from the government of North Eastern State, where Yusuf and Shekau grew up, put an optimistic spin on the violent elections, coups, and pogroms of the 1960s: “The events we witnessed prior to and after 1966 can be said to be part of a process in the evolution of an acceptable system of government to our people.”10 This pattern of avoiding accountability, when it was applied to Muslim-Christian intercommunal conflicts in the 1980s and 1990s, would contribute to Yusuf and Shekau’s conviction that the Nigerian state was incapable of doing justice. Yusuf would later express contempt for some of the signature unity-building initiatives of the 1970s, such as the National Youth Service Corps, which assigned college graduates to do service projects outside their home states. Nigeria’s authorities and their Western backers had hoped such initiatives would build “brotherhood [‘yan’uwantaka],” Yusuf said. But, he continued, “God, Glory to Him, the Most High, did not agree, because He had His [own] goal”—replacing the “school of democracy” with Islam.11

In the 1970s, alongside high-flown rhetoric about Nigeria’s “federal character,” there were recurring signals that the country remained profoundly uncertain about what form its government should take. Gowon was deposed in the bloodless coup of 1975, after his promises to restore civilian control had worn thin. Under Murtala Mohammed (1975–76) and Olusegun Obasanjo (1976–79), the military organized a transfer of power back to civilians. Soon, however, the civilian-led Second Republic of 1979–83 collapsed amid regional antagonisms, corruption, recession, and electoral fraud.12 The military regime of Muhammadu Buhari (1983–85) was initially hailed for its effort to restore “discipline,” but it soon lost favor: the economy sputtered under austerity, and Buhari proved authoritarian. Buhari was removed by another general, Ibrahim Babangida. He ruled from 1985 to 1993, manipulating and dividing key constituencies while enriching himself and his circle. Although Babangida initiated a transition of sorts in 1993, the short-lived, nominal Third Republic soon fell prey to General Sani Abacha, who ruled until his death in 1998. Abacha instituted new levels of political repression.13

Nearly all the heads of state from 1960 to 1999 were from the north, but the region’s political dominance did not translate into prosperity or security for ordinary northerners. Amid the many coups and transitions, configurations of power shifted among Nigeria’s elites.14 Yet the system remained an oligarchy.15

Uncertainty and predation also characterized local politics. During Yusuf and Shekau’s youth, Nigeria’s internal boundaries were repeatedly redrawn. Yusuf was born in Jakusko Local Government Area (LGA),16 likely in a village called Girgir.17 His future deputy was born in Tarmuwa LGA, in a village named Shekau—making his name effectively “Abubakar from Shekau.” Until 1967, Jakusko and Shekau villages were part of the Northern Region, but in the military’s administrative reorganization they became part of the newly created North Eastern State. In 1976, another reorganization broke North Eastern State into three smaller units. One of these was Borno State, which at the time contained Jakusko. When Yusuf was twenty-one, a new state, Yobe, was carved out of the old Borno State; Jakusko and Shekau now fell inside Yobe. These repeated administrative reorganizations helped to make local politics more cutthroat.

The recurring pressures for new state creation bet...