eBook - ePub

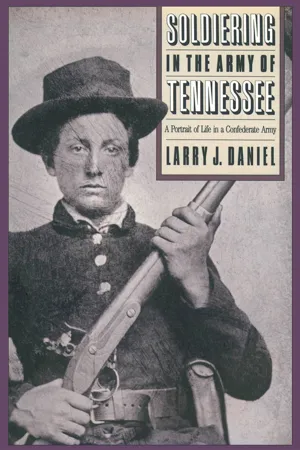

Soldiering in the Army of Tennessee

A Portrait of Life in a Confederate Army

- 249 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In Soldiering in the Army of Tennessee Larry Daniel offers a view from the trenches of the Confederate Army of Tennessee. his book is not the story of the commanders, but rather shows in intimate detail what the war in the western theater was like for the enlisted men. Daniel argues that the unity of the Army of Tennessee — unlike that of Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia — can be understood only by viewing the army from the bottom up rather than the top down.

The western army had neither strong leadership nor battlefield victories to sustain it, yet it maintained its cohesiveness. The "glue" that kept the men in the ranks included fear of punishment, a well-timed religious revival that stressed commitment and sacrifice, and a sense of comradeship developed through the common experience of serving under losing generals.

The soldiers here tell the story in their own rich words, for Daniel quotes from an impressive variety of sources, drawing upon his reading of the letters and diaries of more than 350 soldiers as well as scores of postwar memoirs. They write about rations, ordnance, medical care, punishments, the hardships of extensive campaigning, morale, and battle. While eastern and western soldiers were more alike than different, Daniel says, there were certain subtle variances. Western troops were less disciplined, a bit rougher, and less troubled by class divisions than their eastern counterparts. Daniel concludes that shared suffering and a belief in the ability to overcome adversity bonded the soldiers of the Army of Tennessee into a resilient fighting force.

The western army had neither strong leadership nor battlefield victories to sustain it, yet it maintained its cohesiveness. The "glue" that kept the men in the ranks included fear of punishment, a well-timed religious revival that stressed commitment and sacrifice, and a sense of comradeship developed through the common experience of serving under losing generals.

The soldiers here tell the story in their own rich words, for Daniel quotes from an impressive variety of sources, drawing upon his reading of the letters and diaries of more than 350 soldiers as well as scores of postwar memoirs. They write about rations, ordnance, medical care, punishments, the hardships of extensive campaigning, morale, and battle. While eastern and western soldiers were more alike than different, Daniel says, there were certain subtle variances. Western troops were less disciplined, a bit rougher, and less troubled by class divisions than their eastern counterparts. Daniel concludes that shared suffering and a belief in the ability to overcome adversity bonded the soldiers of the Army of Tennessee into a resilient fighting force.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Soldiering in the Army of Tennessee by Larry J. Daniel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Certainly a Rough Looking Set

In September 1863 two divisions of Lieutenant General James Long-street’s corps of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia reinforced the Army of Tennessee. One of Bragg’s cannoneers was stunned when he first laid eyes on the veterans from Virginia. “Our first impression was partly caused by the color of their uniform, but more by its uniformity, and the superior style of their equipments, in haversacks, canteens, and knapsacks. This contrast between them and Gen’l Bragg’s motley, ragged troops was striking in the extreme. If this command was a specimen of Lee’s troops, they are certainly superior to the troops of the Army of Tennessee, in dress.”1

The difference between the soldiery of the two armies was more than cosmetic. Thomas L. Connelly asserts that the identities of the Army of Tennessee and the Army of Northern Virginia have been stereotyped—the former associated with the roughness of the Old Southwest and the latter as “an army of planter’s sons.” Connelly continues, “For example, in the Virginia army, a man of the coarseness of Jubal Early was considered something of an oddity. In the Tennessee army, a tobacco-chewing, cursing, hard-drinking general such as Benjamin F. Cheatham was an accepted fact.”2

Seventeen-year-old William Shores, drummer boy of the Sixth Arkansas, was mortally struck in the Battle of Murfreesboro, with a gunshot wound to the stomach. (Eleanor S. Brockenbrough Library, Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond, Va.)

