eBook - ePub

To Serve the President

Continuity and Innovation in the White House Staff

- 450 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Nobody knows more about the duties, the difficulties, and the strategies of staffing and working in the White House than Brad Patterson. In To Serve the President, Patterson combines insider access, decades of Washington experience, and an inimitable style to open a window onto closely guarded Oval Office turf. The fascinating and entertaining result is the most complete look ever at the White House and the people that make it work.

Patterson describes what he considers to be the whole White House staff, a larger and more inclusive picture than the one painted by most analysts. In addition to nearly one hundred policy offices, he draws the curtain back from less visible components such as the Executive Residence staff, Air Force One and Marine One, the First Lady's staff, Camp David, and many others—135 separate offices in all, pulling together under often stressful and intense conditions.

This authoritative and readable account lays out the organizational structure of the full White House and fills it out the outline with details both large and small. Who are these people? What exactly do they do? And what role do they play in running the nation? Another exciting feature of To Serve the President is Patterson's revelation of the total size and total cost of the contemporary White House—information that simply is not available anywhere else.

This is not a kiss-and-tell tale or an incendiary exposé. Brad Patterson is an accomplished public administrator with an intimate knowledge of how the White House really works, and he brings to this book a refreshingly positive view of government and public service not currently in vogue. The U.S. government is not a monolith, or a machine, or a shadowy cabal; above all, it is people, human beings doing the best they can, under challenging conditions, to produce a better life for their fellow citizens. While there are bad apples in every bunch, the vast majority

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access To Serve the President by Bradley H. Patterson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & American Government. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

American GovernmentThe White House Overall | PART I |

Overall Organization of the White House

1 | The Contemporary White House Staff |

A president-elect can be expected to ask:

How did the White House staff get to be what it is?

How much of it is fixed in statute and how much of it can a new president reshape?

What are its organizational elements? How much continuity has there been?

What innovations have been made by recent presidents?

How many men and women typically work there?

How much does it cost to operate the whole White House?

In fact, President George W. Bush did ask:

How do you intend to get advice from people you surround yourself—who are you going to surround yourself [with]? And what process will you have in place to ensure that you get the unvarnished opinion of advisers? Because whoever sits in the Oval Office is going to find this is a complex world, with a lot of issues coming into the Oval Office—a lot—and a great expectation in the world that the United States take the lead. And so my question would be, how do you intend to set up your Oval Office so that people will come in and give you their advice?1

How Did the White House Staff Get to Be What It Is?

The environment out of which the modern White House staff was born, at the end of Franklin Roosevelt's first term, was, like any other difficult birth: messy and painful. At first, FDR tried to rely on his cabinet departments. “From July 1933 to September 1935,” reports presidential scholar Matthew Dickinson,

he experimented with at least five different cabinet-level coordinating councils. But, despite his repeated attempts to make their deliberations more effective, these coordinating councils proved unable to meet his bargaining needs. By the end of 1935 he was genuinely worried that his administrative shortcomings might jeopardize his reelection chances…. Not surprisingly, Roosevelt spent a large portion of his waking hours soothing ruffled feathers and resolving administrative disputes. The maintenance of peace in his official family took up hours and days of Roosevelt's time that could have been used on other matters…. The cumulative impact of FDR's organization strategy…was administrative disarray.2

This disarray reached such proportions that consultant Louis Brownlow, on a trip to Europe, encountered pessimism abroad as to whether democracies could govern effectively when beset with economic and national security calamities. He later recalled, “It was our belief that the Presidency of the United States was the institution…behind which democrats might rally to repel the enemy. And, to that end, it was not only desirable but absolutely necessary that the President be better equipped for his tremendous task.” 3

Roosevelt had been meeting with several experts in public administration, including Brownlow, Charles Merriam, and Luther Gulick, to discuss government planning at the national level, and he had read a December 1935 memorandum from Merriam recommending a study of how an executive staff “should be organized, what its functions should be, and its relations to the operating agencies.” 4 In February 1936, Roosevelt had an hour-long meeting with Merriam and others to discuss how such a study might be undertaken. FDR was satisfied that he had shaped the research agenda of the study to his satisfaction and was confident that he had enough personal influence on the thinking of the three leaders; on March 20,1936, he appointed Brownlow, Merriam, and Gulick as the President's Committee on Administrative Management. He instructed them not to share their deliberations with any of his three principal White House aides, and then let the committee alone, busying himself with his reelection.

After his electoral victory the president met with the committee (Merriam was absent) on November 14, 1936. When presented with their recommendation to enhance his personal staff by six administrative assistants, of whom one would function as a kind of de facto staff director over the others, FDR balked; staff direction would remain in his own hands. “He refused to delegate staff ‘coordination’ to any single subordinate,” Dickinson emphasized, adding “Roosevelt's administrative philosophy, as expressed in the Brownlow Committee Report, is clearly antithetical to subsequent staff development during the last half century.” 5

The following January 10, Roosevelt convened an extraordinary press conference at which he unveiled the Brownlow Committee's report with its proposals for “not more than six” administrative assistants and sent Congress draft legislation to give statutory authorization to this new White House staff. For two years Congress huffed and puffed but took no final action to meet the president's request.6 (This was the same period when FDR was pushing his failed plan to augment the membership of the Supreme Court.)

On April 3, 1939, however, Congress did enact the Reorganization Act of 1939, which began:

SECTION I. (a) The Congress hereby declares that by reason of continued national deficits beginning in 1931, it is desirable to reduce substantially Government expenditures and that such reductions may be accomplished in some measure by proceeding immediately under the provisions of this Act. The President shall investigate the organization of all agencies of the government and shall determine what changes therein are necessary to accomplish the following purposes:

…

(2) to increase the efficiency of the operations of the Government to the fullest extent practicable within the revenues;

…

(b) The Congress declares that the public interest demands the carrying out of the purposes specified in subsection (a) and that such purposes may be accomplished in great measure by proceeding immediately under the provisions of this title, and can be accomplished more speedily thereby than by the enactment of specific legislation.7

President Roosevelt took up that invitation to “proceed immediately.” On April 25, 1939, he submitted Reorganization Plan Number One, which included authorization for an institutional staff unit entitled “Executive Office of the President,” but it was silent about any White House office, that is, any personal staff for the president. Congress approved the plan; it became effective on July 1,1939.8

Taking these two congressional enactments together, Roosevelt saw his opportunity. On September 8,1939, he issued his own Executive Order 8248—in effect the birth certificate for the modern White House. It begins: “By virtue of the authority vested in me by the Constitution and Statutes, and in order to effectuate the purposes of the Reorganization Act of 1939…and of Reorganization Plan No I…it is hereby ordered as follows: There shall be within the Executive Office of the President the following principal divisions, namely (1) The White House Office….”

Part II, Section 1 of the order went on to specify that this new office was to be composed of “Secretaries to the President,” an executive clerk, and administrative assistants to the president. These last were:

To assist the President in such matters as he may direct, and at the specific request of the President, to get information and to condense and summarize it for his use. These Administrative Assistants shall be personal aides to the President and shall have no authority over anyone in any department or agency, including the Executive Office of the President, other than the personnel assigned to their immediate offices. In no event shall the Administrative Assistants be interposed between the President and the head of any department or agency or between the President and any one of the divisions in the Executive Office of the President.

The originating document of the modern White House staff was thus not a statute but an executive action, amendable by any subsequent president. It set up a White House staff “with no authority over anyone in any department or agency,” and it instructed White House staffers never to “interpose” themselves between the president and his cabinet. Echoes of these commands still reverberate in the White House sixty-nine years later.

The White House in Statute

Since its first appearance in the appropriations act for 1940, the term The White House Office appears often in statutes, but not in the sense of establishing any part of the White House staff or specifying the duties of any of its officers.

There are three exceptions to this statement. The first is the National Security Act of 1947, which created the National Security Council (NSC). The act specifies that the council “shall have a staff to be headed by a civilian executive secretary who shall be appointed by the President…[and who may] appoint…such personnel as may be necessary to perform such duties as may be prescribed by the council….” The second instance of congressional creation of presidential staff is in the Homeland Security Act of 2002, which establishes the Homeland Security Council (HSC) and in similar language creates an executive secretary for the HSC.9 Other than the president and the vice president, these are the only two positions in the entire White House that are creations of statute; to disestablish them congressional action would be required.

The third statute that prescribes any White House staff duties is the law requiring the Secret Service to protect the president, the president-elect, the vice president, and the vice president-elect, even if any of those four protectees would prefer to decline the protection.10

In 1978 a comprehensive statute was enacted “to clarify the authority of personnel in the White House and the Executive Residence at the White House [and] to clarify the authority for the employment of personnel by the President to meet unanticipated needs….” 11 The president is “authorized to appoint and fix the pay of employees in the White House Office without regard to any other provision of law regulating the employment or compensation of personnel in the Government service.” As to what the staff is to do, the statute simply says that White House employees “shall perform such official duties as the President may prescribe.” In addition, the president is authorized to expend “such sums as may be necessary” for the official expenses of the Executive Residence and the White House Office. Assistance is also authorized for the domestic policy staff, the vice president, the spouse of the president, and the spouse of the vice president. The same statute does impose limits on the numbers of civil service supergrades to be employed in the White House Office, but for positions at GS-16 and below permits “such number of other employees as he [the president] may determine to be appropriate.” The hiring of experts and consultants is also authorized. Finally, the 1978 statute authorizes any executive branch agency to detail employees to the White House providing that the detailing agencies are reimbursed for their detailees’ salaries after 180 days and that the White House annually reports the numbers of detailees to Congress for public disclosure. Significantly, the key verb throughout this statute is “authorize,” not “establish.”

