- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Souvenir

About this book

Object Lessons is a series of short, beautifully designed books about the hidden lives of ordinary things.

For as long as people have traveled to distant lands, they have brought home objects to certify the journey. More than mere merchandise, these travel souvenirs take on a personal and cultural meaning that goes beyond the object itself. Drawing on several millennia of examples-from the relic-driven quests of early Christians, to the mass-produced tchotchkes that line the shelves of a Disney gift shop-travel writer Rolf Potts delves into a complicated history that explores issues of authenticity, cultural obligation, market forces, human suffering, and self-presentation. Souvenirs are shown for what they really are: not just objects, but personalized forms of folk storytelling that enable people to make sense of the world and their place in it.'

Object Lessons is published in partnership with an essay series in The Atlantic.

Souvenir features illustrations by Cedar Van Tassel

For as long as people have traveled to distant lands, they have brought home objects to certify the journey. More than mere merchandise, these travel souvenirs take on a personal and cultural meaning that goes beyond the object itself. Drawing on several millennia of examples-from the relic-driven quests of early Christians, to the mass-produced tchotchkes that line the shelves of a Disney gift shop-travel writer Rolf Potts delves into a complicated history that explores issues of authenticity, cultural obligation, market forces, human suffering, and self-presentation. Souvenirs are shown for what they really are: not just objects, but personalized forms of folk storytelling that enable people to make sense of the world and their place in it.'

Object Lessons is published in partnership with an essay series in The Atlantic.

Souvenir features illustrations by Cedar Van Tassel

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introduction: An Embarrassment of Eiffel Towers

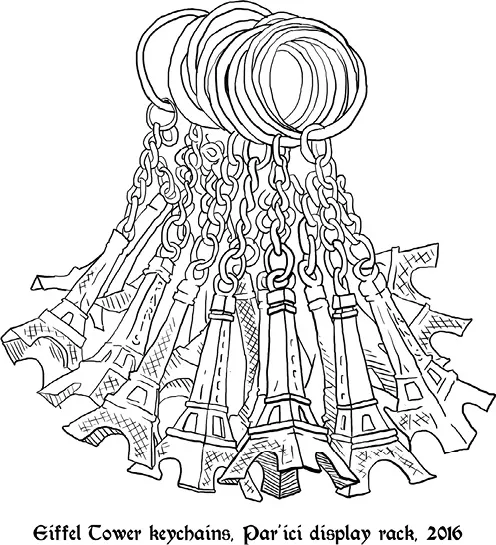

At Par’ici, a souvenir shop located at 52 Rue Mouffetard in Paris, almost every item on offer has something to do with the Eiffel Tower. Here, in 270 square feet of cramped showroom space, with Charles Trénet and Édith Piaf tunes warbling in the background, one can buy Eiffel Tower T-shirts and Eiffel Tower snow globes; Eiffel Tower whiskey flasks and Eiffel Tower oven mitts; Eiffel Tower bottle openers and Eiffel Tower ashtrays. The music boxes here come with Eiffel Towers engraved on the outside; berets come with Eiffel Towers silhouetted in sequins.

For unexpected weather, Par’ici sells Eiffel Tower-themed umbrellas, sun hats, and scarves; for amusement, it sells Eiffel Tower-embossed soccer balls, poker chips, and Rubik’s Cubes. Several dozen types of Eiffel Tower miniatures are also on offer, from inch-high plastic key chains that cost 0.50 euros, to bronze lawn ornaments that stand four-and-a-half-feet tall and sell for 890 euros each. The store also offers a fair selection of items that don’t allude to the Eiffel Tower (Mona Lisa shot glasses, plastic cancan-dancer figurines, ballpoint pens in the shape of baguettes, etc.), but for the most part Eiffel Tower products dominate.

A central irony here is that 52 Rue Mouffetard is not particularly close to the Eiffel Tower. One cannot glimpse the Tower from any point along this cobblestoned thoroughfare, and a pedestrian would need to walk west for one hour to reach the monument on foot. It is because of this seeming anomaly—not in spite of it—that Par’ici feels like a fitting place to begin our investigation of souvenirs.

In French, the word souvenir is commonly used as a verb, and means “to get back to myself,” or “to remember” (from the Latin subvenire, “to come to mind”). In English “souvenir” is a noun—an object through which something (a place, a person, an experience) is remembered. This English definition dates back to the 1700s, though it didn’t come into widespread use until the late nineteenth century—about the same time mass-market travel gift shops first began to pop up in places like Paris.