In many respects, the coarseness of a Cheatham or a Nathan Bedford Forrest represented the norm for the western army. The genteel plantation living of the Virginia Tidewater was foreign to the region. Henry Stanley estimated that one-fifth of his regiment, the Sixth Arkansas, were educated gentlemen, but the balance were rough and untaught, knife-toting backwoodsmen. When an Alabamian first viewed Terry’s Texas Rangers, he had to admit that they were “certainly a rough looking set.” When one examines the postwar questionnaires of Tennessee troops who served in the Army of Tennessee, a composite profile quickly emerges. The typical enlistee was a nonslaveholding man in his early twenties, born in a small log cabin, with limited public education, who farmed for a living.3

In their various attitudes toward soldiering, the differences in the character of the westerners were more subtle. In relating comments about rations, drill, pastimes, and the like, their statements often mirrored those of their eastern counterparts. The western boys, however, had more rough edges, less self-discipline, and fewer of the gentler refinements. After Shiloh, Brigadier General Manigault stated that the army was excessively undisciplined. Although this laxness evaporated somewhat as the men were transformed into hardened veterans, it still remained a problem. As late as the Atlanta Campaign, Lieutenant Robert Gill of the Forty-first Mississippi conceded: “Their [William T. Sherman’s] army is as well united as ours and better disciplined.” For example, the venereal disease rate in the Army of Tennessee far surpassed that of its sister army in Virginia, a point to be discussed later but one that relates directly to army discipline and control. In one respect, this roughness worked to advantage for there was generally a less pronounced class distinction in the West, resulting in little evidence of strife between the refined and lower classes. Fully three-fourths of the Tennessee questionnaire respondents indicated virtually no awareness of class strife before the war. This, perhaps, may have made the transition to army life smoother than in the Army of Northern Virginia.4

A reporter for the Richmond Dispatch, who had previously viewed the troops of Virginia and the Carolinas, arrived in Corinth in the spring of 1862 after the Battle of Shiloh. He immediately noticed that the western soldiers lacked the discipline and military rigidity characteristic of those in the Army of Northern Virginia. The officers appeared to him simply to be the toughest men in each outfit. The troops from Louisiana were “small, wiry, quick as squirrels in their motions and thoroughly Gallic in their habits and associations. The men of Alabama and Mississippi are taller, [and] as a general thing less cosmopolized,” he observed. The men from Tennessee, Kentucky, Arkansas, and Missouri exhibited a “Sort of don’t-care-a-damativeness.” The clothing of the troops was distinctive in its lack of uniformity. “Here you see the well dressed gentleman with nothing to mark the soldier but the cartridge box, body belt and shot gun. There is a group of Mississippi boatmen in their slouched hats, cowhide boots, coming up to the knee.”5

Because of their less defined class structure, westerners viewed slavery somewhat differently than did soldiers from Virginia and South Carolina. The Tennessee questionnaires concluded that before the war, in the words of one, “slaves and all worked together white and black.” There appears to have been a consensus among slaveholders and nonslaveholders that the institution was not a part of a social system that affected only the wealthier classes. Slavery existed within geographical pockets, and in those areas, according to several respondents, almost every family owned at least a few slaves. No letters or diaries gave the preservation of the institution as a motivation for enlisting. Westerners were much more likely to mention protection of their homes and social enthusiasm as reasons for joining.6

One historian has done a study of Yankee soldiers of the West who served in Sherman’s March to the Sea. Although they exhibited a wide range of views on the subject of black contraband, the Federals were unquestionably more intrigued with blacks than were western Rebels. Perhaps reflective of their nonentity status, blacks were rarely mentioned in the communications of the latter. When they were discussed, it was usually in a paternalistic tone, portraying them as children. Wrote S. R. Simpson of the Thirtieth Tennessee on June 17, 1864: “The niggers are enjoying themselves finely dancing round big log fires and playing their home made flutes.” Western Rebels, like Southerners generally, had little interaction with blacks. Those encountered within the context of army life were usually personal body servants or cooks, who adopted, if less than genuinely, the attitudes of whites. “Our Reg’t. has had 60 negroes with it all through the war & none has run away. They have been taught to despise the Yankees and do so. You can’t make one of our black boys madder than by calling him a ‘fool abolitionist,’” remarked a Texas Ranger.7

