eBook - ePub

Strategic Management in Emerging Markets

Aligning Business and Corporate Strategy

- 335 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Strategic Management in Emerging Markets

Aligning Business and Corporate Strategy

About this book

Traditionally, analysis of strategic management has divided the focus between a business and corporate level. This text goes beyond that to help readers recognize the interplay of the "how" and "which" of strategy. It embraces the integrated nature of learning to avoid the compartmentalization of strategy concepts.

Strategic Management in Emerging Markets: Aligning Business and Corporate Strategy has three uniquely valuable components. First, it identifies and integrates corporate and business strategy levels along with their co-evolution; enabling readers to better understand strategic alignment. Secondly, there is an explicit presentation of strategy for emerging markets which utilizes original theory and cases to help readers to better identify and succeed in high growth business contexts. Thirdly, it presents an integrative and comprehensive case study of an international corporation, Inchcape Inc., which is designed specifically to facilitate cumulative and holistic learning.

The book focuses on newer aspects of strategy theory and the hallmarks of emerging markets, such as dynamic capabilities, environmental turbulence, and the difficulties associated with strategic choice and execution in complex business environments. An appreciation of the role of megatrends is also a key aspect since emerging markets evolve at much faster rates than slower growth developed economies. Appealing to practitioners and students of strategic management and international business, the book bridges conceptual and practical realms of strategy generating intellectual synergies for the reader and enhancing the learning experience.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Strategic Management in Emerging Markets by Krassimir Todorov,Yusaf H. Akbar in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Strategy for the Emerging Markets

Much emphasis in recent years in the boardrooms of companies large and small has been the growing importance of high-growth developing economies, called emerging markets, in achieving strategic growth objectives. Emerging markets demonstrate core characteristics that differentiate them from developed economies and those developing economies that have not been able to grow at sufficient speed to attract the attention of business strategists. Faced with persistently slow economic growth at home, and the progressive saturation of their traditional foreign markets in other developed economies, firms from developed countries have substantially ramped up their strategic efforts in emerging markets. This chapter explores strategy development in the context of emerging markets. The main emphasis of the chapter is in which areas business strategy needs to be adjusted and modified to respond to the specific economic, institutional, and social features of emerging markets. The chapter begins with a brief discussion of the concept itself. The chapter then provides a detailed view of economic, institutional, and social features of emerging markets. Section 2 dives into the specific posture and configuration of business strategies in emerging markets by dividing them into three discrete segments: Tier 1, Tiers 2–3, and Tiers 4–5. These tiers are segmented on the basis of income. Section 3 then offers a detailed set of guidelines on strategic and tactical considerations for each of the tiers. Section 4 is a short concluding section.

What are the specific characteristics of emerging markets that have attracted so much attention from multinational firms? First, is that the economic growth rates of these economies outstrip the world average growth rate and are certainly higher than those of developed economies. Second, rates of human development such as access to health care, sanitation, infrastructure development, and increasing literacy are improving rapidly and converging with developed economies. Third, emerging market governments have typically committed their societies and economies to participate in liberalization efforts associated with trade and investment. The speed of liberalization varies country by country. For example, the former centrally planned economies of Central and East Europe rapidly liberalized with most of them joining the European Union by 2007 – less a generation after the 1989 collapse of central planning. By contrast, Brazil, China, and India have pursued more selective liberalization policies that centered closely on their interest in maximizing the potential for technology transfer from foreign investors as well controlling the business conduct of the inward investors. Fourth, there is a broad range of income strata in these economies suggesting that strategies for emerging markets can vary considerably depending on the income strata targeted. Fifth, some of the emerging markets have population sizes that are huge. This presents unique challenges for scaling for firms in these markets.