A 1994 act requires the White House to send to the House and Senate Governmental Affairs Committees each July 1 a list of all White House employees and detailees by name, position, and salary (excluding only individuals the naming of whom “would not be in the interest of the national defense or foreign policy.”)12

Each year, of course, there is an appropriations statute that fixes the outlays permitted for salaries and expenses of the employees in the White House Office. In their 1998 act the Appropriations Committees inserted a provision requiring reimbursements when outside groups are invited to use the White House (chapter 2).

With the three noted exceptions, therefore, no statute of Congress by itself creates or abolishes any unit of the White House staff, prescribes organizational structure, or delineates the specific duties any staff member is to perform for the president. The new president can be assured that, legally, he or she has practically full flexibility to reshape the structure and organization of the White House staff and to fix the duties of every person serving there.

The Organizational Elements of the White House Staff

While the White House Office started with Franklin Roosevelt, the modern White House really took shape in the administration of Dwight D. Eisenhower. As World War II ended, the whole federal policymaking environment had shifted, creating new demands on White House leadership. The distinction between domestic and foreign affairs was evaporating. While cabinet agencies were still stovepiped into separate departments, the separateness of their areas of policy concern was disappearing. Diplomacy, the use of U.S. armed forces, intelligence, and the conduct of covert action were all integrated within the policy area of “national security”; economics, finance, trade, commerce, and agriculture were inseparable from one another, as were science, space, and the uses of nuclear power. New institutions appeared: the Department of Defense, the Central Intelligence Agency, the U.S. Information Agency, the National Security Council, the Operations Coordinating Board, the Marshall Plan, the Point Four foreign assistance program, the Agency for International Development.

Eisenhower shaped his White House staff to meet these new institutional demands. He:

—Enhanced the role of the vice president by inviting Nixon to attend cabinet and NSC meetings.

—Created the positions of chief of staff and deputy chief of staff at the White House.

—Created the post of assistant to the president for national security affairs and made its holder the supervisor of the NSC staff.

—Instituted the position of staff secretary at the White House.

—Created the first cabinet secretariat, and used the cabinet regularly for the discussion of domestic policy issues.

—Enlarged the White House congressional affairs office; its head was his deputy chief of staff.

—Created the White House post of special assistant for intergovernmental affairs to enhance direct relationships with state and local governments.

—Instituted the White House position of special assistant for science and technology (which later became the Office of Science and Technology Policy in the Executive Office).

—Brought live television into his press conferences.

—Instituted a system of written reports from cabinet secretaries directly to the president to signal him about policy decisions being made at lower levels or about brewing problems. (Called “Staff Notes,” this practice later became the system of weekly cabinet reports.)

—Began the use of helicopters, to and from Camp David, for instance; this facility is now managed by the Marine Corps as the HMX-One squadron (in the White House Military Office).

All of these staff enhancements instituted by Eisenhower have proved their worth to the presidency and have accordingly been continued—and expanded further—by succeeding presidents, creating a kind of baseline continuity in the staff structure of the White House.

But, reflecting their respective policy priorities, every president since Eisenhower has added innovations in the functions and staffing of the White House. President Kennedy gave his vice president a downtown office—at the White House—and, after the Bay of Pigs disaster, instituted a White House Situation Room; President Johnson added a curator to the staff; Gerald Ford began an intern program; President Carter enhanced the policy role of the vice president; ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

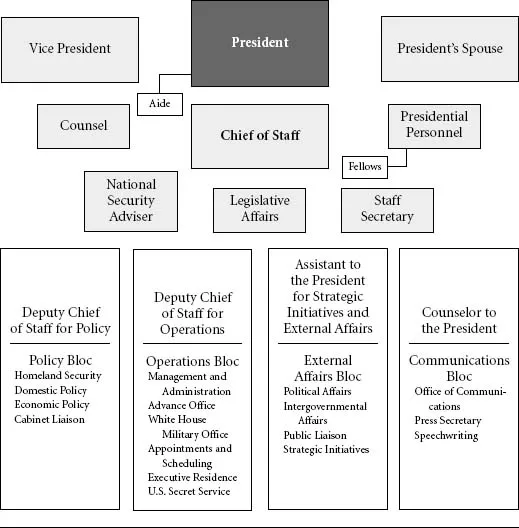

- Part One - The White House Overall

- Part Two - The Top Crosscutting Leadership

- Part Three - The Policy Bloc

- Part Four - The Strategic Initiatives and External Affairs Bloc

- Part Five - The Communications Bloc

- Part Six - Special Counselors to the President

- Part Seven - The Operations Bloc

- Part Eight - The Physical White House and its Environment

- Part Nine - Looking to the Future

- Appendix: Component Offices of the Contemporary White House Staff

- Notes

- Index

- Back Cover