- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

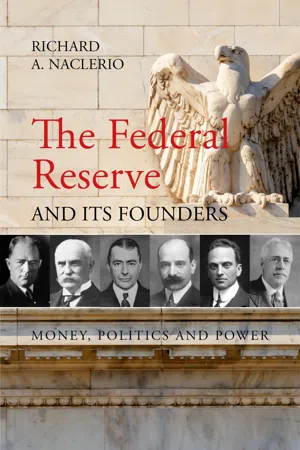

To fully understand the Federal Reserve and its role today we need to examine its origins and the men who founded it. Using extensive archival sources, Richard Naclerio investigates the highly secretive events that surrounded the Fed's creation and the bankers, financiers and tycoons that shaped both its organization and the role it was to play over the next century. The motivations of this handful of men who created the first draft of the Federal Reserve Act are explored, and the business ties and shared ideologies that bound them together revealed. A story of vested interest and the pursuit of power, the book sheds new light on the creation of one of the world's most important financial institutions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Federal Reserve and its Founders by Richard A. Naclerio in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Genesis

Historians often argue about what single civilizing occurrence had the most impact upon the history that succeeded it. The invention of the plow in ancient Egypt comes to mind. Or, it could be argued that the printing press was the largest historical game-changer. In terms of industry, the Sumerian ziggurat must be on the list, or for societal order, Hammurabi’s Code, which first systematized the law in ancient Babylon. In the modern era, the invention of the home computer must be in the conversation, as well as the smart phone, perhaps.

However, there is one historical event, which to an economic historian can be argued as the most impactful on all of human kind. Everything else pales in comparison to the change brought about in the social, legal, cultural, military, labour, gender, and any other compartment of the historical landscape by one single innovation: the invention of money. Money is the greatest civilizing factor in history, and its existence remains the cornerstone of all power throughout history. Without money, nothing is possible, and for those who have most of it, anything is possible.

Before currency, the barter system was the means for purchasing goods and services. We would trade things like wheat and wood, goats and oxen, for other things like pottery and jewellery, oats and daughters. But the problem with many of the things we would trade like wheat, oats, oxen, and even daughters is the fact that they all die. Goods and services were greatly limited by the fact that they did not last long. The wealth of an individual could not be measured by his ownership of goods or his ability to produce. Even property was subject to the weather, the elements, and population adjustments.

Then, around 1100 BCE, in the era of the Palestinian civilization, a society of people in modern-day central and western Turkey, changed history forever. The ancient Lydians perfected the metallurgy of gold, silver, copper and bronze and became the first to mint coins from these metals and to create the first uniform accounting and record keeping system for the purposes of disseminating currency. Humankind was no longer subject to the shelf life of their tradable goods and services and with currency, came one thing never before possible: the storage of wealth.

As history progressed, currency quickly became the major means for the purchase of all goods and services, and currency led to the development of banking. All civilizations and societies exhibited a banking industry in one form or another. However, this field was consolidated and dominated by Jews in the early middle ages. Not because of some presently existing racist stereotype, but because of a very old racist attitude against the Jewish faith. Banking was seen as a lowly occupation in the centuries when land was everything and the Church of Rome held dominion over most of Europe. At that time it was considered sinful to charge interest for any loan. Since Jews did not fall under the same religious restrictions that Christians did, they were free to enter this plebian industry known as “moneylending”, which they mastered among themselves. But, the church soon conceded to the boundless opportunities that banking had to offer and Europe became the centre of the financial universe for centuries to come, religious affiliation not withstanding.

In America, banking played a major role in the new republic’s inception. It would also be instrumental in changing the nation from what it was intended to be. The original structure of government, which was so closely tied to the founding fathers’ constitution, was based on the individual freedoms of American citizens. The true intent of America’s patriots was a commitment to a communal sense of neighbourly self-governance; their values of virtue and trust in each other reflected a disdain for self-promotion and the lust for profit, which today’s America seems not only to be completely infected with, but steadily reveres and feeds upon under the guise of an “American dream”. In economic terms, the Founding Fathers and American Patriots had a different understanding of what it meant to be a truly free American. It was not Herbert Spencer’s social Darwinism and his “survival of the fittest” mantra that far too many Americans think is the oil with which their country’s machinery works, but instead, a community of citizens, ruling themselves by committee. Nor was it François Quesnay’s laissez-faire economic template from Tableau Économique or Adam Smith’s “invisible hand”. The Founding Fathers, including Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, John Hancock and Benjamin Rush had a vision that was more akin to Thomas Paine’s, Common Sense, wherein individual freedom was best achieved and protected by a communal effort towards building a republic.

