eBook - ePub

Wiki Government

How Technology Can Make Government Better, Democracy Stronger, and Citizens More Powerful

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Wiki Government

How Technology Can Make Government Better, Democracy Stronger, and Citizens More Powerful

About this book

Collaborative democracy—government with the people—is a new vision of governance in the digital age. Wiki Government explains how to translate the vision into reality. Beth Simone Noveck draws on her experience in creating Peer-to-Patent, the federal government's first social networking initiative, to show how technology can connect the expertise of the many to the power of the few. In the process, she reveals what it takes to innovate in government.

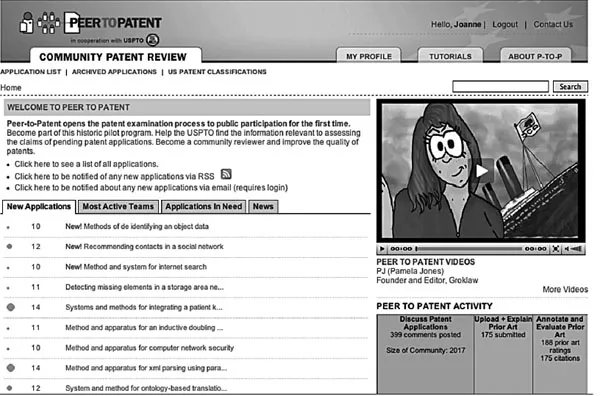

Launched in 2007, Peer-to-Patent connects patent examiners to volunteer scientists and technologists via the web. These dedicated but overtaxed officials decide which of the million-plus patent applications currently in the pipeline to approve. Their decisions help determine which start-up pioneers a new industry and which disappears without a trace. Patent examiners have traditionally worked in secret, cut off from essential information and racing against the clock to rule on lengthy, technical claims. Peer-to-Patent broke this mold by creating online networks of self-selecting citizen experts and channeling their knowledge and enthusiasm into forms that patent examiners can easily use.

Peer-to-Patent shows how policymakers can improve decisionmaking by harnessing networks to public institutions. By encouraging, coordinating, and structuring citizen participation, technology can make government both more open and more effective at solving today's complex social and economic problems. Wiki Government describes how this model can be applied in a wide variety of settings and offers a fundamental rethinking of effective governance and democratic legitimacy for the twenty-first century.

Launched in 2007, Peer-to-Patent connects patent examiners to volunteer scientists and technologists via the web. These dedicated but overtaxed officials decide which of the million-plus patent applications currently in the pipeline to approve. Their decisions help determine which start-up pioneers a new industry and which disappears without a trace. Patent examiners have traditionally worked in secret, cut off from essential information and racing against the clock to rule on lengthy, technical claims. Peer-to-Patent broke this mold by creating online networks of self-selecting citizen experts and channeling their knowledge and enthusiasm into forms that patent examiners can easily use.

Peer-to-Patent shows how policymakers can improve decisionmaking by harnessing networks to public institutions. By encouraging, coordinating, and structuring citizen participation, technology can make government both more open and more effective at solving today's complex social and economic problems. Wiki Government describes how this model can be applied in a wide variety of settings and offers a fundamental rethinking of effective governance and democratic legitimacy for the twenty-first century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Wiki Government by Beth Simone Noveck in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Public Affairs & Administration. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

Public Affairs & AdministrationPART ONE

COLLABORATIVE DEMOCRACY AND THE CHANGING NATURE OF EXPERTISE

CHAPTER ONE

PEER-TO-PATENT:

A MODEST PROPOSAL

You must do the things you think you cannot do.

