- 311 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Future of Pakistan

About this book

With each passing day, Pakistan becomes an even more crucial player in world affairs. Home of the world's second-largest Muslim population, epicenter of the global jihad, location of perhaps the planet's most dangerous borderlands, and armed with nuclear weapons, this South Asian nation will go a long way toward determining what the world looks like ten years from now. The Future of Pakistan presents and evaluates several scenarios for how the country will develop, evolve, and act in the near future, as well as the geopolitical implications of each.

Led by renowned South Asia expert Stephen P. Cohen, a team of authoritative contributors looks at several pieces of the Pakistan puzzle. The book begins with Cohen's broad yet detailed overview of Pakistan, placing it within the context of current-day geopolitics and international economics. Cohen's piece is then followed by a number of shorter, more tightly focused essays addressing more specific issues of concern.

Cohen's fellow contributors hail from America, Europe, India, and Pakistan itself, giving the book a uniquely international and comparative perspective. They address critical factors such as the role and impact of radical groups and militants, developments in specific key regions such as Punjab and the rugged frontier with Afghanistan, and the influence of—and interactions with—India, Pakistan's archrival since birth. The book also breaks down relations with other international powers such as China and the United States. The all-important military and internal security apparatus come under scrutiny, as do rapidly morphing social and gender issues. Political and party developments are examined along with the often amorphous division of power between Islamabad and the nation's regions and local powers.

Uncertainty about Pakistan's trajectory persists. The Future of Pakistan helps us understand the current circumstances, the relevant actors and their motivation, the critical issues at hand, the different outcomes they might produce, and what it all means for Pakistanis, Indians, the United States, and the entire world.

Praise for the work of Stephen P. Cohen

The Idea of Pakistan: ""The intellectual power and rare insight with which Cohen breaks through the complexity of the subject rivals that of classics that have explained other societies posting a comparable challenge to understanding.""— Middle East Journal

India: Emerging Power: ""In light of the events of September 11, 2001, Cohen's perceptive, insightful, and balanced account of emergent India will be essential reading for U.S. foreign policymakers, scholars, and informed citizens.""— Choice

Led by renowned South Asia expert Stephen P. Cohen, a team of authoritative contributors looks at several pieces of the Pakistan puzzle. The book begins with Cohen's broad yet detailed overview of Pakistan, placing it within the context of current-day geopolitics and international economics. Cohen's piece is then followed by a number of shorter, more tightly focused essays addressing more specific issues of concern.

Cohen's fellow contributors hail from America, Europe, India, and Pakistan itself, giving the book a uniquely international and comparative perspective. They address critical factors such as the role and impact of radical groups and militants, developments in specific key regions such as Punjab and the rugged frontier with Afghanistan, and the influence of—and interactions with—India, Pakistan's archrival since birth. The book also breaks down relations with other international powers such as China and the United States. The all-important military and internal security apparatus come under scrutiny, as do rapidly morphing social and gender issues. Political and party developments are examined along with the often amorphous division of power between Islamabad and the nation's regions and local powers.

Uncertainty about Pakistan's trajectory persists. The Future of Pakistan helps us understand the current circumstances, the relevant actors and their motivation, the critical issues at hand, the different outcomes they might produce, and what it all means for Pakistanis, Indians, the United States, and the entire world.

Praise for the work of Stephen P. Cohen

The Idea of Pakistan: ""The intellectual power and rare insight with which Cohen breaks through the complexity of the subject rivals that of classics that have explained other societies posting a comparable challenge to understanding.""— Middle East Journal

India: Emerging Power: ""In light of the events of September 11, 2001, Cohen's perceptive, insightful, and balanced account of emergent India will be essential reading for U.S. foreign policymakers, scholars, and informed citizens.""— Choice

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Future of Pakistan by Stephen P. Cohen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & American Government. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

American Government1 | STEPHEN P. COHEN Pakistan: Arrival and Departure |

How did Pakistan arrive at its present juncture? Pakistan was originally intended by its great leader, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, to transform the lives of British Indian Muslims by providing them a homeland sheltered from Hindu oppression. It did so for some, although they amounted to less than half of the Indian subcontinent's total number of Muslims. The north Indian Muslim middle class that spearheaded the Pakistan movement found itself united with many Muslims who had been less than enthusiastic about forming Pakistan, and some were hostile to the idea of an explicitly Islamic state.

