eBook - ePub

Governing the Nile River Basin

The Search for a New Legal Regime

- 150 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The effective and efficient management of water is a major problem, not just for economic growth and development in the Nile River basin, but also for the peaceful coexistence of the millions of people who live in the region. Of critical importance to the people of this part of Africa is the reasonable, equitable and sustainable management of the waters of the Nile River and its tributaries.

Written by scholars trained in economics and law, and with significant experience in African political economy, this book explores new ways to deal with conflict over the allocation of the waters of the Nile River and its tributaries. The monograph provides policymakers in the Nile River riparian states and other stakeholders with practical and effective policy options for dealing with what has become a very contentious problem—the effective management of the waters of the Nile River. The analysis is quite rigorous but also extremely accessible.

Written by scholars trained in economics and law, and with significant experience in African political economy, this book explores new ways to deal with conflict over the allocation of the waters of the Nile River and its tributaries. The monograph provides policymakers in the Nile River riparian states and other stakeholders with practical and effective policy options for dealing with what has become a very contentious problem—the effective management of the waters of the Nile River. The analysis is quite rigorous but also extremely accessible.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 |

The Political Economy of Transboundary Water Resource Management in Africa |

Most African countries have territory that is located in at least one transboundary water basin (see, for example, Lautze and Giordano 2005, p. 1053), and about 62 percent of the continent's land mass is covered by transboundary water basins (Wolf and others 1999, p. 392). Because of the pervasiveness of transboundary water basins in the continent, “African water management is also, by definition, transboundary water management” (Lautze and Giordano 2005, p. 1054). Hence most water law on the continent has, historically, been transboundary water law.

One can begin the study of water management in Africa by taking a look at existing legal regimes that regulate the allocation of water across the continent. Ordinarily, that would lead one to those institutional arrangements that deal with transboundary water basins—that is, transboundary water law. African transboundary water law consists of agreements and treaties that were concluded in both colonial and postcolonial periods, many international water law conventions and treaties, and various customs and traditions that have, throughout history, regulated water use. To date, researchers have identified “more than 150 agreements, treaties, protocols, and amendments spanning over 140 years and involving more than 20 African basins” (Lautze and Giordano 2005, p. 1054).

During the colonial period, European countries that undertook the development and implementation of transboundary water agreements often did so not to ensure the fair allocation of water to benefit the African populations but to maximize European objectives in the colonies. As a consequence, the settling of boundaries between territories claimed by one European colonizer or another often dominated some of these agreements. For example, the 1891 Anglo-Italian protocol (officially referred to as the Protocol between the Governments of Great Britain and Italy, for the Demarcation of Their Respective Spheres of Influence in East Africa, from Ras Kasar to the Blue Nile) was designed by the two colonial powers not only to deal with water issues but also to settle the boundary between Italian Eritrea and British Sudan. The 1902 Anglo-Ethiopian treaty (Treaties between the United Kingdom and Ethiopia and between the United Kingdom, Italy, and Ethiopia relative to the Frontiers between the Soudan, Ethiopia, and Eritrea) also deals with boundary determination: the treaty aimed to settle the boundary between Sudan, which was at the time a British colony, and Ethiopia.

Jonathan Lautze and Mark Giordano (2005, pp. 1075–87) provide a relatively comprehensive list of African transboundary water agreements and treaties. Our interest in this monograph is not to delve into all the water agreements or into all the continent's water basins. Instead, we take a look at the agreements surrounding the Nile River basin that have regulated the allocation of its waters. Specifically, we provide an overview of the Nile Waters agreements—the 1929 Anglo-Egyptian treaty and the 1959 bilateral agreement between Egypt and Sudan, which the two countries claim to be the main legal framework for the Nile River basin.1 Today's Nile River riparians, except for Egypt and the Republic of Sudan, consider these agreements anachronistic holdovers from the colonial era and want them abrogated and replaced by a new international watercourse legal regime that enhances equity in the allocation of the Nile River's waters. Egypt and Sudan, however, insist that the existing Nile Waters agreements be maintained or that, in the event a new legal regime is established, Egypt's historical rights—those granted by the original agreements—should be honored.2

Although the Nile Waters agreements specifically mention Egypt's “acquired rights,” that virtually all upstream riparian states have renounced these agreements and do not consider them binding brings into question the validity of Egypt's claims.3 All property rights are relative, and treaties or other agreements may grant rights only as between those states that are actually bound by the treaties granting such rights and cannot do so relative to parties that are not bound by the treaties.