—ELEANOR ROOSEVELT

PATENT LAW IS THE students' least favorite part of the semester-long class, Introduction to Intellectual Property, that I teach at New York Law School. In this survey course they learn about trademarking brands and copyrighting songs. But they also suffer through five jargon-filled weeks on how inventors apply to the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) to secure a twenty-year grant of monopoly rights. Despite the fact that patents signal innovation to the financial markets and investors and drive economic growth in certain industries, many dread this segment of the course.1 Patent applications are written in a special language; patentese is a member of the legalese language family that only the high priesthood of patent professionals understands. Even applications for the most mundane inventions are written in dense jargon. The patent application for the sealed crustless sandwich (aka the peanut butter and jelly sandwich patent), which sought to give Smuckers a monopoly on a process to crimp crusts, reads as follows:

Claim: 1. A sealed crustless sandwich, comprising: a first bread layer having a first perimeter surface coplanar to a contact surface; at least one filling of an edible food juxtaposed to said contact surface; a second bread layer juxtaposed to said at least one filling opposite of said first bread layer, wherein said second bread layer includes a second perimeter surface similar to said first perimeter surface; a crimped edge directly between said first perimeter surface and said second perimeter surface for sealing said at least one filling between said first bread layer and said second bread layer; wherein a crust portion of said first bread layer and said second bread layer has been removed.2

To help my students understand how patents further Congress's constitutional mandate to “promote the progress of science and useful arts,” I start by teaching the process by which the government decides whether to grant a patent.3 While this process has its special rules, the decision to award or withhold a patent is not unlike a thousand other decisions made by government every day, decisions that depend upon access to adequate information and sound science. Just as an official of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) must consult epidemiological studies to determine acceptable levels of asbestos or mercury in air and water, the patent examiner must obtain the relevant technological antecedents—known as prior art—to judge if an invention is enough of an advance over what preceded it to warrant a patent. The patent examiner effectively decides who will control the next BlackBerry or the next life-saving cancer drug.

The Patent Office employs 5,500 patent examiners.4 While the examiner might have an undergraduate degree in computer science, she does not necessarily know much about cutting-edge, object-oriented programming languages. She's not up on the latest advances coming out of Asia. She may not have seen anything like the patent application for bioinformatic modeling of the human genome or the application for a patent on poetry-writing software!5 She has not necessarily been to law school (you don't need a law degree to take the patent bar exam).6 She does not necessarily have a Ph.D. in science, and there is little opportunity on the job for continuing education. As an expert in patent examination, she is not and is not expected to be a master of all areas of innovation.

To make things worse, the inventor is not legally required to give her any help—say, by providing background research.7 Indeed, the inventor has an incentive not to supply the Patent Office with prior art, since the examiner might use it to determine that the invention lacks sufficient novelty and thus to reject the application.8 Sometimes inventors deluge an examiner with background research, hoping the overworked official will be daunted by the task of sorting the wheat from the chaff. It is no wonder that even Thomas Jefferson, the first patent examiner, in 1791 sought outside help, consulting with University of Pennsylvania chemistry professor Joseph Hutchinson before issuing a patent on an alchemical process for rendering seawater potable.9

Today the modern patent examiner works alone (or at most with a supervisor). Her primary resource is USPTO databases (known as East and West) of old and foreign patents, patent applications, and the prior art citations they reference.10 On average, she has just fifteen to twenty hours to research the patent application and write up her findings.11 Worse yet, her supervisor (with Congress in the background) is breathing down her neck to move on to the next application in the backlog of a million pending applications.12 Applicants wait upward of three years (and in certain fields closer to five years) to receive their first notice from the Patent Office, and that's usually just the beginning of a series of communications that will be exchanged before the patent is finally granted or rejected.

Even with more time, patent offices around the world still would not have access to the information they need. To know if a particular inventor is the progenitor of a chemical compound or software program, the examiner has to scour the literature. Government patent offices naturally have access to the historical corpus of patents, and they have access to excellent and up-to-date journals, but the information needed is not always found in traditional government or academic sources. Inventors in cutting-edge fields may discuss their work on the web rather than in print. John Doll, the U.S. commissioner of patents, complains of the dispersed databases and inconsistent search protocols that impede examiners' efforts to decide whether an invention is new, useful, and nonobvious—in a word, patentable.13 The result is an inefficient, inaccurate process: of the 2 million patents in force in the United States, many would not survive closer scrutiny.14

All this got me to thinking. What if the patent examiner worked with the broader community? What if the public augmented the official's research with its own know-how? What if the scientific and technical expertise of the graduate student, industry researcher, university professor, and hobbyist could be linked to the legal expertise of the patent examiner to produce a better decision? What if, instead of traditional peer review, a process of open review were instituted, wherein participants self-select on the basis of their expertise and enthusiasm? What if, instead of a social network like Facebook, a scientific and technical expert network were built? I nicknamed this “peer-to-patent.” The online tools available today could be employed to connect the government institution and the increasingly networked public to collaborate on an ongoing basis.