Pakistan was created on August 14, 1947, but in a decade self-styled field marshal Ayub Khan had replaced its shaky democratic political order with military-guided democracy, a market-oriented economy, and little effective investment in welfare or education. The Ayub experiment faltered, in part because of an unsuccessful war with India in 1965, and Ayub was replaced by another general, Yahya Khan, who could not manage the growing chaos. East Pakistan went into revolt, and with India's assistance, the old Pakistan was broken up with the creation of Bangladesh in 1971.

The second attempt to transform Pakistan was short-lived. It was led by the charismatic Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who simultaneously tried to gain control over the military, diversify Pakistan's foreign and security policy, build a nuclear weapon, and introduce an economic order based on both Islam and socialism. He failed even more spectacularly than Ayub Khan and Yahya Khan. Bhutto was hanged in a rigged trial organized by General Mohammed Zia ul-Haq, who took Islam more seriously. With U.S. patrons looking the other way and with China and Saudi Arabia providing active support, Zia sought a third transformation, pursuing Islamization and nuclear weaponization. He further damaged several of Pakistan's most important civilian institutions, notably the courts (already craven under Ayub), the universities, and the civil service.1 Zia was very shrewd—and he was also a fanatic with strong foreign backing because his support for the Afghan mujahideen helped bring down the Soviet Union.

After Zia's death, from 1989 to 1999, Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif alternated in office during a decade of imperfect democracy, groping toward the recreation of Jinnah's moderate, tolerant vision of Pakistan. In fact, the 1990s, which often are referred to as the “lost decade” in terms of economic growth, witnessed a high rise in urban and rural poverty levels. The growth rate in the 1980s averaged 6.5 percent, but in the 1990s real GDP growth declined to 4.6 percent.

Benazir and Nawaz were unable to govern without interference from the military and the intelligence services, which under Zia had vastly expanded their domestic political role. The army believed that it was the keeper of Pakistan's soul and that it understood better than the politicians the dangers from India and how to woo outside supporters, notably the Americans, the Saudis, and the Chinese. The 1990s—the decade of democracy—saw Benazir and Nawaz holding a combined four terms as prime minister. In this period the press was freed from government censorship (Benazir's accomplishment) and there was movement to liberalize the economy (Sharif's contribution), although neither clamped down on growing Islamist movements nor did much to repair the state apparatus, which had been badly weakened over the previous thirty years. Nor were either of them able to reclaim civilian ground from the military, which by then had developed a complicated apparatus for fixing Pakistan's elections. Benazir invested in education, but the state was unable to implement her policies, and Nawaz turned to the military to exhume the “ghost schools” that Benazir claimed she had built. There were also ghost computers: one of the projects that she liked to boast about involved the wide distribution of computers to schools and villages, which had never happened.

Musharraf: Another Failed General

When General Pervez Musharraf seized power in a bloodless coup on October 12, 1999, he undertook Pakistan's fourth transformation. Musharraf came to power after he launched a politically and militarily catastrophic attack on India in the Kargil region of Kashmir and then blamed Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif for its failure. He believed that the politicians had had their opportunity. Ten years of imperfect democracy had not turned Pakistan's economy around or addressed the country's many social and political tensions, and Musharraf, fresh from his coup, told me that “this time he would ‘fix' the johnnies [corrupt and incompetent politicians and bureaucrats],” setting Pakistan on the right course under the army's tutelage. He rejected my suggestion that corrupt or guilty politicians be removed and that fresh elections be held to bring a new generation of competent politicians to power, the argument being that it takes time to build a democracy and that politicians should be allowed to make mistakes and learn from them. Musharraf would have none of that, as he was confident that with the backing of the military he could launch still another reformation of the Pakistani state and nation. The highlights of Musharraf's domestic reform strategy included

—Fiscal and administrative devolution to the districts, which further weakened the powers of Pakistan's provincial governments; the system was later abandoned.

—Privatization of state-owned assets, which resulted in a huge inflow of money into the treasury.

—Promotion of a poverty-reduction strategy.

—Creation of the National Accountability Bureau, which was extremely controversial; and at one point the bureau was shut down.

—Breaking the monopoly of state-owned media and promoting a free press, although toward the end of his period in office Musharraf declared a state of emergency.

—Empowerment of the Higher Education Commission and establishment of new universities.

—Reservation of seats in Parliament for women.

—Signing of the Women's Protection Bill in an attempt to reform the rigid Islamist-inspired Hudood laws.

—Enacting anti-terrorism measures, which, although they represented a strong public stance against sectarian violence, were in practice ineffective.

—Registration of madrassas and development of new curriculums, which also was unsuccessful.

Musharraf turned to the technocrats for guidance, transforming the system of local government and selling off many state assets (thus improving the balance of payments problem, which always is severe for a country with little foreign investment and hardly any manufacturing capability). He further opened up the airwaves and in 2000 attempted to tame the judiciary, making them take a fresh oath of office swearing allegiance to him. One of Musharraf's cherished goals, often repeated publicly and privately, was to tackle “sectarian violence,” the code for Sunni-Shiite death squads and organized mayhem, but it actually intensified. Finally, while having signed up for the G. W. Bush administration's “global war on terror,” his government never actually stopped supporting militant and violent groups in Afghanistan, Kashmir, and India itself.

Musharraf did introduce some important changes in relations with India. These were on his mind when he first came to power, and after several years he began to float proposals on Kashmir and a secret back-channel dialogue was established. It was clear from my conversations with other generals at that time that they regarded that approach as naive but were willing to go along with Musharraf to see whether there were any positive results.2

Musharraf had an idealized vision of what he wanted Pakistan to become, but he was no strategist. He neither ordered his priorities nor mustered the human and material resources to systematically tackle them one after another. He behaved as president just the way he behaved as a general: he was good at public relations but bad at details and implementation. His greatest accomplishment came when he left things alone—for example, by allowing electronic media to proliferate to the point that Pakistan now has more than eighty television channels, although many of them lack professional standards. On the other hand, his greatest failure—and a calamity for Pakistan—may have been his permissive or lax attitude toward Benazir Bhutto's security. A report issued by the United Nations holds him responsible in part for her murder,3 which removed the most talented of all Pakistani politicians, despite her flaws, and further undercut Pakistan's prospects.

Musharraf began to lose his grip on power because of his seeming support of an unpopular war in Afghanistan and his strategic miscalculation of Pakistani public opinion, which led him to believe that a public protest movement against his high-handed tactics by judges and lawyers would dissipate. He, like his military predecessors, had to turn to civilian politicians for moral authority after about three years of rule, but doing so failed to generate legitimacy for Musharraf, just as it had failed Ayub and Zia.

In March 2007, Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry was summoned by Musharraf and asked to resign. When he refused to do so, Musharraf suspended him (a first in Pakistan's history), initiating a chain of events that eventually led to Musharraf's own downfall. Chaudhry was subsequently reinstated by the Supreme Court in July, which would soon after deliberate Musharraf's eligibility as a legitimate candidate in the elections. Musharraf declared a state of emergency in November 2007, suspending both the country's constitution and the supreme court judges. Because his decisions were fiercely opposed by the community of lawyers, civil society organizations (both liberal and Islamist), and a very vocal population, Musharraf was almost entirely isolated. In 2008, there was civil unrest, rioting, antigovernment protests, and mass support for the lawyers' movement. One leader emerged from this spectacular display of people's power: Aitzaz Ahsan, a Pakistan People's Party (PPP) member and distinguished lawyer. Ahsan, who was not part of the PPP's inner circle or close to President Asif Ali Zardari, has since kept a low profile.4 Pro-Islamist sentiments were part of the lawyers' movement, which expanded its popular appeal, riding a wave of anti-Americanism.