Original American patriotism was steeped in the notion that we should feed each other, police each other, and consult with each other. The power of the local committee was the linchpin of the Patriot ideal and it allowed power to flow through the land “from the farmer and the cobbler to the merchant and the landlord”. It was “a movement powerfully shaped by ordinary men, infused with ideals of mutual dependence and neighborly relations”. It relied on “the political powers of ordinary free colonists”, and it defended “popular presence as strongly as it defended representation”.1

With all these good intentions and lofty goals for post-Revolutionary America, it was currency and debt that proved to be the undoing of the Patriot ideal. To pay for the Revolutionary War, currency finance was adopted. In June 1775 America issued its first $2 million in paper money. In July it added another million, and then another $3 million in 1776. This currency was earmarked for circulation among the Patriot population of the Thirteen Colonies and was to be integrated into their already established practices guided by ideals of interdependence and unity, within a policy of “commitment to consent in the marketplace”. The Patriot Congress recommended new laws to be enacted to require creditors to accept these notes for all private and public debts.2

The Tory Party, entrenched in their conservative allegiance to Britain and its parliamentary procedure of imperial dominion over the colonies, would not accept the new Patriot currency and began to counterfeit it in order to lessen its value and impede the progress of the colonial war effort. Soon, refusal to accept the bills by predatory suppliers and merchants who were deemed as imperial sympathizers spread, as they also aggressively raised their prices. The new Patriot economy was marked for death, as “Men who sought a profit by weakening Patriot paper bills were guilty of the same greed and desire for power” as those who came before them, who resisted the Patriot ideal throughout the 1770s.3

The strength of the Tories in Congress led to Robert Morris’s appointment as the financier of the Revolution. Morris, a Pennsylvania congressman, had been accused of seizing and withholding a massive shipment of dry goods in the port of Philadelphia in order to await the further value depletion of the Patriot currency, so as to sell the goods at higher prices to more desperate citizens. He was even brought up on charges, arrested, and went to court for the monopolization of goods. However, the evidence proved that since people bought up his product so quickly, there must have been a proper demand for the prices he set, therefore there was no illegality, only greed, laced in his actions.4

Morris quickly formed a “money connection” by pursuing the wealthier businessmen of the nation and began to carry out his vision of a powerful commercial empire, dominated by the elite sect of the new nation that would replace the Patriot economy. He removed government backing from the Patriot currency, enacted a program of heavy taxation, deregulated anti-monopoly laws, and set about creating a new money that would secure the confidence of the rich, in which money would be private instead of public (that currency would be issued by individuals and/or the banks they represented; not the US government). Large denominations of new currency were issued and “a majority of the certificates were concentrated in the hands of a limited number of commercial men in the states north of Maryland”.5

These certificates were given value and Morris conspired with his monied allies to ensure that the new government would be indebted to him and his wealthy cohort. With this debt, came a strong central government, whose most important role was to pay the private creditors for the money they held. Thus, a strong lobby for the monied class was established and these men held control over the politicians running postwar America. The government was given the full authority to tax, which became its only option to pay back what Morris and the others had insisted to be both interest and principal, “all calculated on the face value of certificates often bought for a mere fraction of that amount”.6 The original Patriot vision for a currency that was to be distributed among the masses was gone, and the consolidation of currency into the hands of the wealthy few, their ability to loan it to a fledgling government (over which they had immense lobbying power), and their ensuing economic domination over America had begun.

By the 1790s the Founding Fathers went from battling creditors to battling each other over the existence of a central bank. Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin fought tirelessly to stop Alexander Hamilton from executing his plan for a central bank; Hamilton and his support of the First Bank of the United States was to set in motion an arduous process of controversy and embroiled debate surrounding central banking. A German banker by the name of James Rothschild was the bank’s financial backer and helped to create it. He was the most powerful banker in France at the time, and he was a member of the most powerful banking family in the world.

On paper, the central bank was not a bad idea. It acted to provide currency, as a depository for federal funds, to control state bank note issuances, and was the fiscal agent for the country. It also loaned money to private, commercial and industrial interests and paid the government money, as a bonus, for the privilege of holding massive amounts of federal funds for the bank’s use in making tremendous profits, interest and tax free.

What made central banks more palatable back then, was the fact that they were chartered. They would come into existence because there was a need for them at the time. The First Bank of the United States was necessary because of the debt the Republic had incurred after the Revolutionary War, and a financial plan was needed to pay back the creditors who held the loans and most of the currency. The federal government granted the bank’s charter for a twenty-year term, from 1791–1811.