Very few men in the ranks ever knew of Major General Cleburne’s 1864 proposal to enlist slaves in the Confederate army. Captain Thomas Key was one who did; he was told by Cleburne himself. “The idea of abolishing the institution at first startles everyone, but every person with whom I have conversed readily concurs that liberty and peace are paramount questions and is willing to sacrifice everything to obtain them. All, however, believe the institution a wise one and sanctioned by God,” he wrote. Even if there was a consensus, as Key claimed, it appears to have been more an acceptance of the end of slavery than an embracing of the arming of blacks.8

The intense racism that festered just beneath the surface emerged late in the war, when westerners encountered black soldiers. The first such instance was during the 1864 Tennessee Campaign, when the Union garrison at Dalton, Georgia, was captured. “Some of the soldiers were very anxious to kill them [black troops]. But as they surrendered without fighting the men were not allowed to kill none only those who attempted to get away were shot by guards. The negroes had to obey the orders of the guards very strictly or they were shot immediately,” related a Georgian. When black troops were encountered during the Battle of Nashville, the Confederates reportedly went into a frenzy, yelling, “no quarter—to niggers.” Those Rebels captured by blacks acted as though they had been particularly disgraced.9

It is impossible to determine the extent of illiteracy in the Army of Tennessee, but a brief though illuminating piece in an Atlanta newspaper suggests that it may not have been as great as popularly believed. The article revealed that the soldiers mailed 502,114 letters at the Army of Tennessee Post Office in the quarter ending June 30, 1864. This number averaged to a surprising 5,517 letters a day during a time when two out of three months were spent in active combat. Surviving letters, however, are clear evidence that semi-illiteracy, especially among privates and noncommissioned officers, was widespread.10

Although a rough image represented the norm for westerners, this view is one-sided, for the Army of Tennessee cannot be fully understood without examining its components. As the Tennessee-Arkansas core of regiments was expanded to include Brigadier General Daniel Ruggles’s Louisiana regiments, Bragg’s corps from the Gulf, and two South Carolina regiments from the Atlantic coast, a dimension of sophistication and discipline was added that has often been overlooked. The Crescent Regiment of New Orleans, known as the Kid Glove regiment, was made up of bluebloods aged eighteen to thirty-five, some of whom brought their servants with them. Many parents, wives, and children followed the regiment to the railroad station in elegant carriages. Other outfits, such as the Orleans Guard Battalion and the Washington Artillery (Fifth Company) of New Orleans and the Twenty-first Alabama of Mobile, represented the flower of Southern society. Many of these outfits ended up in Jones Withers’s division after the Shiloh reorganization. According to Brigadier General Manigault, it proved to be the exceptional division in an army that was otherwise lacking in order and discipline, and it exhibited a “complete absence of martial appearance amongst the troops.”11

In early February 1862 Private Reuben McMichael of the Seventeenth Louisiana posed for the photographer at Camp Benjamin, Louisiana. He wrote his sister: “Sis, I sent you my ambrotype two or three days ago as you wrote me to send it to you. I don’t believe that you will think it is my picture for I am so fat and ugly.” Two months later, on April 6, 1862, McMichael was killed at Shiloh. (Gregg D. Gibbs Collection, Confederate Calendar Works, Austin, Tex.)

Unfortunately, the cultural differences between westerners and Gulf coast soldiers resulted in some friction. One of the more refined soldiers from New Orleans was frankly disgusted with the bulk of A. S. Johnston’s army, considering them “unprincipled and very degraded men and officers.” P. W. Watson, a member of the Forty-fifth Alabama (a midstate regiment), reciprocated. He noticed that several of the Louisiana regiments “are all dutch and irish & frinch the maddest people in the wirld I think tha stand mo [more] than we can tha have bin raised hard not a hardly anuf to eate in their lives the most of them are from new orleanes.” Captain Robert Kennedy of the First Louisiana, a New Orleans regiment, admitted that on the retreat from Kentucky in the fall of 1862, his men suffered from lice as badly as other regiments. Yet they refused to strip their shirts and delouse on the march—”they [Louisianians] prefer to stand the biting than acknowledge they were lousy like the ‘Yahoos.’” As late as January 1863 a meshing of troops had still not occurred, according to J. Morgan Smith of the Thirty-second Alabama, an outfit organized at Mobile. He openly confessed: “I hate the state [Tennessee], the institutions and the people and really feel as if I am fighting for the Yankee side when I raise my arm in defense of Tennessee soil.” He also claimed that there was “an alienation between the troops of the Gulf and the Border States that may grow into something serious.”12

