eBook - ePub

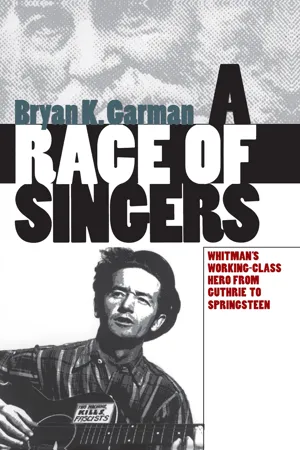

A Race of Singers

Whitman's Working-Class Hero from Guthrie to Springsteen

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

When Walt Whitman published Leaves of Grass in 1855, he dreamed of inspiring a “race of singers” who would celebrate the working class and realize the promise of American democracy. By examining how singers such as Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, and Bruce Springsteen both embraced and reconfigured Whitman’s vision, Bryan Garman shows that Whitman succeeded. In doing so, Garman celebrates the triumphs yet also exposes the limitations of Whitman’s legacy.

While Whitman’s verse propounded notions of sexual freedom and renounced the competitiveness of capitalism, it also safeguarded the interests of the white workingman, often at the expense of women and people of color. Garman describes how each of Whitman’s successors adopted the mantle of the working-class hero while adapting the role to his own generation’s concerns: Guthrie condemned racism in the 1930s, Dylan addressed race and war in the 1960s, and Springsteen explored sexism, racism, and homophobia in the 1980s and 1990s.

But as Garman points out, even the Boss, like his forebears, tends to represent solidarity in terms of white male bonding and homosocial allegiance. We can hear America singing in the voices of these artists, Garman says, but it is still the song of a white, male America.

While Whitman’s verse propounded notions of sexual freedom and renounced the competitiveness of capitalism, it also safeguarded the interests of the white workingman, often at the expense of women and people of color. Garman describes how each of Whitman’s successors adopted the mantle of the working-class hero while adapting the role to his own generation’s concerns: Guthrie condemned racism in the 1930s, Dylan addressed race and war in the 1960s, and Springsteen explored sexism, racism, and homophobia in the 1980s and 1990s.

But as Garman points out, even the Boss, like his forebears, tends to represent solidarity in terms of white male bonding and homosocial allegiance. We can hear America singing in the voices of these artists, Garman says, but it is still the song of a white, male America.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Race of Singers by Bryan K. Garman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I PROGRAMS OF CULTURE

1FOR THE WORKINGMAN’S SAKE

Imagining a Working-Class Hero

In the five years that preceded the publication of Leaves of Grass, Whitman befriended a group of artists and painters who, in 1851, invited him to address the Brooklyn Art Union. Although his speech indicated that the Carlylean connections between art, heroism, and morality weighed heavily on his mind, Whitman expressed a crankiness with the people that did not appear in his poetry. The poet idealized his fellow citizens, but the orator characterized them as money-grubbing philistines. He defined Americans as “a race to whom matter of fact is everything, and the ideal nothing,” as people who viewed “most things with an eye to pecuniary profit.” The artist, however, had the ability to cure this materialism. He could “go forth into the world and preach the gospel of beauty,” could recite a “heroic verse” that would reveal a universal moral code. Like Carlyle, Whitman defined the artist as hero: “I think of few heroic actions which cannot be traced to the artistical impulse. He who does great deeds, does them from his sensitiveness to moral beauty. Such men are not merely artists, they are artistic material. Washington in some great crisis, Lawrence in the bloody deck of the Chesapeake, Mary Stewart at the block. … All great rebels are innovators. … A sublime moral beauty … may almost be said to emanate from them. The painter, the sculptor, the poet express poetic beauty in description; for description is their trade, and they have learned it. But the others are heroic beauty, the best beloved of art.”1 Like the leaders Whitman enumerated, a successful artist had the potential to shape the history and character of the nation. In fact, both art and artist could serve a political function that went beyond the holding of public office. The “true Artist” could demonstrate that even the most horrifying despot has “never been able to put down the unquenchable thirst of man for his rights.”2