This charter system was how all corporations existed at the time. If a need arose for a project, like a bridge or a dam, businessmen and developers would create a corporation to commence and complete the project for a profit, and the government would allow them to incorporate for a specified term for the sole purpose of completing said project. The given project would benefit the common good of a city, state, town, or the entire country. Once the term of the charter was up, hopefully after the project was completed, the corporation would either disband or be asked to start another project under another charter with another specified term. In the case of the central bank, it was chartered to get the nation out of debt. The principle behind these fixed-term charters was to guard against a company (or bank) that was big enough to complete a job of such magnitude becoming too financially influential and powerful to be kept properly regulated. So the government issued these term-limited charters to benefit everyone involved without allowing for the size and scope of the corporation to spiral out of control.7

After the Civil War, massive rebuilding projects proved to be a prodigious opportunity for corporations to gain more power and profit. Thus, corporate lawyers used the Fourteenth Amendment to gain traction for the advancement of their interests. The Fourteenth Amendment was enacted in 1868 to protect the rights of ex-slaves from States impeding them from seeking life, liberty, or property. However, shrewd corporate lawyers began to bring cases to the US Supreme Court that argued the rights of corporations to be equal to the rights of a newly freed slave.

In 1888 the Supreme Court ruled in Pembina Consolidated Silver Mining Co. v. Pennsylvania: “Under the designation of ‘person’ there is no doubt that a private corporation is included in the Fourteenth Amendment”.8 According to Mary Zepernick, the head of the Program on Corporations, Law, and Democracy, 307 cases were brought before the US Supreme Court under the Fourteenth Amendment between 1890 and 1910; 288 of them were brought by corporate attorneys and only 19 by African American ex-slaves.9

The First Bank of the United States did its job. The country was almost out of debt and the bank’s charter was up. However, the federal government enlisted central banking again, this time over the formation of the Second Bank of the United States. Why the need for another one? The First Bank was formed to help pay Revolutionary War debts, and its charter expired in 1811. The very next year the War of 1812 broke out. The United States military, unprovoked and in an expansionist effort, attacked the British and Indians in the North and Midwest. After this war, James Rothschild used Philadelphia banker and financier, Nicholas Biddle, to bid for the second bank’s existence. With Rothschild’s help, Biddle ended up forming the Second Bank of the United States, became its first president, and helped to create the powerful Independent Sub-Treasury System; another arm of private central banking.10

The Second Bank of the United States was chartered in 1816 to do the same job as the First – get the nation out of debt from war. The government used the bank to secure debt reduction so it did not have to put undue pressure on the existing money market of the country’s currency. The bank, under Biddle, set interest rates higher and reduced loan volume to accommodate the country’s payouts to defence contractors and other private bankers who had financed the war. The problem was that the new central bank, like the first one, did its job too well for its own good.11

In 1828, in his inaugural address, President Andrew Jackson pledged to eliminate the national debt under his administration. During his campaign, he accused the Second Bank of the United States of engaging in anti-Jacksonian politics. Jackson’s plan was to pay off the country’s existing debt by 1833, sell its shares in the central bank, and not renew its charter, which was up in 1836. He figured it would be counter-productive to sign another charter for a central bank, if the country was going to be out of debt. Historically, the role of a central bank is that simple. It exists to benefit the citizens and their government by means of aiding the economy so as to free the nation from debt. The problem for the bank is that if there is no debt, it is no longer necessary. The founders of the Federal Reserve System knew this.

Biddle proposed plan after plan to President Jackson. They benefited the public, the country’s creditors, the government and the bank. They were sound ideas for the nation to end its debt by Jackson’s deadline. However, Biddle wanted to be rewarded for doing a good job by having his charter renewed for a further fifteen or twenty years.12 What Biddle had not understood was that the US government had given him and his banking colleagues the privilege of aiding their country in its time of need, and had paid them handsomely to do so. Also, Biddle and his Rothschild backer were certainly not the only bankers who could have done what they did. They were given an op...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- About the Author

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. The Genesis

- 2. The System

- 3. The Island

- 4. The Politician: Nelson W. Aldrich

- 5. The Architect: Paul M. Warburg

- 6. The Lieutenant: Benjamin Strong, Jr

- 7. The Emissary: Henry P. Davison

- 8. The Professor: A. Piatt Andrew

- 9. The Farm Boy: Frank A. Vanderlip

- 10. The Panic, the Pirate, and Pujo

- 11. The War

- 12. The Journalist: Bob Ivry

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography