![]()

Chapter 1

The Accidental Cartoonist

Larson’s Life and Career

Larson’s Upbringing and Family Life

We often expect our great comedians to come from dysfunctional roots (broken families, scenes of childhood trauma, economic hardship) that force the artist in later life to wield humor as a highly public coping mechanism. Larson gave a jokey nod, in fact, to that comedy truism in a 1989 book anthology; in the opening pages he showcased a series of pretend drawings from his childhood that illustrated demented beginnings: peeking out from behind bars on his bedroom window; sitting under the table at family dinner time with a rabid dog; tied to a tree by an oversized, torch-wielding brother; and being coaxed by his parents to run into the street to pursue some dangerously positioned chocolate chip cookies (Larson, “Fossil Record” 14–24). The reality of Larson’s early home life was more benign, of course, disappointing our expectations of creativity-producing dysfunction. He grew up, for example, in the suburbs of University Place, Tacoma, Washington, a fairly bland-sounding locale, with his parents, Vern and Doris—a car salesman and a secretary—who were, by all accounts, loving and highly supportive of their two sons’ interests. Moreover, Larson admired his older brother, Dan, with whom he was close friends throughout childhood and into adult life.

A minimal amount of probing just past this pleasant exterior reveals, nevertheless, a number of weird and unconventional (if not fully traumatic) aspects to Larson’s early family life: traditions, dynamics, and incidents that might explain why he ended up creating something as consistently morbid as The Far Side, instead of a comfortingly cute cartoon like “Ziggy or something” (Larson’s words) (Larson, “Commencement”). For starters, when Larson was a small boy, his family had a perverse taste for strange pranks and dark humor—establishing a sort of “Theodore Cleaver Meets the Thing” dynamic in which Gary could be torn from a sense of calm normality into a panic of sheer terror at any given moment (Larson, “This Is My Brother’s Fault” 1). His older brother, Dan, for example—though not inclined to inflict literal torture on his younger sibling, was a formidable antagonist who consistently “scared the hell out of him” (Weise). Larson explained that Dan “had studied me. He knew what scared me”; he was “some master from the Shau Lin Temple of Scaring Younger Brothers” (Larson, “Eye and I,” 540). As an example, Dan would sometimes convince his younger brother to venture into the basement, and then proceed to lock the door on him and turn off the light; as Gary desperately tried to force open the door, his brother would chant, “It’s coming, Gary, do you hear it? It’s coming … hear it breathing?” (Larson, “On Monsters” 268; Sherr).

At other times Dan would capitalize on Gary’s acute fear of monsters under the bed by hiding in the bedroom closet for hours, “just waiting for the golden opportunity to scare his sibling sick,” and then slowly open the door, inch by inch, maximizing the sense of suspense and terror (Ferguson). Larson recalls one such incident leaving him with a scarring, “indelible memory.” As the door opened inch by inch, almost imperceptibly, he was not able to take his eyes off the “black, vertical abyss” that surely contained a patiently malicious creature. He then let out a primal scream as “a single eye staring back” at him came into view—followed in the next moment by a smiling older brother who slowly revealed himself in a “very surreal fashion” (Larson, “Commencement” 1). Imagining such moments of real terror for a sensitive and imaginative kid adds a layer of poignancy to our reading of the dozens of “monster under the bed” cartoons Larson created—or to random gags about familial cruelty, like the classic where the father has rigged a contraption that intimidates his son into good behavior by simulating the knocking of a monster’s fist on a closed basement door (1/6/87; 2–7).

Gary also had to be wary of parents who enjoyed subjecting their kids to unusually disturbing pranks. He remembers, for example, needing good peripheral vision, since they were inclined to slip “a small invertebrate into [his] glass of milk at the dinner table while [his] head was turned”; or they might simply jump out and surprise him at unpredictable moments. Looking back, he recalled that his parents were especially talented at this kind of playful, predator–prey comedy that provoked a sense of nervous laughter mingled with low levels of “fear and humiliation.” Perhaps exaggerating a bit, he claims that they continually used “research, observation, psychology, biology” in “the quest to amuse” themselves at another family member’s expense. Larson thus lived in a state of comedic anxiety as a young kid, always prepared to either scream or laugh as a parent or brother waited just “around any corner, in any room,” ready to pounce. The average person might head for the therapist’s couch to work through the cognitive dissonance of household dynamics equally tied to silliness and horror; Larson went a different route, chalking up these experiences as productive drills in a “Far Side boot camp.” He effectively translated the lessons of that psychological teasing to the craft of cartooning, learning in his morbid gags to “study your prey, approach carefully, savor the moment, and then strike” (Larson, “On Dorothy” 4).

