![]()

1

MONTGOMERYSHIRE

PEOPLE, PLACES AND OCCUPATIONS

The focus of this study is the county of Montgomeryshire. This chapter will set the scene for forthcoming investigations, describing the main features of this part of Wales, namely the land, industries and people. There will be a description of the topography and changes that occurred in the countryside as industrialisation took place in hitherto market towns. Demographic features including occupational status and sizes of labour forces will be noted, and the justice system seen by people in court will be interpreted.

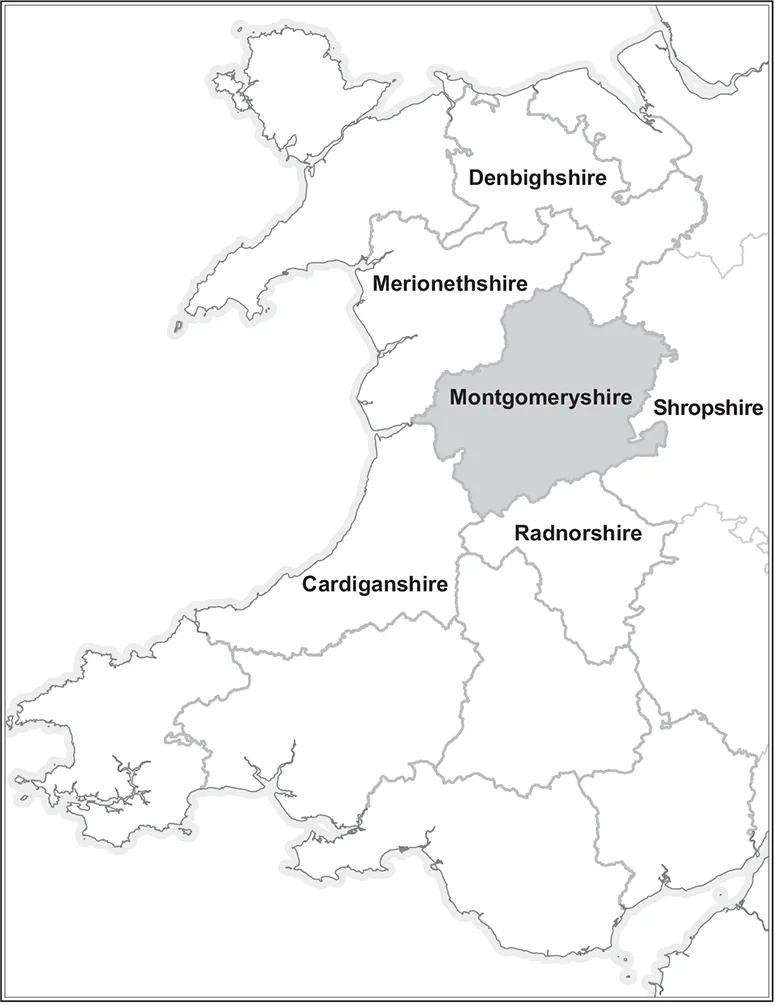

THE COUNTY

Montgomeryshire is now part of the modern county of Powys, but before local government changes in 1974 it was a county in its own right. It was the largest county in north and mid-Wales, and the second largest in Wales as a whole (Figure 1.1). Flat land pushes into the hills in the north-east forming a gateway into the area, and the low-lying land that accompanies the rivers Banwy and Vyrnwy provides routes westwards. Another way into Montgomeryshire is also from the north-east, but this time following the valley of the river Severn in a south-westerly direction past Welshpool, Newtown and Llanidloes (Figure 1.2).

OCCUPATIONAL NATURE OF THE COUNTY

During the nineteenth century, the main industry in Montgomeryshire was agriculture, and approximately one-tenth of the produce of Wales came from the county. In the 1871 census, 11,004 persons aged over twenty years were of the agrarian class, which constituted a little over a quarter of that age group.1 In modern times, much of the western side of the county has been classified by the government as ‘severely disadvantaged’, being wetter and less fertile than the east.2 The same situation existed during earlier periods as John Marius Wilson wrote in 1874:

Figure 1.1 Montgomeryshire and its neighbouring counties.

Figure 1.2 Montgomeryshire: the valleys of the Severn, Banwy and Vyrnwy.

The surface, in most of the east, to the mean breadth of about 5 miles, is a mixture of rich vale and pleasant hill, luxuriant, warm and low; but the surface, all elsewhere, is prevailingly mountainous, moorish, bleak and wild.3

He did concede, however, that many western hills were wooded and surrounded by vales that afforded unexpected fertility. The main crops were oats, wheat and barley, with the first of these being the most produced, although by 1870 land under the plough was decreasing as stock breeding increased. New varieties of sheep were trialled, and dairy shorthorn and Hereford cattle became popular.4 Wilson wrote that about one-eighth of the land was arable, about one-third pasture and about half was common or waste. He observed a further disparity between the east and west:

Yet the farmhouses, in other parts than the east, are aggregately far from good – many of them timbered, and the cottages are very poor. The native cattle, a small, brindled short-legged breed, deep in the carcase, are kept on the inferior farms. The Devonshire and Herefordshire breeds abound on the best farms.5

Two examples of the well-off farmers in the east were widow Susan Powell of Buttington Hall, near Welshpool, and her neighbour William Beckerton. Both these farms were of over 300 acres and gave employment to a total of fifteen residential workers. The survival of this live-in form of labour was a feature of the county, a more traditional form of labour that had been lost in many English regions by this time.6