The Nile River basin's existing legal arrangements do not provide the wherewithal for the effective management of the basin's multifarious problems, which include the allocation of water, climate change, ecosystem degradation, and resource sustainability. We provide guidelines for the construction of an effective and viable legal mechanism that is capable of achieving fairness and sustainability in the allocation and utilization of the waters of the Nile River, as well as meeting the needs of the basin's economies, which are searching for ways to improve the living standards of their citizens. Such an agreement, we believe, would be acceptable to all riparian states.

Here we examine the failure of the countries of the Nile River basin to provide a legal regime that is acceptable to all and provides the necessary mechanisms for the equitable, fair, reasonable, and sustainable utilization of the waters of the Nile River.4 In chapter 2, we provide an overview of the physical characteristics of the Nile River, its tributaries, and sources. We also provide information on the river's riparian states and briefly examine various activities, such as agriculture, that affect water use in the basin. Finally, we examine the impact of climate change on the basin, generally, and water use, in particular.

In chapter 3, we explore various historical events that have contributed to the nature of conflict, specifically that related to the use of water, in the Nile River basin. For example, we take a look at how the U.S. Civil War created opportunities for the development of cotton production in the Nile River basin, significantly changed the political economy in the region, and set the stage for the conflict that currently afflicts the basin.

In chapter 4, we examine the Nile Waters agreements, which are considered a key to understanding the basin's present conflict. Although the downstream riparian states argue that these bilateral treaties represent the basin's legal regime, the upstream states reject that claim, argue that they are not bound by them, and seek to produce a new inclusive legal framework.

Chapter 5 is devoted to an examination of theories of treaty succession and their possible impact on governance in the Nile River basin. Of special interest is the Nyerere doctrine and how it was used by Britain's former colonies to justify their rejection of treaties that were entered into on their behalf by Britain.

In chapter 6, we examine international water law and its implications for governance in the Nile River basin. Specifically, we examine the UN Convention on the Law of Nonnavigational Uses of International Watercourses and determine the types of insights that it can provide for the Nile River basin countries as they struggle to develop an inclusive legal framework for the basin.5

In 1999 the Nile Basin Initiative was signed by the Nile River basin riparian states (except Eritrea) as a mechanism to enhance the equitable, fair, and sustainable utilization of the waters of the Nile River. In chapter 7, we examine the initiative and its relevance to the effective resolution of water-related issues in the Nile River basin.

Chapter 8 is devoted to an examination of the Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFA). In taking a look at this new agreement, we try to resolve the question of whether it can serve as the inclusive legal instrument that would finally bring an end to the struggle between the upstream and downstream states over how to allocate the waters of the Nile River.

In chapter 9, we review the tumultuous relationship between Egypt and Ethiopia, which over the years has had a significant impact on water-related conflicts in the basin. Chapter 10 is devoted to an examination of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, a project that is currently under way and is expected to have a significant impact on the demand for and supply of water in the Nile River basin.

Finally, in chapter 11, we suggest a way forward for the Nile River riparian states. Specifically, we conclude from our study that all relevant stakeholders—the upstream and downstream riparians—should engage in negotiations to produce a new inclusive treaty that would provide them with an effective legal mechanism for regulating the use of the waters of the Nile River.

Our goal is not merely to be critical of the current legal regime—the Nile Waters agreements—or to advocate the development and implementation of legal frameworks that would jeopardize the livelihoods of the people of Egypt and the Republic of Sudan or any other riparian state. Instead, we seek to show that inclusive negotiations would produce a legal regime capable of providing an environment leading to equitable, fair, and reasonable management of the Nile River waters and the peaceful coexistence of the populations of the states that share this common resource.

1. Officially, Exchange of Notes between His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom and the Egyptian Government in Regard to the Use of the Waters of the Nile River for Irrigation Purposes (with Seven Diagrams), May 7, 1929, L.N.T.S. 2103; and United Arab Republic and Sudan Agreement (with Annexes) for the Full Utilization of the Nile Waters, Cairo, November 8, 1959, 6519 U.N.T.S. 63. The short forms are used throughout this volume.