The celebration of morbid and juvenile humor was another unconventional aspect of the Gary’s childhood. Larson described the lowbrow comedic tone of family conversations:

Imagine your own father sitting at the Algonquin Round Table, surrounded by that famous group of New York intellectuals. Would he most likely attempt to use his verbal alacrity and facile mind to impress and entertain everyone? Or would he find a quiet moment and simply lean over and ask Dorothy Parker to pull his finger? (Sorry, Dad, but I know the answer to this one.) In short, the Larson Round Table was not a place where sharp dialogue and witticisms abounded. (Larson, “On Dorothy” 4)

He hastened to add that his parents (especially his mom) could be very smart and witty at other times but conceded that their jokes tended to be earthy and physical rather than cerebral; they liked to get down on their kids’ level, relishing goofy wordplay, engaging in slapstick, playing with taboo subject matter, and making “offbeat” or “wacky” observations. And because the Larson household was so steeped in this kind of irreverent comedy (effectively normalizing it in Larson’s mind), he often struggled as an adult to understand why some readers found his sense of humor to be so offensive or inappropriate (Gumbel).

Perhaps as compensation for all of the slapstick pranking, Larson’s parents gave him an unusual amount of freedom to explore the natural world when he was young. In stark contrast to how today’s parents helicopter over their kids in fenced-in backyards and groomed parks, Larson’s parents allowed him and his brother “on any given day or night” to gather up their “boots, nets and collecting jars and head for the local swamps or tidelands … on a quest for living treasure: the wetland fauna of western Washington” (Larson, “Syndrome” 180). Summertime expanded that range of freedom as he and Dan stayed for days and weeks at his grandparents’ farm on Fox Island in Puget Sound just off the Tacoma shore. Larson describes it as a “wondrous place” to explore—an island setting that “had a sort of “Lost World” feel to it.” Taking off from his grandparents’ house—which was set “in picturesque fashion … between the shore and a high bank … overgrown with trees and leafy vegetation,” they would venture into untamed fields, [and] tidelands.” Gary vividly remembers, in particular, a small creek that fed into a “a textbook swamp” featuring “crystal clear water,” a sandy bottom, and “salamanders everywhere” (Larson, “Big Ungulates” 446; Weise).

It was these forays into the natural world that first inspired Larson to think about becoming a scientist—and ultimately planted the roots of some of the key themes of The Far Side: wildlife conservation, intersections between animal and human realms, evolution, and a naturalistic worldview. Larson thus had the sensibility of a zoologist from an early age; in his words, he was continually “drawn to look under rocks, down holes, up trees, under water … to capture and to hold, if only for a few moments, some living, natural wonder, to observe it, examine it, have it touch your skin, feel its heartbeat against your hand—to ‘drink it in’ before it once again slips back over that invisible wall that separates Us from Them” (Larson, “Syndrome” 180–181).