There were more frequent attacks on U.S. and Western targets by militant Islamists, who made several attempts to kill Musharraf himself. Besides the 9/11 attacks in New York and Washington, there was another momentous development, this one in Pakistan itself: the razing of the Lal Masjid (Red Mosque). The mosque was located in the heart of Islamabad, close to Islamabad's leading hotel, the diplomatic enclave, and the new headquarters of the Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate (ISI). The mosque had close ties to militant groups, some of them patronized by the ISI. The government's attack on the mosque came not at the behest of Washington but of Beijing, regarded by elite Pakistanis as their most reliable supporter. China, like the West and India, was deeply concerned about the growth of Islamist militancy in Pakistan and the training of Chinese Muslims in militant camps. The Chinese ambassador complained publicly about the taking of female Chinese workers as hostages by a women's group associated with the Lal Masjid.

According to military sources, the army's operation killed 102 people, but independent media claim that there were 286 to 300 dead, including many women and young girls. Islamabad residents recalled the stench of rotting bodies.5 There were other terror attacks by militant Islamists, and Pakistani public opinion hardened against both the United States and Musharraf after Pakistani sovereignty was clearly violated by drone attacks against militants within Pakistan. The army's reputation suffered, and in 2007, officers were warned by Musharraf not to wear their uniforms outside cantonments.

Instances of organized violence, including suicide attacks, have shown no clear trend, but they were more lethal in 2010 than in 2009. There was a major decline in terrorist attacks from 2009 to 2010, with 687 incidents in Pakistan in 2010 (down from 1,915 in 2009) resulting in 1,051 fatalities (down from 2,670). As of December 2010 there had been fifty-two acts of suicide terrorism, down from eighty in 2009, but they were more lethal, with 1,224 deaths in 2010, up from 1,217 in 2009.6

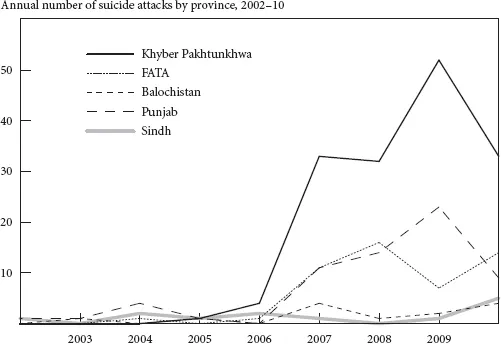

Figure 1-1 shows the annual number of suicide attacks in Pakistan from 2002 to 2009, by province. Despite the decline, the figures again ranked the country third in the world in both number of attacks and deaths, after Afghanistan and Iraq. Suicide bombing is a relatively new scourge in Pakistan. Only two suicide bombings were recorded there in 2002, but the number grew to fifty-nine in 2008 and to eighty-four in 2009, before dropping to twenty-nine in 2010, the lowest level since 2005. Still, in 2010 Pakistan was the site of far more deaths caused by suicide bombing (556) than any other country and accounted for about one-quarter of all such bombings in the world. The largest number of deaths and attacks took place in the Pashtun belt in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), with Pashtuns killing Pashtuns, whereas the so-called Punjabi Taliban (consisting of Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, Jaish-e-Muhammad, and others) targeted Shiites, Barelvis, and Ahmediyyas as well as Christians.7

Figure 1-1. Annual Number of Suicide Attacks in Pakistan, by Province, 2002-10a

Source: Brookings Institution Pakistan Index (www.brookings.edu/~/media/Files/Programs/FP/pakistan%20index/index.pdf).

a. In addition to the attacks noted above, two additional attacks occurred in Azad Kashmir during 2009, bringing the yearly total to eighty-seven.

One Indian observer notes that neither the intensified operations by the Pakistan army in the KP nor U.S. drone attacks have dented the motivation of the Pashtun, both Afghan and Pakistani, nor have they diminished the Punjabi Taliban.8

Zardari Treading Water

Benazir Bhutto's widower, Asif Ali Zardari, was elected president on September 6, 2009, with the support of the PPP and in coalition with other secular parties, until the coalition collapsed in January 2011. Politics in Pakistan seems to be reverting to its normal fluid state as parties come and go, leading to uncertain leadership in Sind and Balochistan, in particular. As of 2011 Punjab remains stable, under the leadership of Nawaz's brother, Shahbaz Sharif, but the army seems to be again grooming favored politicians (such as the mercurial former cricket player, Imran Khan) for leadership roles. Being forced to govern in a coalition has its problems, but it has taught Pakistani politicians the virtues of cooperation and some of the “rules of the game” of a democratic political order.