All told, the aforementioned five characteristics suggest that much of what strategists would argue for in developed economies may not be as relevant for emerging markets. This chapter is an exploration of why we may need to reconsider our strategy models, frameworks, and action plans for emerging markets. The chapter focuses on three key issues: First, any of the business and economic institutions that form the foundation of support for the development and execution of corporate strategy are either weak or nonexistent in emerging markets. Examples of such institutional voids (Khanna & Palepu, 1997) include an absence of enforceable patent laws, as well as a shortage of consistent and credible business information services such as consulting firms. Institutional voids moderate the effectiveness of strategic capabilities and resources possessed by firms reducing the value of their sources of competitive advantage. Second, with institutional voids comes greater market and technological uncertainty. This increases the value of dynamic capabilities (Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997) in the configuration of corporate strategies with a higher emphasis on strategic agility and a greater discounting of the value of corporate planning in emerging markets (Teece et al., 1997). Third, while a central tenet of business strategy is that differentiation is a more sustainable strategy relative to pursuing price-sensitive, low-cost strategies, in emerging markets this may not hold. This relates specifically in targeting lower-income customers in these developing contexts. As discussed in the following text, while innovation as a source of differentiated advantage will typically be associated with increasing product or service sophistication, in price-sensitive emerging market segments, firms should emphasize innovation simplifies complex products and services, lowering prices, such that low-income customers can afford them.

This chapter is organized as follows. Part 1 considers the emerging market context from an economic, institutional, and social perspective. Part 2 elaborates on the argument that there are three distinct “markets” within emerging markets building on the base of the pyramid work of C. K. Prahalad and Stuart Hart that necessitate three distinct corporate strategies. Part 3 explores in detail these three strategies. In brief, the first strategy is largely the same ones that are pursued in developed economies yet are adjusted to respond to local differences such as language and culture. The second emphasizes scaling, cost efficiencies, and affordability while the third has an enhanced role for shared value (Porter & Kramer, 2011) and social entrepreneurship. Part 4 is a concluding section that sets the scene for further chapters in the book.

Emerging Markets: Key Features

Antoine W. van Agtmael was deputy director of the capital markets department of the World Bank’s International Finance Corp. (IFC) at the time he used the phrase “emerging markets” for the first time at a business conference in Thailand in 1981. Since then, it has entered the lexicon of management and strategy as much an imperative as a descriptor. It’s important to emphasize that in the same way that global strategy became a strategic imperative in the 1980s for executives around the world, at the turn of the twenty-first century a similar imperative was heralded in the boardrooms of multinational firms called ‘BRIC strategy.” In a manner similar to Agtamael’s use of emerging markets, BRIC was coined by the then Chief Economist at Goldman Sachs, Jim O’Neill, to lump together Brazil, Russia, India, and China as the most important economies for companies to target. This expanded into an “emerging market strategy” as other countries such as Indonesia, Mexico, Vietnam, and Turkey entered the business consciousness of executives. Thus today, no ambitious company can produce an annual report without expressly addressing the issue of emerging market strategy. Given this intensified interest, it is both analytically useful and strategically relevant for us to explore exactly what are the key characteristics of emerging markets? We will divide these into economic, institutional, and social factors.

Economic Components of Emerging Markets

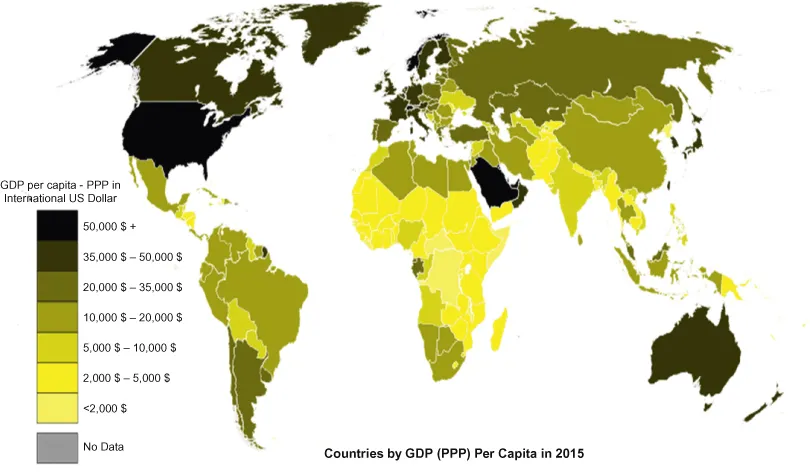

In the last decade, emerging markets came to represent 86 percent of the world’s population, 75 percent of the world’s land mass and resources and accounted for 50 percent of world GDP at purchasing power parity (PPP) (Watt et al., 2011). Figure 1.1 shows GDP PPP for emerging markets compared with developing economies. There is a clear “North”–“South” divide in the current figures. When we examine growth rates, what is evident is a that there is discernible and persistent growth gap between developed and developing economies in the range of 2 percent. The International Monetary Fund found that from 2006 to 2013, incomes have steadily risen in developing countries at an average annual rate of 6.4 percent. In 2014, these same economies generated over USD 10,000 of GDP per capita, a significant increase from USD 3,200 and USD 5,300 just 20 and 10 years ago, respectively. The IMF further predicts that GDP per capita is expected to increase to USD 13,800 by 2020 (International Monetary Fund, 2014).