In addition to observing animals, Larson collected them. He and his brother were continually bringing home bugs, lizards, and salamanders, filling bedrooms and the family basement with terrariums. His parents even allowed him to own a pet monkey for a time, and as he grew older, he developed a fondness for snakes, eventually taking care of close to twenty serpents (Kelly 86). The exotic nature of these pets sometimes got him into awkward situations that sound vaguely like premises for some of his classic cartoons. For example, his dad once discovered an eight-foot boa constrictor wrapped around his wife’s sewing machine; and when Larson was a young adult, he was forced to give away a fourteen-foot python when it tried to eat him instead of a dead rabbit during a feeding session (Kelly 86; Astor, “Larson Explores” 32). He admitted later in life that as a young boy he had been unaware that most people considered these animals—especially in those numbers—atypical or inappropriate pets: “Obviously, my social life was a bit down at the time …” and “it took me a while to realize that with an interest like that people are going to think there’s something wrong with you” (Gumbel). Imagining Larson’s conflicted emotions as he tried to reconcile his peculiar hobbies with conventional social expectations, you can see budding inspiration for the recurring theme of absurdly improper pets in The Far Side: a morose-looking giant squid cradling the family dog in the corner of a spare living room (4/14/86; 1–566); the alligator with an oblivious chicken perched on its snout, about to perform a violent party trick for guests in a suburban living room (3/8/86; 1–557); and the woman on the phone with her husband, patting her giant rhino on the head while holding the phone up to his snout, coaxing him, “C’mon baby … one grunt for Daddy … one grunt for Daddy (8/6/84; 1–410).

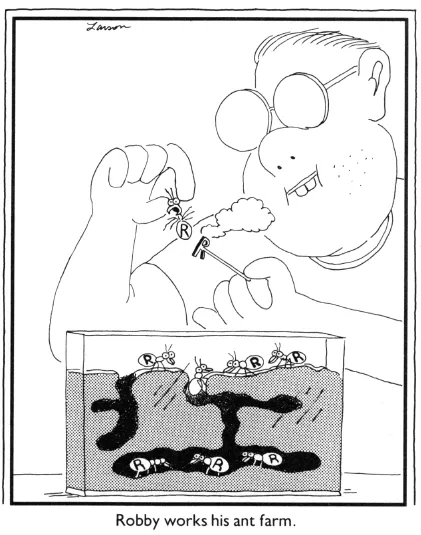

Fig. 1.1: Gary Larson, “Robby works his ant farm,” The Far Side, Nov. 7, 1986 (1-628).

Themes of scientific experimentation in The Far Side can also be traced to these childhood exploits. Gary and Dan, for example, once commandeered an entire room of their parents’ home to create a realistic desert ecosystem in which they could observe the natural behavior of their collected specimens. As you might guess, those informal studies would sometimes bleed into morbid territory, like when Gary became intrigued by the prospect of placing “two organisms … in a common jar” to see which one “would devour the other” (Barry D5). Based on these mildly gruesome vignettes, it is clear that Larson often embodied in spirit—if not in appearance—the chubby, bespectacled nerd in his cartoon who was continually doing half-scientific, half-horrific things with ant farms and other captured critters (fig. 1.1). Gothic themes also melded with science in Gary’s memories of how he helped his dad work on odd, experimental projects in a home workshop. He remembers himself as the bumbling but eager assistant—the “Igor” to his dad’s mad scientist. He would continually fetch the wrong tools, but his dad did not notice, or did not care, as he attempted, single-mindedly, “to bring life to a dead lawnmower” on a “stormy, lightning-filled” night (McCarthy).

The overlap of science and the supernatural was also a common theme throughout Larson’s childhood. When not out exploring the natural environment, he was immersed in entertainment that was populated with exotic animals, monsters, or aliens. These interests had fairly tame beginnings, as he first enjoyed sweetly conventional stories about anthropomorphized animals: tales of Br’er Rabbit or Mr. Toad read to him by his mother. His animal-themed affinities took a fairly morbid and naturalistic turn, however, when he fell in love with one particular book—Mr. Bear Squash-You-All-Flat—and asked his mom to read it to him repeatedly. He recalled, “There was something so mesmerizing about the image of this big bear going through the forest and squashing the homes of these little forest animals. I thought that was the coolest thing in the world” (Sherr). That dark sensibility was fed and amplified in subsequent years when his regular babysitter, Mrs. Wetch, introduced him to more vividly supernatural fare: Dracula, Frankenstein, werewolves, the Mummy, and the Creature from the Black Lagoon (Larson, “Good Wetch” 122). Larson’s taste in comics also fell within that borderland between the natural and fantastical. He liked stories of men mingling with apes—Alley Oop and Tarzan, in particular—and he would fixate on the details in these stories that appealed to his budding naturalist’s mind, like Edgar Rice Burroughs’ concocted dictionary of great-ape vocabulary. He memorized that entire glossary, in fact, and expanded his omnivorous reading habits to include other texts that satisfied his general interest “in wild animals, Africa and Nature” (Larson, “Jungle in My Room” 4).