Such a process is already happening outside of government. Some business and nonprofit organizations recognize that processes that were once the purview of an individual might usefully be opened up to participation from a larger group. Cancer patients, for example, provide medical information to each other via the Association of Online Cancer Resources website and its 159 associated electronic mailing lists. The website Patients Like Me allows patients to share information about their symptoms and the progress of their diseases. Patients Like Me also has data-sharing partnerships with doctors, pharmaceutical and medical device companies, research organizations, and nonprofits to encourage patients to supply information to those who are working to develop cures.

Other examples abound. Amazon's web-based Mechanical Turk project outsources the work of answering simple questions, such as tagging people and places in pictures, measuring the size of molecules in a microscopic image, identifying land mines from photographs, and creating links to or from a Google map. YouTube depends on amateurs to post video content. Volunteers populate the Internet Movie Database (IMDb), which offers information about close to one million movie titles and more than two million entertainment professionals.15 Almost 30,000 Korean-speaking citizen-journalists report on stories for OhMyNews.com, where “every citizen is a reporter.”16 Korean speakers also answer each other's search queries via the Naver search engine, which far outpaces the popularity of such algorithmic search engines as Google and Yahoo!17 The Mozilla Corporation, maker of the Firefox browser, enlists the help of several thousand of its 180 million users to work on marketing campaigns, respond to queries on Mozilla message boards, write or edit documentation for developers, and even create the software code for the browser.18

More than 9,000 companies participate in technology giant SAP's global partner networks, and 1.2 million individuals participate in its online discussion communities, which are designed to generate innovation for the firm while making individuals more successful at their jobs.

Inspired by these examples, once the spring 2005 term ended, I wrote up a posting for my blog entitled “Peer-to-Patent: A Modest Proposal.”19 I proposed that the Patent Office transform its closed, centralized process and construct an architecture for open participation that unleashes the “cognitive surplus” of the scientific and technical community. I called on the Patent Office to solicit information from the public to assist in patent examination and, eventually, to enlist the help of smaller, collaborating groups of dedicated volunteers to help decide whether a particular patent should be granted. Through this sort of online collaboration, the agency could augment its intelligence and improve the quality of issued patents. “This modest proposal harnesses social reputation and collaborative filtering technology to create a peer review system of scientific experts ruling on innovation,” I wrote. “The idea of blue ribbon panels or advisory committees is not new. But the suggestion to use social reputation software—think Friendster, LinkedIn, eBay reputation points—to make such panels big enough, diverse enough, and democratic enough to replace the patent examiner is.”

Just as I posted my thought experiment the phone rang. Daniel Terdiman, a reporter for Wired News, was trolling for stories. “Heard anything interesting?” he asked. I reeled off three or four initiatives of various colleagues. “That's all well and good, but what are you up to?” Daniel probed, hoping I might have something to report. “Catching up on my blog and making improbable proposals to revolutionize the Patent Office, improve government decisionmaking, and rethink the nature of democracy,” I modestly replied.

On July 14, 2005, Wired News ran an article titled, “Web Could Unclog Patent Backlog.”20 As a reporter who wrote about videogames, not government, Daniel was uninhibited about calling the patent commissioner for a quote. Commissioner John Doll responded: “It's an interesting idea, and an interesting perspective.” Peer review, he added, “is something that could be done right now, and I'm a little surprised that somebody hasn't started a blog” for that purpose.