Thus there was some intra-army conflict. There were differences between soldiers from, say, Mobile and the hill country of north Alabama and those from Memphis and east Tennessee. Still, if homogeneity is defined by states and nationality, the Army of Tennessee was much more analogous than was the Army of Northern Virginia. Approximately 75 percent of the regiments came from four states—Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. The Kentucky brigade had the lowest percentage of foreigners in the Confederacy—one-third of 1 percent. What aliens were present in the army were almost exclusively of one nationality—Irish.13

The army did not totally lack a cosmopolitan flavor. There were four regiments of ethnics—the Second Tennessee of Memphis, Tenth Tennessee of Nashville, Thirteenth Louisiana of New Orleans, and Twentieth Louisiana. The Second and Tenth Tennessee, both claiming the sobriquet “the Irish Regiment,” were the Army of Tennessee’s counterparts to the Sixty-ninth New York of the Army of the Potomac. Made up of 750 Catholics from the “Pinch” district of Memphis, the Second was known for its fighting prowess—and not just with the Yankees. It was said that the regimental chaplain, a Father Daly, served mass in the afternoon and settled drunken brawls at night. The regiment served appropriately in Pat Cleburne’s division. Six companies of the Thirteenth Louisiana were originally called the Avengo Zouaves and included French, Spaniards, Germans, Italians, Chinese, and Irish. A lieutenant who was assigned to this “international” battalion was shocked to discover that, in addition to their colorful baggy uniforms, almost every member had a black eye, broken nose, or bandaged head. The Twentieth Louisiana had six companies of Irish and four of Germans.14

There was a pervasive prejudice against such foreigners. When the Thirteenth Louisiana camped next to his regiment at Corinth, Robert Patrick described them as “a hard looking set composed of Irish, Dutch, Negroes, Spaniards, Mexicans and Italians with few or no Americans, and it is the same with all the regiments collected in or about our towns and cities.” Likewise, when several men from his regiment deserted one evening while at Corinth, Thomas Butler concluded: “Except the disgrace to the Regt. I do not care much about their going for they were Dutchmen and Yankees and were of very little use to us.” After Shiloh, the Spanish and French Guards, Companies G and K of the Twenty-first Alabama of Mobile, were transferred to another regiment. “I am glad of it—they were more trouble than all the rest of the regiment put together, and not worth a continental shin-plaster for any duty or a fight—In the battle of Shiloh they discharged their guns away up in the trees—with perfect safety to the Yankees,” testified a lieutenant in the regiment.15

Private John Rulle, a member of the Second Tennessee, was wounded at Shiloh and later killed at Chattanooga. (Herb Peck)

The soldiers of the West were largely apolitical. On three occasions President Jefferson Davis visited the Army of Tennessee, and the comments evoked were those of spectators viewing a celebrity. An Alabama soldier at Murfreesboro declared, “we had a jenral revew yesterday and we wer revewed by our prezedent Jef Davis he is a good looken man.” Reuben Searcy was thrilled that D...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Army of Tennessee Will Decide the Fate of the Confederacy

- Chapter 1: Certainly a Rough Looking Set

- Chapter 2: We Drill Seven Hours a Day

- Chapter 3: We Have Drew the Finest Arms

- Chapter 4: I Am Hearty as a Pig on Half Rations

- Chapter 5: The Aire Is a Right Smart of Sickness

- Chapter 6: I Will Have My Fun

- Chapter 7: I Saw 14 Men Tied to Postes and Shot

- Chapter 8: The Army of Tennessee Is the Army of the Lord

- Chapter 9: We Are Dissatisfied and We Don’t Care Who Knows It

- Chapter 10: I Never Saw Braver Men

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index