2. Although treaties grant rights, those rights are granted as between those states that are parties to the treaties and/or are bound by them. Since the upstream riparian states have made it clear that, as nonparties to these agreements, they are not bound by them, the validity of these rights is in question. Hence, they do not recognize the “historical rights” claimed by both Egypt and the Republic of Sudan.

3. See chap. 1, para. 2, of the 1959 bilateral agreement between Egypt and Sudan.

4. A major problem here is that it is not possible to maintain current allocations—that is, those provided by the Nile Waters agreements—and still increase access to the waters of the Nile River for the upstream riparian states. Equity and fairness necessarily imply trade-offs, which must involve a certain level of sacrifice by both Egypt and the Republic of Sudan.

5. UN Convention on the Law of the Nonnavigational Uses of International Watercourses, New York, May 21, 1997, G.A. Res. 51/229, U.N. Doc. A/RES/51/229.

2 | Physical Description of the Watercourse and Basin States |

The Nile River basin consists of complex ecosystems that are characterized by “high climatic diversity and variability, a low percentage of rainfall reaching the main river, and an uneven distribution of its water resources” (NBI 2012, p. 26). It is home to thousands of plant and animal species, many of which are endemic to the basin.

The Nile River basin's environmental resources and its water provide the basin's diverse peoples with a rich variety of goods and services and contribute significantly to the region's gross domestic product. The basin's system of waterways and wetlands provides both a flight path and a destination for migratory birds from other parts of the continent.

For many years, the Nile River basin's natural resource base has been threatened, and continues to be threatened, by various pressures, including agriculture, population increases, urbanization, invasive species, bushfires, mining and quarrying, climate change, and natural disasters. Although several game, wildlife, and forest reserves, as well as national parks, have been established to protect and conserve the Nile River basin's resources and its unique ecosystems, degradation remains a major problem for the basin (NBI 2012). Rapid degradation of the basin's ecosystems has become an important concern for many of the basin's states. Unfortunately, population pressures, relatively weak governments, dysfunctional legal and institutional frameworks, and poor public policies in the riparian states continue to constrain and endanger ecosystem management in the basin.

The irrigation of agricultural fields in Egypt and the Republic of Sudan represents the single most important use of the waters of the Nile River—primarily because these two riparian states have the most developed irrigation systems in the basin.1 In recent years, however, many upstream riparian states have either developed or are in the process of developing the capacity to more effectively harvest and utilize the Nile River's waters for national development.2 As the upstream riparians develop the capacity to challenge the downstream states for the allocation of the river's “renewable discharge” (NBI 2012, p. 26), issues of equitable, fair, and reasonable use of the waters of the Nile River, as well as the sustainability of the basin's ecosystem, are likely to intensify.