Three years after he published Leaves of Grass, Whitman continued to find moral and artistic inspiration in song. “A taste for music,” he observed, “when widely distributed among a people, is one of the surest indications of their moral purity, amiability, and refinement. It promotes a sociality, represses the grosser manifestations of the passions, and substitutes in their place all that is beautiful and artistic.”3 An ardent fan of opera, the abolitionist Hutchinson Family Singers, and the minstrel show, Whitman was profoundly influenced by antebellum musical forms. By examining his songs under a “moral microscope,” an instrument he used to scrutinize the national conscience in Democratic Vistas, we can begin to discern a morality that members of the race of singers he propagated have been eager to tease from his work.4 The fabric from which Whitman’s values were cut was artisan republicanism, an ideology without which his poetic and political tapestries would have certainly unraveled. To be sure, when the poet heard America singing, he listened to the “blithe and strong” voices of mechanics, masons, and carpenters who subscribed to a deeply conflicted but clear and consistent morality that enabled them to resist the acquisitive values of industrial capitalism.5 Time and again, Whitman reaffirms the ideals he learned as a carpenter’s son and printer’s apprentice, ideals that simultaneously expanded and contained his democratic vistas.

WHITMAN AND THE ARTISAN IDEAL

Built firmly on the American Revolution’s rhetoric of natural rights, artisan republicanism articulated ideas about freedom and equality that were inextricably bound to definitions of gender and race. This ideology belonged to skilled white northern craftsmen who, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, served apprenticeships, worked stints as journeymen, and aspired to owning their own shops. These mechanics derived their highly prized economic independence and their sense of manhood from their skills, providing valuable services to the community in exchange for reasonable compensation.

Most artisans did not expect, and in many cases did not desire, to live extravagantly. They sought a “competence” that would enable them to support their families single-handedly but were otherwise wary of wealth. Tight-fisted journeymen were decidedly unpopular with their peers. Men participated in a mutualistic leisure culture characterized by their eagerness to buy drinks for fellow craftsmen at local pubs and formed associations that required them to assist unemployed members of their trades.6 Wealth, they insisted, concentrated power in too few hands and imperiled the self-evident truths of freedom and equality. Consequently, they viewed greed as an immoral, unrepublican quality that threatened the health of the nation as well as their own freedom and independent manhood. The economic activities of manufacture and commerce were, like all others, subject to the moral laws of religion, and anyone who violated the principles of fair exchange committed a despicable act.7 Put simply, artisans were determined to prevent the unfettered pursuit of self-interest from making a mockery of the Republic. They held their manly independence sacred but recognized that if they were to maintain what they believed was a state of equality, they must sometimes subordinate their own interests to those of the community.8

This idealized equilibrium was disturbed, however, by the economic transformations that beset the workshops between 1810 and 1850. As improved modes of transportation opened regional and foreign markets, a number of enterprising artisans met the rising demand for their goods by implementing new technologies, dividing the labor process into component parts, sending work out to domestic laborers, and ultimately centralizing production under the factory roof. These developments altered the manufacturing process, but more important, they profoundly transformed the values that had characterized preindustrial economic exchange and labor relations. As entrepreneurs commodified labor, they separated it from customary communal and egalitarian values, which resulted in a social organization that was more individualistic and less democratic.9 Although an employer at the end of the eighteenth century had been obliged to feed and clothe his apprentice in addition to teaching him a trade, by the 1830s, he owed his employees nothing but a wage, and that too was becoming much less of a burden on the employer’s bankbook. As trades were deskilled and routinized, employers drew from a vast pool of unskilled immigrant labor and female outworkers, all of whom worked for far less than a journeyman’s competence. By 1850, the crafts were “bastardized,” and qualified journeymen had difficulty finding positions in which they could properly ply their trades.10

The New York City artisans with whom Whitman rubbed elbows did not relinquish their collective ethos easily, and they quickly banded together to protect their economic interests. In 1831, the General Trades Union, an amalgamation of tailors, shoemakers, carpenters, and printers like those to whom Whitman had apprenticed, brandished the labor theory of value to assail greedy employers who had, in the words of one artisan, “disturbed the natural order of things.”11 Raw materials, insisted these journeymen, acquired economic value only after skilled hands transformed them into finished goods, so it was the labor involved in the production of manufactures rather than in the distribution of them that created wealth. Industrialization turned the artisan’s conception of capitalism upside down. As entrepreneurs brokered finished goods, they accumulated tremendous wealth, whereas journeymen saw their standard of living fall dramatically. In an attempt to reassert control over the labor process and stabilize wages, workers organized in opposition to their former masters. But not all craftsmen resisted the temptation of wealth. By 1837, an entrepreneurial class of tradesmen emerged, causing artisan republicanism to bifurcate into two distinct strands: one that upheld skilled white male egalitarianism and collectivity and one that emphasized individual freedom and lent itself to unbridled capitalist development.12