HEAVY INDUSTRY

Along with agriculture, manufacturing was present in the county, the chief business being the production of woollen items which had been ongoing since the middle ages.7 Originally, the trade was a cottage industry, with all the preparatory processes carried out by hand, and only the final ‘fulling’, or washing, of the cloth being done at a fulling mill (pandy in Welsh).8 It is said that in Montgomeryshire ‘nearly every farm had its weaving contingent and rents were half made from the making of flannel’.9 Daniel Defoe’s account of his traverses through the county during the 1720s does not mention any factories:

The River Severn is the only beauty of this county, which rising I say, out of the Plymlymon [sic] Mountains, receives instantly so many other rivers into its bosom, that it becomes navigable before it gets out of the county, namely at Welch Pool,10 on the edge of Shropshire. This is a good fashionable place, and has many English dwelling in it, and some very good families, but we saw nothing further worth remarking. The vales and meadows upon the banks of the Severn are the best of this county, I had almost said, the only good part of it.11

Fifty years later, Thomas Pennant observed the effects of the flannel industry while on his tour of Wales:

Llanidloes, a small town, with a great market for yarn, which is manufactured here into fine flannels, and sent weekly, by wagonloads to Welshpool… Welshpool, a good town, is seated in the bottom, not far from the castle [Powis Castle, seat of the Earl of Powis]. Great quantities of flannel, brought from the upper country, are sent from hence to Shrewsbury.12

The reference to Shrewsbury is very telling. The town had a monopoly on buying and selling Welsh cloth that began in Tudor times by an Act of 1565,13 and by the eighteenth century Montgomeryshire producers were totally dependent on the Shropshire drapers – a reflection of the poverty of the mid-Wales countryside, where the quick sale of cloth for ready cash meant the difference between existence and starvation. As well as this, the drapers helped weavers to buy raw materials, in some cases buying yarn for them and paying only for the weaving. By the end of the eighteenth century, local drapers emerged and eclipsed the Shrewsbury traders. When the Revd J. Evans travelled in the area at the end of the eighteenth century, he observed of Newtown:

It contains several streets and is in a flourishing condition. An extensive manufactory of flannel is carried on in the town, and in the parts adjacent. This article is got up in a masterly manner and employs the numerous poor of the town and neighbourhood… All the flannels here are the effect of manual labour: machinery has not found its way into north Wales.14

However, mechanisation did arrive, and investors in new machinery became powerful manufacturers.15 In 1818 John Aitkin noted: ‘Newton [sic] on the Severn, is the centre of a considerable woollen manufacture, especially of flannels of all qualities.’16

In 1871, about 22 per cent of the population aged over twenty years was involved in this industry, only a few percentage points less than agriculture.17 The manufacturing heartland was along the Severn the towns of Llanidloes, Newtown and Welshpool, facilitated by the accessibility of the valley. Indeed, both the county’s only canal and the railway line to Aberystwyth, were constructed along this route.18 Of the three centres of production, Newtown was the greatest, and was known as ‘the Leeds of Wales’ owing to the success of its factories.19 In 1833, Robert Parry wrote a ballad extolling its success and the prosperity it brought:

Oh what a blissful place! By Severn’s banks so fair,

Happy thine inhabitants, and wholesome is thine air.

Nine years long since last I’ve seen thee fled,

Ah! When departing my heart in grief has bled!

Thy lasses fair, and thy young men as kind,

Thy flannel fine and generous every mind,

But now, ’tis now I wonder most,

I see thy improvements; well can thy townsmen boast;

To London great, in short by the canal,

Thy flannel goes, as quick as one can tell,

And thence from there the flannel’s quickly hurled

To every part of Britain and the world.

Thy gaslight’s bright, thy new built houses high,

Thy factories lofts seem smiling on the sky.20

Although there had been a downturn in the industry’s prosperity after the 1830s, it was still a major employer in the town at the beginning of the 1870s.21 Investigation of the 1871 census show 300 woollen-cloth producers and 152 flannel manufacturers, and flannel workers living all around the town.22 There were pockets where the workers in these trades lived, generally in those quarters containing yards, sometimes known as shuts or courts. One of the main thoroughfares in Newtown was Park Street, and several yards were concealed behind it with access via narrow passages. Ten of these yards were investigated and 34 per cent of residents worked in the woollen or flannel industries. Across the town in a northerly direction was Russell Square, a small enclosed area with thirty-four residents stating an occupation. Eighty-eight per cent of them were flannel and wool workers. West of Russell Square, on the far side of the main shopping street was Kinsey Yard. Here 50 per cent were flannel and wool workers. Many of these areas have been demolished, but old photographs, maps and the remaining houses show building types that expanded during the Industrial Revolution. Some contemporaries considered them to be a cause of crime and vice, including close-packed, back-to-back, small terraced houses.23 The people of the Park Street yards had access to three wells and two pumps, and those living in Russell Square shared one well. Although the location of Kinsey Yard is not on any existing map, an idea about its whereabouts can be deduced from the census revealing that its residents had access to one pump. To the north of the town, across the river, lay Llanllwchaiarn and the industrial quarter known as Penygloddfa. Three yards were investigated here and it was found that 71 per cent of residents worked in the flannel or wool industries.

The flannel industry for which Newtown was famous also existed in Welshpool. A visitor to the town wrote in 1832 that it was: ‘A large and populous town and the appearances of opulence are very predominant throughout the place perhaps owing to the trade in Welsh flannel which is carried on here to a very great extent.’24

During the first half of the nineteenth century, housing for the workers grew up in parts of the town formerly occupied by gardens. The prosperity of the industry did not last and Table 1.1 shows the change in numbers of flannel manufacturers and merchants featured in trade directories.25 The demise of the industry in Welshpool has been attributed to strong competition by mills in Newtown and Llanidloes, although by the 1840s the industry was also failing in those towns.26 ...