![]()

Glass/Ware: New Media for Writing American Lives

CENTER FOR INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES OF WRITING / 2002

Multimedia presentation, February 18, 2002. Reprinted with permission of the Center for Interdisciplinary Studies of Writing, University of Minnesota and Lillian Bridwell-Bowles.

Lillian Bridwell-Bowles: Good evening, and welcome to the Annual Colloquium sponsored by the Center for Interdisciplinary Studies of Writing. My name is Lillian Bridwell-Bowles, director of the Center. The mission of our Center is to improve writing at the University of Minnesota and to sponsor scholarly activities that promote a rich climate for academic literacy. We’re in for some richness tonight. For those of you who saw this title in some alternative medium and thought glass/ware might be an episode of the Antiques Road Show, I want to tell you that you’re in the wrong place, but please stay and you won’t be disappointed. Tonight we present two inspiring talents: Ira Glass, host of This American Life; and Chris Ware, New Yorker comic artist and illustrator/author of Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth. They’ll engage each other in a conversation about their work and the successes they’ve had in contributing to new forms of public discourse. As we were planning this event, we were struck by comments both have made about the inadequacies of ordinary language, familiar forms of journalism, and traditional art forms to promote reforms of various sorts in America. Both have found unique combinations of the written and spoken word, sound and image to tell their powerful stories about American life—from efforts at school reform to religion to politics, to very private matters about identity.

Immediately after the interview tonight, we’ll invite questions from you. You should have received an index card as you entered the auditorium. Write your questions on these index cards and turn them in to the ushers as they circulate after the interview. When we finish with questions and answers, we invite you to join us for a reception in the lobby.

Ira Glass: Don’t they look different than what we thought?

Chris Ware: Oh, yes. Oh, boy.

IG: We were told that the organization that brought us here, its mission is to improve undergraduate writing at the University of Minnesota so if there are any students from other schools, please don’t follow any of our advice. So Chris, um …

CW: We’re going to start now? All right …

IG: Do you want to talk about how you ended up as a cartoonist? Was it something that you wanted to do as a kid, reading cartoons?

CW: I guess I should explain there’s this sort of neurosis that I have. I’ve only talked in front of a group of people a few times, and I actually didn’t graduate from the Art Institute of Chicago with my MFA because I had to give an oral report. Thus, I never got the credits to graduate. For somebody who sits at home at a table all day long, doing this is sort of torturous. But fortunately I can only see the first couple of rows here. I’m going to apologize in advance for everything that I may say and for the fact that I’m not a terribly articulate person, but anyway …

IG: Sometimes when I’ve been trying to explain to people who haven’t met you, Chris, what it’s like, what you’re like, I say, “Well, you know the clerk in High Fidelity? The really shy one?” I’d say, “Sort of like that, but more so.” Then I found out that you met Jack Black.

CW: Right, but you’re not talking about him though, right?

IG: You stood next to him, so it was like this scene in my head actually happening live in person.

CW: Yeah. Okay.

IG: One of the things that we were curious about is how many people here would actually know Chris’s work?

CW: Wow. That’s a surprise. That’s good.

IG: You might want to pull the mic a little closer.

CW: Oh, sorry. All right. That’s about five minutes now. Okay, so you had a question that I avoided already. What was it?

IG: Did you want to do cartoons when you were a kid?

CW: As a kid I read a lot of superhero comics. Or not actually read them, mostly I just looked at the pictures of the muscle-y men and tried to copy them, figuring to prepare myself to turn into that. It didn’t really happen. Most of the comics that I read as a kid were like Peanuts. My grandfather was a managing editor of a newspaper in Omaha, so he got a lot of free syndicated comic strip collections. I remember reading Peanuts a lot because there were characters I actually cared about, that seemed like genuine friends, or something like that, for a kid that wasn’t necessarily well-versed in terms of basketball and gym class. I guess I did grow up wanting to draw comics—for what reason, I’m not exactly sure.

IG: Did you think you would do it as a job, or were you just drawing comics?

CW: I didn’t think I’d ever do it as a job. There wasn’t any plan involved. I actually went to college thinking I would do comics. God knows why.

IG: You went to the Art Institute of Chicago for grad school.

CW: Right.

IG: Were they very supportive of the idea of somebody doing comic art?

CW: Not really. It was not a very supportive environment in general. There were a couple of teachers that were very good: Richard Keane, Bob Loescher. How many people in the audience are in art school here? A smattering of victims.

At the end of every semester in graduate school, you have to go through this thing called a critique, where a passel of instructors get together and just say whatever they feel like about what you’ve been doing all semester. You try to pour your heart into something or do something genuine and human, and they’ll just sit there. I’ve had teachers fall asleep when you’re trying to explain your artwork. One instructor actually accused me of drawing comics as a gig. He said, “So you do this gig, and then you come here and try to make art—I don’t get it.” Another teacher in that same critique session looked at the strip that I was working on, which was in color separation form. Basically every layer of printed ink color drawn on a separate acetate layer. He picked it up and held it as if it were some sculptural object and said, “Well, this is kind of nice.” He was looking at it upside down. Trying to get the art teachers to actually read the strips was the hardest part, because they weren’t used to reading something. They just wanted to look at it.