Art was an additional creative outlet for Larson during these years, but he is quick to clarify that it should be “immediately obvious” that he never studied art formally while growing up—other than the random required class in grade school or junior high. On his own time he “loved to draw,” filling notebooks with doodles plumbed from his imagination and the natural world (Barry D5). While his classmates were sketching “cool tanks and airplanes,” he “preferred to draw dinosaurs, whales and giraffes” (McCarthy). This affinity for doodling persisted into high school, but during all those formative years he never once thought about (or was prodded toward) becoming a professional cartoonist. He explains that, “on Career Day in high school, you don’t walk around looking for the cartoon guy” (Larson, “Tribute to Stephen Jay Gould” 57).

Larson’s Teen and Young Adult Years

Later in life Larson shared scant information about his high school years. One can infer, nevertheless, that he was a bit of a social misfit who was more fixated on snakes and various nerdy occupations than stereotypical high school pursuits. In an honorary commencement address at his alma mater (Western Washington State University) in 1990, he explained that he was especially shy as a teenager but admired the unselfconscious kids who had the gumption to enter talent shows in high school: “I was really fascinated” by “the ones that got up there and made absolute fools out of themselves. It was like the equivalent of standing up in front of the entire student body and saying look at me everyone, I’m a nerd” (Larson, “Commencement”). Those impressions, in fact, seemed to inspire him eventually to pursue his own peculiar talents and passions; looking back, he said, “I realize though that those kids were pretty cool in a way because they were risk takers … they did something a little weird and it seems to me that we’re all sort of in a talent show of sorts. I mean there’s some point in our life that somewhere, sometime you’re gonna have to stand up in front of some stranger and do your act” (Larson, “Commencement”).

The outlines of Larson’s future performance were still vague when he attended college at Western Washington State University from 1972 to 1976. On a social level he thrived among other “weird” students in a dorm that had the reputation for carrying the lowest grade point average in the entire college. Sounding like a secondary character in the movie Animal House, he participated in a number of zany extracurricular activities: enrolling in a karate class on a whim and breaking a finger; spontaneously taking a road trip to Spokane and coming back with a pet boa constrictor; lurking for a semester in a creepy attic with a friend, feeling like a pair of “mutated rats”; cruising a sled across the college’s golf course after a freak snowstorm and landing in the hospital with a broken back; and—like a scene out of one of his more absurd cartoons—getting chased by an angry cow across a campus parking lot (Larson, Commencement).

Larson’s efforts as a student were equally eclectic, though slightly less odd. Initially he majored in science, but after attending his first slate of classes, he had a crisis of confidence; he decided against becoming a scientist after encountering a latent “fear of physics” and wrestling with worries about low job prospects for a biology graduate (Bernstein 104; Ferguson). While still seeking out every natural history and science class he could fit into his schedule, he began to roam more broadly in his course-taking, venturing into random territory like the history of opera. He ultimately settled on a fairly pragmatic and bland choice of major: communications. Perhaps trying to add some exciting purpose and justification to that decision, he remembers imagining that he would someday “save the world from mundane advertising” (Kelly 86).

The prospect of a career in the corporate world, however, also gradually dissipated, amounting to another phantom act. Instead, he essentially “bounced around” for a number of years after college, careening from job to job without a clear sense of his talents or what he wanted to do with his life. Music was his most avid interest during those years, but the job prospects in that field were fairly limited, of course. He labored for a time in a retail music shop and founded a trombone-and-banjo-based band “named ‘Tom and Larson,’ which friends immediately dubbed ‘two guys as exciting as their names’” (Weise). He also became enamored with the jazz guitar, seeking out any opportunity to study and play. This became a full-fledged passion, in fact, as he continued to pursue the craft throughout his adult life, later even devoting sabbaticals to studying with famous performers, and continually retreating into the wor...