I’ve been teaching creative writing at the Paris American Academy each summer since 2002, and I often pass by Par’ici on my way to or from school. Rue Mouffetard, an Ernest Hemingway haunt back in the 1920s, is a lively pedestrian street full of atmospheric restaurants and cafés. Though popular with tourists during the summer months, Rue Mouffetard is not, by Paris standards, a major tourist area. Nonetheless, Par’ici is one of two shops plying the souvenir trade along this short thoroughfare. Its competitor, Obj’Ai Trouvé, located just seven storefronts away, also features an abundance of Eiffel Tower-themed trinkets.

Both of these stores sit in the heart of the city’s Fifth Arrondissement, a one-square-mile Left Bank district that, at the time of this writing, is home to thirty-three distinct tourist-market gift shops (with names like Au Chic Souvenir, Paris Smile Souvenirs, Paris Star Souvenirs, Rose for You, and Gift Paradise). More than a dozen Fifth Arrondissement newsstands also sell tourist knickknacks, as do museum shops in the Jardin des Plantes and the Musée national du Moyen Âge. Add in the souvenir items on offer at the various antique stores, bookshops, jewelry boutiques, and art galleries—as well as the green-box bouquinistes vendor-stalls along the Seine—and one can scarcely walk three blocks in the Fifth Arrondissement without being presented with dozens of souvenir-buying options.

This is all more remarkable for the fact that the Fifth Arrondissement isn't among the top five tourist districts in Paris—not when compared to the First (home to the Louvre and the Tuileries), the Fourth (the Notre Dame and the Pompidou), the Eighth (the Champs-Élysées and the Arc de Triomphe), or even the Eighteenth (Montmartre and Sacré-Cœur). The Seventh Arrondissement features the Eiffel Tower itself, which attracts so many souvenir vendors that a 2011 attempt to evict unlicensed salespeople from the area required a deployment of riot-control police (three of whom were injured when the besieged tchotchke-peddlers began hurling rocks and bottles). The following spring French customs police busted the street vendors’ Paris-based ringleaders, seizing 13 tons of unlicensed miniature Eiffel Towers in the process.

When I first learned of this—13 tons of contraband Eiffel Tower kitsch!—I found it hard to believe that Par’ici, a shop three miles away, in a much quieter part of the city, could stay in business. Eventually curiosity got the best of me, and I introduced myself to the store’s 59-year-old owner, Désirée Taieb, who runs Par’ici with her son Sebastian. Her shop, she told me, dates back to 1992, and she set it up with the help of her sister, who peddles similar merchandise just up the block at Obj’Ai Trouvé. Désirée has, in the past, dabbled in more traditional fare (such as handmade porcelain dolls in French peasant costumes), but ultimately tourists are more inclined to buy mass-produced bijouterie. “We sell Eiffel Tower things,” she told me, “because people want Eiffel Tower things.”

*

While Paris is one of the most heavily touristed cities in the world, the market for travel souvenirs has also seeped into the planet’s most desolate and remote corners—a fact I was reminded of during a recent journey to Namibia’s Skeleton Coast in southwestern Africa. This desert-parched, rock-strewn stretch of Atlantic coastline south of the Angolan border has an end-of-the-earth feel; sixteenth-century Portuguese sailors called it "The Gates of Hell," while Namibian Bushmen called it "The Land God Made in Anger." Apart from a smattering of picturesque sand dunes and scientific research outposts, the only tourist draws here are the bleached whalebones and rotting shipwrecks that litter the coastline. Still, it is difficult to drive the length of the Skeleton Coast without spotting a few Damara tribesmen selling polished rocks along the roadside.

By African souvenir standards, polished rocks are something of a novelty. Visit any tourist-town craft bazaar in southern Africa—in the Namibian coastal resort of Swakopmund, for example, or in Cape Town’s sprawling Pan-African Market—and the offerings are consistent to the point of being standardized. Much like Parisian gift shops focus on Eiffel Towers and Mona Lisas, African souvenir-market stalls carry some combination of hardwood serving bowls, safari-animal figurines, tribal-ceremony masks, beaded bracelets, engraved ostrich eggs, warthog-tusk bottle openers, and hand-dyed batiks. Ask African market-vendors why these particular items are on sale, and you’ll get an answer similar to the one I got in Paris: years of trial and error have shown that these objects—which evoke a romanticized, if faintly generic, vision of the African continent—are what tourists want.