Little was expected of Zardari, a Karachi-born, Sindhi-speaking politician from Punjab's Multan district, but in partnership with stalwart PPP members, his government, led by Prime Minister Yusuf Reza Gilani, has performed better than any prior civilian government—not a great accomplishment, but one that should not be belittled.

The new government's agenda is largely that of Benazir Bhutto: reform and restoration rather than transformation. She had lofty goals, but at the end of her life she understood how badly Pakistan had been governed, even by herself, and she indicated to acquaintances that just as her second term as prime minister had been better than the first, in a third term as prime minister she would have more clarity and purpose. She had the charisma, the international contacts, and the experience of governance that might have given Pakistan half a chance at some kind of success, despite her flaws. That shows that those who killed her knew what they were about, and her death, especially the way that she died, was a tragedy for Pakistan that dramatically reduced the country's odds of emerging from its thirty-year crisis as a normal state.

Zardari lacked his wife's brilliance and charisma. There was a systematic attempt by the opposition and the intelligence services to portray him as corrupt, and his reputation for corruption was one of her greatest political liabilities. Zardari's defense to visitors is that he has never been convicted of any crime, but that, of course, is true of most Pakistani politicians whose reputation for corruption equals or surpasses his. Complaints about corruption have faded in 2011, as the problems facing Pakistan—notably terror attacks—have shifted attention to the military and its inability to control domestic violence.

In the three years of Zardari's presidency, there have been significant changes in Pakistan's constitutional arrangements and an attempt to rebuild some of the badly weakened institutions of the Pakistani state. “Civil society” is booming, the press tentatively exercises its new freedoms (in 2010 Pakistan earned the dubious honor of being the deadliest place in the world for journalists to practice their craft9), and growing concern about social inequality, education, and governance has given rise to all kinds of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), both modernizing and Islamist.

A wide gap remains between the government and the people of Pakistan. Except, paradoxically, for the Islamist Jamaat-e-Islami (JeI), internal party democracy is nonexistent. Distrust still permeates Pakistan's political order, and there remains a deep fear of the security services. The civilian government is still dependent on the military, especially as the internal security situation worsens. Pakistan's foreign friends are as unpredictable as ever.

Zardari's major accomplishments, many of which were the result of cooperation with Prime Minister Gilani, include restoration of the chief justice and deposed judges, unanimous approval by all four provinces of the Seventh National Finance Commission Award, passage of the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, and continuity of national economic policy.

Restoration of the Chief Justice and Deposed Judges. Chief Justice Iftikhar Ahmed Chaudhry and all judges previously deposed by Musharraf were reinstated on March 21, 2009, by Zardari, albeit under pressure from the army. There are indications that the new Supreme Court adheres more closely to international judicial standards than its predecessor.10

Agreement on the Seventh National Finance Commission (NFC) Award. The NFC award is the annual distribution by the federal government of financial resources among the provinces of Pakistan, the terms of which have been the cause of bitter disagreement. Under the Zardari government, the Seventh NFC Award was unanimously approved by all four provinces in December 2009 through a consultative process, leading to improved relations between the provinces and to fiscal decentralization. In a distinct depar...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1 - Pakistan: Arrival and Departure

- 2 - Pakistan's Future: Muddle along

- 3 - Radicalization, Political Violence, and Militancy

- 4 - Addressing Fundamental Challenges

- 5 - Looking Ahead

- 6 - The China Factor

- 7 - Factors Shaping the Future

- 8 - The Clash of Interests and Objectives

- 9 - Still an Uncertain Future

- 10 - Visualizing a Shared India-Pakistan Future

- 11 - At the Brink?

- 12 - Security, Soldiers, and the State

- 13 - Looking at the Crystal Ball

- 14 - Regime and System Change

- 15 - Population Growth, Urbanization, and Female Literacy

- 16 - The Perils of Prediction

- 17 - Youth and the Future

- 18 - Afterword

- Contributors

- Index

- Back Cover