Figure 1.1. Countries by GDP (PPP) in 2015. Source: Wikipedia CC0 1.0; Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Countries_by_GDP_(PPP)_Per_Capita_in_2015.svg.

As we discuss in later chapters, strategic growth is easier to achieve when markets are growing rather than being stagnant or contracting. Managers find it much harder to take market share from their competitors’ existing clients rather than finding new customers for reasons of switching costs such as contracting, brand loyalty, and so on. Seen through this lens, emerging markets are an attractive option for firms.

Urbanization is rising fast in developing economies. According to United Nations (2014), the urban population in emerging markets is expected to rise to about 3.7 billion by 2025. By 2030, city populations in emerging markets are likely to be composed of 4 billion people, or about four times the size of urban populations in developed countries. Urban populations present multiple business opportunities for firms. They typically consume more monetized consumption (services, leisure, medical etc.) relative to rural populations and, in general, are easier to reach, given that they tend to be more densely populated.

Da Rita (2017) suggests that between 2017 and 2020, USD 4.5 trillion per year will be spent on infrastructure in developing economies (Da Rita, 2017). This presents two strategic opportunities for firms: first, a range of firms from sectors, which participate in infrastructure development, will have new business opportunities to compete for the tenders published by governments in developing economies. Second, as infrastructure improves in developing economies, both physical and digital distribution systems should allow for a greater amount of goods and services being made available to consumers and enhancing the business opportunities for firms across the entire economy.

While middle-income population segments in emerging markets remain typically smaller than in developed economies, the growth of “middle classes” is an important feature of market opportunities for firms (Kharas, 2010). Typically “middle classes” spend more of their disposable income on higher priced forms of consumption and durable products. They also tend to be more brand conscious than lower-income consumers (Mukherjee, Satija, Goyal, Mantrala, & Zou, 2012).

Another salient feature of economic features of emerging markets is the degree of economic diversification in the country. It is largely axiomatic that diversified economies produce more reliable and durable economic growth since they can be insulated against shifts in fortunes in specific industries. Developing economies that rely upon a narrow range of sectors for economic growth such as natural resources or agriculture struggle to maintain high enough economic growth rates to drive convergence with develop countries. This is for two reasons: first is because of the cyclicality of commodity prices related to economic growth in developed economies and second is the long-term rise in price elasticity for commodity products as substitutes for natural resources are found. The most dramatic illustration of this is the case of Argentina that at the turn of the twentieth century was one of the more prosperous countries in the world driven largely by exports of agricultural and natural resources. A century later, Argentina’s economic fortunes have hardly advanced since then.

Lastly, the extent to which emerging markets have joined international economic integration agreements on a global and regional level is an important consideration for firms. The fact that most economies in Central and East Europe have joined the EU has created a level playing field for foreign investors and enhanced the capacity for these firms to compete on the basis of their sources of competitive advantage more effectively. In fact, joining the EU for Central and East European countries represented one of the most important attempts at formal institutionalization of their economies in their history. It also implied wholesale regulatory convergence (Akbar, 2003). The issue of institutional aspects of emerging markets is now dealt with in the following section.