Curiously enough, market demand is also what has drawn Damara rock vendors to the forlorn highways of the Skeleton Coast. Historically, the Damara were among the original inhabitants of what has now become Namibia, and their Khoekhoe language features clicking sounds distinctive to the region. The arrival of powerful Bantu-speaking tribes (and, later, German colonialists) in the nineteenth century pushed the Damara out of their traditional hunting and grazing regions and into a desolate, mountainous area in the northwestern part of the country. Though water was scarce in this part of Namibia, the mountains yielded semiprecious stones—turquoise, amethyst, garnets, tiger’s eye, tourmaline—that were prized by German and Afrikaans settlers. The stone trade proved so profitable that the Damara, who had typically lived as subsistence pastoralists, began to travel out of the mountains to sell rocks along Namibia’s major roadways. As the country’s tourist infrastructure grew over the course of the twentieth century, the roadside rock trade grew with it.

I learned all of this from Johannes !Hara-ǀNurob, a 41-year-old Damara elder who hawks semiprecious stones on a beach near the Zeila shipwreck, thirty-five miles north of Swakopmund. Though Johannes plies his trade more than seven thousand miles away from Paris, his no-nonsense pragmatism reminded me of Désirée Taieb and Par’ici. Shipwrecks are major tourist attractions along the Skeleton Coast, so when the Zeila (an Angolan fishing boat) ran aground here in 2008, Johannes was one of a dozen Damara vendors who turned up to sell rocks to sightseers. The Damara work the beach in teams of three, taking turns as each new tourist car arrives; on a good day, a three-man team can split $50 worth of sales—though it’s not uncommon to sell no stones at all when tourist traffic is light. Johannes and his colleagues live on the beach near the Zeila full-time between November and February, returning in the off-season to their home villages, where they spend time with their families, raise cattle, and dig for more rocks up in the mountains.

When I asked Johannes what traditional Damara life was like before the stone trade, he told me that he wasn’t sure—that, for him, Damara tribal identity is inseparable from selling souvenirs. “For as long as white people have been coming to Namibia we have been selling them rocks,” he said. “My father sold rocks, and my grandfather too; I grew up doing the same. To me, this is traditional Damara life.”

*

I should probably point out that the very definition of what constitutes a souvenir can be a slippery concept. Some people who buy, say, a chunk of rose quartz from Johannes on the Skeleton Coast might display it back home as a reminder of Namibia; others might resell it at a profit without taking much interest in what it represents at a personal level. On that same token, many people collect non-travel objects—mementos, keepsakes, heirlooms, trophies, antiques, memorabilia—that have souvenir-like qualities while not being souvenirs in the literal sense. In the interest of simplicity, I’m going to focus on objects that are collected for personal reasons during the course of a journey.

Academic researchers have pinpointed five different categories of souvenirs that people seek out in their travels. The stones sold by Johannes and other Damara vendors in Namibia are considered “piece-of-the-rock”—physical fragments of the travel destination or experience itself. This time-honored souvenir category encompasses everything from pebbles and seashells, to ticket stubs and emptied wine bottles. Usually this type of souvenir is found or kept at no extra cost, though (as is the case with Namibian turquoise, Latvian amber, or chunks of the Berlin Wall) it is sometimes collected and sold by enterprising vendors. A second souvenir category, “local products,” includes everything from Uruguayan leatherwork, to Mozambican piri-piri sauce, to the Parisian fashion designs found in the boutiques along Rue Mouffetard.

While these first two souvenir types predate the tourism industry, the final three souvenir categories encompass the mass-market objects one finds in places like Par’ici: “pictorial images,” which includes postcards and posters depicting local iconography and attractions; “markers,” which includes T-shirts, coffee mugs, and other products branded to the location; and “symbolic shorthand,” which includes miniaturized Eiffel Towers and Notre Dames. Since these three types of souvenirs can be manufactured in bulk and shipped most anywhere within the globalized economy, they tend to represent just how abstracted the relationship between souvenir and place has become in the twenty-first century.

In Par’ici, for example, Désirée has set out small signs indicating specific items that were made in France—but this only underscores the fact that a majority of the souvenirs sold here (and indeed in most Paris gift shops) were manufactured in distant Chinese factories. Moreover, thanks to Désirée’s tech-savvy son Sebastian, one need not even visit Paris to purchase these souvenirs, since the Par’ici website, souvenirparis.com, features an online store that includes international shipping, a blog with virtual tours of the city, and a link to the store’s Instagram account (@souvenirparis, which boasts more than 10,000 followers from around the world).