The Nile River and Its Basin

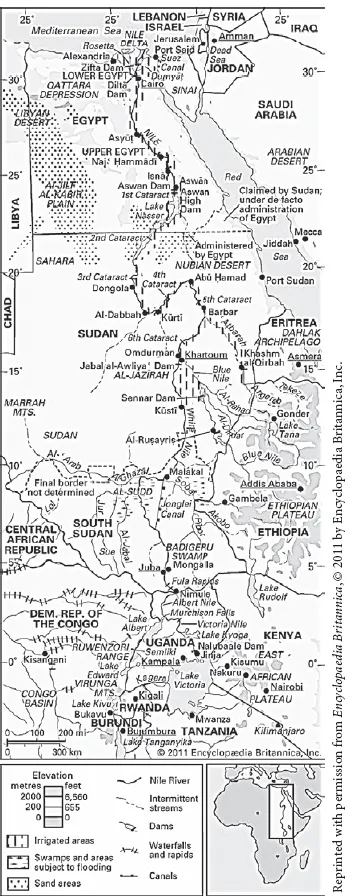

The Nile River is the world's longest watercourse, measuring 4,160 miles (6,695 kilometers) and flowing over thirty-five degrees of latitude (Collins 2002, p. 11; see also figure 2-1). Its basin covers an area of about 1.227 million square miles (3.18 million square kilometers), approximately 10 percent of the African continent, and is shared by eleven countries of the river's basin.3 The river's southernmost source is a spring in Burundi called Kikizi (see figure 2-1). The Kikizi spring and others like it eventually coalesce into rivers. Two of these rivers, the White Nile, whose ultimate sources are in Burundi, and the Blue Nile, which originates in the Ethiopian highlands, are the main sources of the Nile River's waters. The White Nile, which flows through equatorial Africa, also runs through Lakes Albert and Victoria, the latter of which is shared by Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. The White Nile provides about 15 percent of the waters that flow into the Nile River, and the Blue Nile, whose tributaries include the Abbay, Sobat, and Atbara Rivers, provides 85 percent of the water flowing into the Nile River as measured at Aswan in Egypt (NBI 2012, p. 36).4

Figure 2-1. The Nile River Basin

The Nile River basin consists of “distinct regions that correspond to the different typography through which it passes on its long journey out of equatorial Africa to the Mediterranean Sea” (Collins 2002, p. 1; see also NBI 2012; and figure 2-1). In its southernmost source, the Nile River starts as many springs and rivers, “plunges down as the Bahr al-Jabal, the Mountain River, into the swamps of the southern Sudan known as the Sudd, from which it emerges into the broad expanse of the White Nile and its great meeting at Khartoum with the Blue Nile from Ethiopia” (Collins 2002, p. 1). From Khartoum, the Nile River flows to the Nile delta and into the Mediterranean Sea (Sutcliffe and Parks 1999, p. 1; see also figure 2-1).

From Burundi and Rwanda, the many rivers and springs that form various tributaries of the Nile River converge into the Kagera River, which flows into Lake Victoria, the world's second-largest freshwater lake (Collins 2002, p. 2). Within this plateau are other lakes, including Lakes George, Edward, Albert, and Kyoga. Although these lakes contribute significantly large amounts of water, the Nile River flows directly from the northern tip of Lake Victoria as the Victoria Nile. The latter “pours over the Owen Falls Dam and then into Lake Kyoga, after which, in a spectacular drop, it crashes down from the lip of the great African Rift Valley at Kabarega Falls (formerly Murchison Falls) to its bottom at Lake Albert,” and strengthened by waters from several lakes, notably, Lakes George, Edward, and Albert, “the Victoria Nile flows out of the Lake Plateau as the Albert Nile to the border of Uganda at Nimule, where it becomes the Bahr al-Jabal, or the Mountain River” (Collins 2002, p. 2; see also figure 2-1).

The Mountain River struggles slowly through hundreds of miles of swampland and eventually flows into Lake No, a relatively shallow water body, whose main outlet is the White Nile. The latter flows toward the Mediterranean Sea, and some seventy-five miles from its start at Lake No, its flow is strengthened significantly by waters from the Sobat River, which originates in Ethiopia. Now totally replenished by waters from the Sobat, the White Nile flows north for nearly five hundred miles through South Sudan and the Republic of Sudan and eventually joins the Blue Nile at Khartoum and becomes the Nile River (see figure 2-1).

The Blue Nile originates in the Ethiopian highlands at about six thousand feet. The Blue Nile, called the Great Abbai in Ethiopia, flows out of the southern shore of Lake Tana, runs in a southeastern direction, drops over the Tisisat Falls, and...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- 1 - The Political Economy of Transboundary Water Resource Management in Africa

- 2 - Physical Description of the Watercourse and Basin States

- 3 - Setting the Stage for Conflict in the Nile River Basin

- 4 - The Nile Waters Agreements: A Critical Analysis

- 5 - Theories of Treaty Succession and Modern Nile Governance

- 6 - International Water Law and the Nile River Basin

- 7 - The Nile Basin Initiative

- 8 - The Cooperative Framework Agreement: A New Legal Regime for the Nile River?

- 9 - Egypt, Ethiopia, and the Nile River

- 10 - The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam

- 11 - Governing the Nile River Basin: A Way Forward

- References

- Index

- Back Cover

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Governing the Nile River Basin by Mwangi Kimenyi,John Mbaku in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & African History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.