Institutional Aspects of Emerging Markets

In developed economies, institutions that support markets are treated largely as background conditions for firms. For example, they build strategies on the assumption that intellectual property laws are enforceable, that courts are transparent, that business intelligence data are readily available, and that banking infrastructure exists to allow clients to buy products or services. One of the benefits of economic institutions for firms is that long-established institutions facilitate the creation of mechanisms for aggregating and exchanging knowledge that can be used to formulate and execute strategies. Institutions serve to ensure that firms can learn more quickly about business environments and avoid redundancy of effort. The ability to synthesize existing knowledge with new knowledge is a key source of dynamism for firms and the presence of business institutions allows firms to combine existing knowledge with new knowledge gathered in the new market is vital. A recent example serves to illustrate this challenge. When US’ largest PC seller, Dell Corporation, entered the China market, it struggled to gain traction against local retailers. For example, in 2002–2003, Dell lagged behind in fourth place with just 6 percent of the China market (Einhorn, Larson, & Ricadela, 2003). This was largely due to Dell’s innovation in its developed markets – the direct sales model. This business model required two features to be successful: first was |Internet access for customers to configure and buy their PCs and second was access to a credit or debit card to make the payment online. In 2002–2003, few Chinese clients had credit/debit cards and while Internet access was available, it was far from common to be found in Chinese homes where most PCs were purchased online by customers. Thus, the absence of key supportive institutions largely taken for granted in developed economies was missing in China at that time. This drove a fundamental change in Dell’s retail strategy for China. Rather than relying on consumer PC sales, Dell switched its efforts to focus on higher priced corporate hardware such as servers avoiding the institutional weaknesses of retail PC market in China. Later on, Dell signed agreements with Chinese supermarkets to set up “kiosks” where customers could order their PCs in-store. They also developed a cash-on-delivery option for clients who didn’t have a credit card as long as the customer paid a deposit at the time of ordering. This example provides clear evidence of the need of strategic model re-engineering required by firms which enter emerging markets.

The absence of institutions in emerging markets has been termed Institutional Voids (IVs). IVs relate to “unfamiliar conditions and problems” (Arnold & Quelch, 1998, p. 8), which characterize emerging markets and can deter firms from entering, and curb their growth into those markets (Jansson, 2007). According to Khanna and Palepu (2010, p. 6), “Ideally, every economy would provide a range of institutions to facilitate the functioning of markets, but developing countries fall short in a number of ways. These institutional voids […] are a prime source of the higher transaction costs and operating challenges in these markets” (Khanna & Palepu, 2010).

IVs imply the absence of numerous supporting features of developed economies some of which are public institutions and others developed and maintained by private sector entities. First are credibility enhancers such as credit rating agencies that can provide reliable data on the performance of financial assets and securities. This could be very important in the future valuation of investments in emerging markets. Second are information analyzers and advisors which refers to audit, consulting, and legal services firms which can provide credible advice on how to develop and execute market entry and growth strategies. Third are aggregators and distributors – these are typically firms who provide logistics infrastructure to bring goods to market at both wholesale and retail levels. Developed economies typically have integrated distribution and logistics systems whereas developing countries suffer from fragmentation and technology backwardness in logistics and distribution. Fourth, transaction facilitators relate to both public and private institutions. They are typically focused on financial transactions such as payments systems; regulators and adjudicators come from both the public and private sector and can include industry specific institutions related to such issues as professional certification. They can also include economy-wide regulators as well such as health and safety standards.

As much as institutions exist on a formal basis, there is also the issue of institutional norms and implementation. Norms refer to practices and active enforcement of institutional laws and processes – often not codified in law. In emerging markets, there may be formal institutions in place but a combination of lack of resources, weaknesses in professionalization of staff, and corruption mean that de facto implementation of rules and practices is also weak, so firms need to be conscious of the fact that even if institutions exist on a formal basis, they shouldn’t take for granted that they can be enforced.

Social Aspects of Emerging Markets

The economically fragile nature of emerging markets has profound impacts on social aspects of these communities. Poor or nonexistent access to basic economic goods; grave social depravations such as poor housing, education, and sanitation; as well as dysfunctional and corrupt public institutions place heightened emphasis on socially sustainable business strategies in emerging markets. Both perceptions and realities of multinational firms that they invest in developing economies to exploit low labor costs and weak regulatory environments are pervasive. Since many of the people in emerging markets are poorly positioned to defend their socioeconomic interests, especially resisting pressures for conspicuous consumption, firms operating in these communities must reassess how they deliver profitability for their shareholders.

The United Nations’ Human Development Index (HDI) measured on a scale of 0 to 1 is an aggregate of three indicators: longevity, knowledge, and the command over resources needed for a decent life. For longevity, the index measures life expectancy at birth. Adult literacy and years of schooling are a proxy for knowledge. Command over resources is measured by adjusted GDP per capita. In Figure 1.2, there are emerging markets compared with developed economies. The HDI has four categories: very high, high, medium, and low development. The ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- 1 Strategy for the Emerging Markets

- 2 Basics of Strategy

- 3 Basics of Strategic Management

- 4 Corporate and Business Strategy

- 5 Contemporary Corporate Strategies

- 6 Strategic Paradigms

- 7 Generic Strategies

- 8 Business Models and Strategy

- Bibliography

- Index