THE MODEST PROPOSAL TAKES OFF

The day the article appeared, Manny Schecter, the associate general counsel and managing attorney for intellectual property at IBM, sent me an e-mail: “I saw the story on Peer-to-Patent. We should talk.” Manny Schecter, Marian Underweiser, and Marc Ehrlich are known as the 3Ms of the intellectual property law department at IBM. Responsible for the company's 42,000 patents (28,000 in the United States alone), these three senior attorneys and their staff ensure that IBM continues its unbroken fifteen-year streak as the holder of the largest patent portfolio in the world. The firm now receives between 3,000 and 4,000 U.S. patents each year. In addition to strengthening the competitive position of IBM's products, these patents generate $1 billion annually in licensing fees from other businesses wishing to incorporate IBM's scientific inventions into their products and services. The size of IBM's patent portfolio signals to the market that the firm is an innovator, which may be responsible for its rising share price and increased shareholder value.21

As the USPTO's biggest client, IBM is one of the companies with the most to gain from an efficient patent system. It also stands to lose if the patenting process breaks down. With the pace of patent examination out of sync with the pace of innovation, firms like IBM are forced to wait ever longer for patents. And these innovations, on which their licensing strategies depend, may even turn out to be invalid. In addition, critics charge that the granting of undeserved patents, in combination with growing uncertainty over patent quality, has led to an increase in costly litigation. Patents provide a license to sue others for damages for using a patented invention. Companies with deep pockets, such as IBM, are more likely to be sued for patent infringement than smaller firms. Software patents, which represent the bulk of IBM's portfolio, are more than twice as likely as other patents to be litigated.22 The cost of defending such a suit, even for the victorious, makes the game not always worth the candle, especially when the alternative is to pay the plaintiff a five- or six-figure fee.

The 3Ms, therefore, had been contemplating ideas for patent reform that were similar to Peer-to-Patent. The company had been experimenting internally with technology for distributed collaboration for a long time, and senior executives credit IBM's rescue from the brink (it is one of the 16 percent of large companies tracked from 1962 to 1998 to have survived) to the digitally aided development of a culture of collaboration.23

IBM's lawyers were intrigued by the simplicity and promise of the Peer-to-Patent proposal, particularly since it could be implemented, at least as a pilot, without legislative or Supreme Court action. By spring 2006 they were ready to help the idea become reality. The 3Ms at IBM offered a research grant to New York Law School to allow me to (ironically) take a break from teaching Introduction to Intellectual Property and to flesh out the blog posting into a design for a practical prototype. Little did I know that by yielding to the temptation of a semester off to write a research paper I would end up launching an experiment to improve the flow of information to the Patent Office and running the government's first open social networking project.

In short order, corporate patent counsel at the major technology firms began to hear about Peer-to-Patent, and Microsoft joined the project with a commitment to submit patents for public review and to contribute much-needed additional sponsorship. After all, it would smack of regulatory capture and delegitimize the work if the largest customer of the Patent Office were to be the sole supporter, designer, and funder of a plan to reform it. Then came Hewlett-Packard, followed by Red Hat, General Electric, CA (Computer Associates), and finally Intellectual Ventures, the invention company founded by former Microsoft chief technology officer Nathan Myhrvold. These companies not only offered to submit their patent applications through this process but also contributed money to the development of the legal and technical infrastructure. In addition, New York Law School received support from the MacArthur Foundation and the Omidyar Network, the organization that channels the philanthropic activities of eBay founder Pierre Omidyar.

Dozens of lawyers, technologists, and designers gave their time and expertise to refining the design of the project. The result was a series of workshops at Harvard, Yale, Stanford, the University of Michigan, and New York Law School during 2006–07. The planning of Peer-to-Patent created educational opportunities for New York Law School students, who practiced law reform and acquired professional skills by running the project at every stage. They produced educational videos about patent law and prior art (think Schoolhouse Rock for the patent system). They wrote the directions for each page of the website, explaining to new users how to find and upload prior art in connection with a patent application or how to comment on prior art submitted by others. Students also drafted privacy and copyright policies, terms of use, and solicitations to inventors to invite them to submit their applications. Above all, they learned how to work as a team, using technical, legal, and communication tools to implement a solution to a complex problem in the real world.

FIGURE 1-1. PEER-TO-PATENT HOME PAGE AT WWW.PEERTOPATENT.ORG

Most important, despite the first-...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part One: Collaborative Democracy and the Changing Nature of Expertise

- Part Two: Peer-to-Patent and the Patent Challenge

- Part Three: Thinking in Wiki

- Notes

- Index

- About the Author

- Back Cover