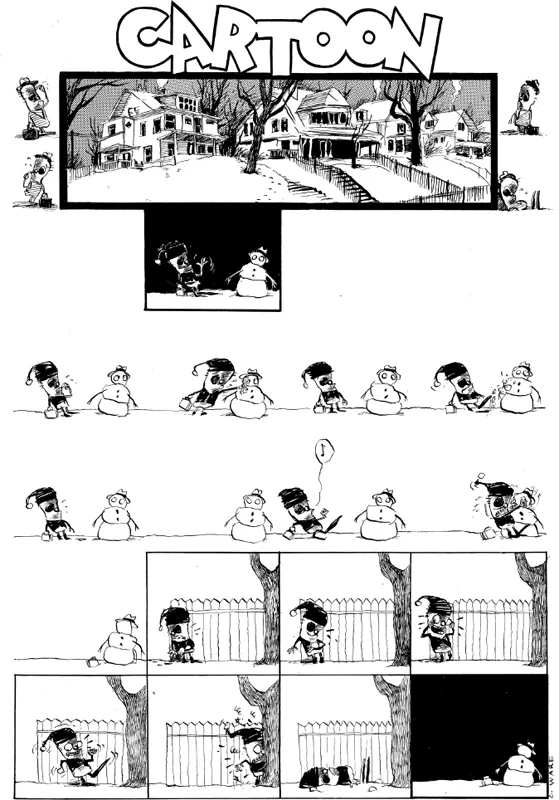

Potato Man strip published in The Daily Texan, 1988.

IG: When you were an undergrad at the University of Texas at Austin, you started drawing a strip called Potato Man, and you told the Comics Journal that it was the first time that you started to really enjoy what you were doing. You said that it was the first time in your adult life where you reclaimed the feeling you had as a kid: “I didn’t care why I was drawing what I was drawing. I was simply doing it.” What were you doing before then, and then what made that transition happen?

CW: I have slides of some very early embarrassing stuff I could show. Maybe I should just show the slides. Would that be the most sensible thing to do?

IG: Let’s do the slides.

CW: Again, I’m going to warn you, and I apologize in advance. A lot of these are slides of very early student work. It’s not good. On top of that, the slides are not good, so the two together do not make a pleasurable audio/visual experience. I will go through them as quickly as possible.

IG: Before you start them, could you just talk about that transition that happened with Potato Man? What happened?

CW: A girl broke up with me. That’s the truth. There was a sense of desperation, at that point, where I felt like nothing mattered anymore, and it seemed silly to try to invest art with such power, especially the art I was doing in school. It just seemed like there was too much weight being put on art as being dangerous, or something, and I just wanted the art basically to be my friend. That sounds pathetic, but it’s true.

IG: You mean there’s all this pressure from teachers, when you make art; it has to be Art with a capital A?

CW: Yes. Before I went to art school, I didn’t realize you had to try to defend your art, or you had to talk about it. Today I went and visited a class at the university here and they were having a critique. The very first critique I had took me by surprise. I go into class, everything’s hanging up on the wall, all of a sudden everybody’s staring at you, and you’re in a row and you have to talk about yourself. I couldn’t do it. It seemed weird. It never occurred to me that you have to do that. Of course, that’s art school, right there; that’s every week, basically.

IG: You were going into art more to avoid people.

CW: If you have to explain art, I think that it’s not really very successful art. [audience applause] That’s all the art students in here, I guess. Here I am onstage, so what am I doing here?

IG: Let’s see some of the slides.

CW: Okay, if you guys want me to stop just yell at me or something.

IG: Jason, let’s turn down the lights a bit on stage, so we can show these.

CW: Oh. Great. Okay. Like I said, I grew up reading comic books and wanted to draw superheroes. Most of the time I really wanted to watch them on television because it seemed much more real. I just copied the pictures out of the comics, like I might trace them. The only thing I knew about art was that it was something that people didn’t really do anymore. I figured that all people did now was advertising art or whatever. I knew about Renaissance drawing and that sort of thing, so when I went to art school I started trying to draw like that. This is from my freshman year. Then I had teachers tell me, “That’s an academic drawing; you need to change it.” They showed me people like Egon Schiele, Gustav Klimt, and this is the Schiele-Klimt rip-off.

IG: This is basically the same figure, but skinnier.

CW: Yes. Right. This was a few weeks later, basically. They said, “Well, you’re still too tight; you need to get messy and expressive.” So I thought, “Well, okay.” So, I got messy and expressive.

IG: This is the same figure but just sort of blurry now.

CW: Yes, they were all … naked, basically. At the same time I was doing a wretched comic strip for the student weekly, which I’m not going to name [Floyd Farland]. I don’t even want to show it anymore. But it was very derivative, sort of nonsense and very plot driven and silly, and that’s one page of it sort of set in the future. God, it’s embarrassing. This is a little bit later, a terrible art school painting. They were showing us all these new painters of the day, like David Salle and Robert Longo and people like that. I was trying to get at some sort of emotion by superimposing figures, and that kind of stuff. Of course I always kind of put comics into it, too.

IG: This picture is sort of a David Salle, a close-up of a face, and then two comic book figures in the front.

CW: Yes, I don’t know what I w...