When one ponders the prospect of going online and ordering a Guangzhou-made miniature Eiffel Tower and having it shipped from Paris to Dubuque without the need to set foot in France, it is tempting to write off the souvenir ritual as an exercise in postmodern absurdity. Yet, while each Eiffel Tower tchotchke displayed on the shelves of Par’ici enters the store with generic commercial value, it exits the store as part of an individualized narrative (even when Sebastian wraps it up and mails it to a place like Iowa). Like all souvenirs, the object’s personal meaning gains potency as it moves away from the place that imbues it with objective meaning.

In a sense, souvenirs are a metaphor for how lived experience can endow most any object with personal significance. To understand how even mass-produced kitsch can become rich with meaning to the traveler who collects it, we must first hearken back to the earliest recorded journeys, when travel was difficult, and the objects one collected on a journey were considered sacred.

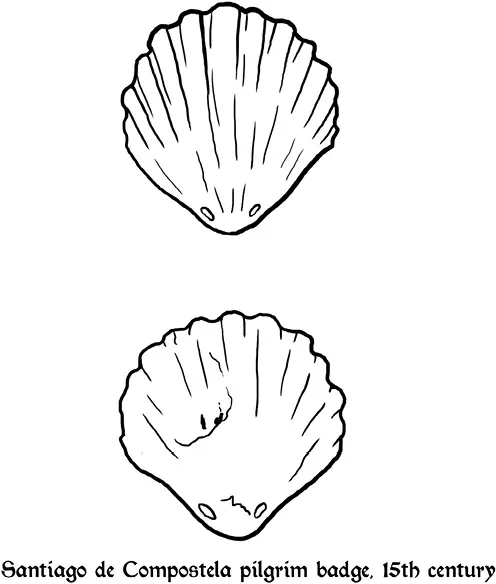

2 Souvenirs in the Age of Pilgrimage

As Christian pilgrimage to the Holy Land became fashionable in the centuries following the Crucifixion, pilgrims’ enthusiasm for sacred souvenirs began to create problems for the custodians of Jerusalem’s shrines. On the Mount of Olives, for example, the main pilgrim attraction was the Sanctuary of the Ascension, built to commemorate the Gospel account of Christ’s final moments on earth before departing into heaven. To underscore the drama of this miraculous moment, a portion of the sanctuary floor had been left unpaved, and tradition asserted that the footprints of Jesus could still be discerned in the exposed dirt. Eager to possess a bit of the dust that had touched the messiah’s feet, visiting pilgrims began to spirit away fistfuls of the sanctuary floor in such profusion that the shrine’s caretakers were forced to haul in fresh dirt every few weeks.

In some ways modern tourism in the West traces back to the Christian rite of pilgrimage, which was the primary form of personally motivated, nonmilitary, noncommercial travel in the Middle Ages. Granted, some core aspects of pilgrimage (the months of walking, the constant fear of illness and death) don’t factor much in a modern jet vacation—but there is a sense in which both experiences serve to validate the existence of a distant, once-imagined reality. In this sense, buying an Eiffel Tower key chain in Paris carries faint echoes of the pilgrim’s impulse to pilfer dirt from the Sanctuary of the Ascension. “People feel the need to bring things home with them from the sacred, extraordinary time or space, for home is equated with ordinary, mundane time and space,” scholar Beverly Gordon observed. “They can’t hold on to the non-ordinary experience, for it is by nature ephemeral, but they can hold on to a tangible piece of it, an object that came from it.”

No doubt the impulse to make faraway places tangible by collecting objects predates recorded history. One imagines an ancient hunter collecting shimmering stones from a distant mountain to share with his children back home, or an ancient gatherer bringing her husband exotic flowers from a berry-picking excursion in an unfamiliar valley. The earliest tribal religions attributed supernatural powers to objects, and oftentimes these devotional “fetishes” were in essence travel souvenirs—items that were imbued with an aura of magic by dint of their larger-than-life foreignness.

Some of the earliest recorded travel-souvenir objects were gifts brought home from cross-cultural journeys. When Prince Harkhuf of Egypt traveled to Sudan around 2200BC, for example, he collected leopard...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Series

- Title

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Introduction: An Embarrassment of Eiffel Towers

- 2 Souvenirs in the Age of Pilgrimage

- 3 Souvenirs in the Age of Enlightenment

- 4 Interlude: Museums of the Personal

- 5 Souvenirs in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

- 6 Souvenirs and Human Suffering

- 7 Souvenirs and (the Complicated Notion of) Authenticity

- 8 Souvenirs, Memory, and the Shortness of Life

- Selected Sources

- Index

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Souvenir by Rolf Potts,Cedar Van Tassel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.