Whitman consistently opposed labor unions, not because they pursued a more equitable wage but because he worried that their members “would set on their fellow-workingmen who didn’t belong to their ‘union’ like tigers or other beasts of prey.” Such compulsion, he opined, threatened the artisan concept of free and independent manhood.13 These reservations did not, however, prevent Whitman from railing against entrepreneurs who wrenched republicanism from its egalitarian moorings and used it to promote their own private gain. As early as 1840, he commented on the proliferation of wage labor when he urged the “rich man” to observe the “poor, miserable” workingman who rises “an hour before sunrise, fussing, and mussing, and toiling and wearying, as if there were no safety for his life, except in uninterrupted motion.”14 His disdain for the emerging industrial order reappeared in his editorials in the Brooklyn Eagle. Whitman found injustices in the treatment of workers in the city’s lead factories, where wages recently had been lowered. Angered by the stingy employers, he sarcastically announced that the “poor manufacturers will save the enormous sum of thirty-seven and one half dollars per week!” Such a paltry figure was “nothing to the rich manufacturers,” but to the “poor man,” Whitman recognized, it was quite a “serious matter.”15 Disturbed by an economic system that degraded the material and emotional lives of working people and endangered the nation’s democratic promise, Whitman condemned the “morbid appetite for money” that his fellow citizens had developed. The “mad passion for getting rich,” he explained, “engrosses all the thoughts and the time of men. It is the theme of all their wishes. It enters into their hearts and reigns paramount there. It pushes aside the holy precepts of religion, and violates the purity of justice. The unbridled desire for wealth breaks down the barriers of morality, and leads to a thousand deviations from those rules, the observance of which is necessary to the well-being of our people.”16 Artisans advocated private property and free markets, but when the pursuit of happiness endangered the public good and threatened the concept of justice, many workingmen, as well as Whitman, believed that the moral tenets of republicanism were compromised. If left unchecked, the “morbid appetite” would upset the tenuous balance between personal liberty and social equality.

As artisans formed craft guilds and labor unions to maintain this balance, they reinforced their solidarity by creating a largely homosocial, if not homoerotic, leisure culture. Through their membership in benevolent societies and fire departments, artisans proclaimed their commitment to the community. By sharing rooms in boardinghouses, engaging in wrestling bouts, and, strangely enough, squaring off in bare-knuckled prizefights, they expressed their affection for one another. Because New York City’s journeymen spent most of their time with other men and were deeply committed to protecting one another’s social and economic interests, it is not surprising that they established intimate relationships.17 In fact, as historian Elliot Gorn argues, they “focused so much emotional attention on one another” that they frequently described coworkers as “creatures of beauty.”18 This fascination with male bodies presented itself in a wide range of physical activities. Backslapping, hugging, kissing, and bed sharing were routine among same-sex friends in the nineteenth century, and because the concept of a distinct homosexual identity did not emerge until the turn of the century, men and women could participate in homosexual acts without fearing long-term repercussions.19 This is not to say that such behavior was widely sanctioned or that all, or even most, journeymen indulged in it. Nevertheless, the absence of homophobia and the anonymity of the industrial city allowed for a more fluid sexuality, and it is safe to aver that some workingmen acted on the homoerotic desire that charged their highly physical, masculinized culture. Whitman, who amplifies this impulse in “I Sing the Body Electric,” believed that this manly love was particularly prevalent “among the mechanic classes.”20 He celebrated a homoerotic adhesiveness that he found in

The wrestle of wrestlers . . two apprentice-boys, quite grown, lusty, goodnatured, nativeborn, out on the vacant lot at sundown after work,

The coats vests and caps thrown down . . the embrace of love and resistance.21

This culture nurtured a collectivist impulse in which individual freedom was firmly tethered to somewhat limited ideas about equality and social responsibility. Artisan society was not, however, as egalitarian as its members imagined. All crafts did not share equal standing in the community, and women, the unskilled, and people of color had little stake in the society’s politics. When black, immigrant, and female workers began to compete for craftsmen’s jobs between 1820 and 1850, racism and sexism hardened.22 As women outworkers and factory operatives displaced skilled men, their husbands and fathers viewed them as competitors rather than coworkers and redoubled their efforts to exclude them from the republic of labor. Even Whitman, who preached gender equality in his poetry, could not imagine a place for women in the artisan economy. For him, the ideal of the “noble female personality” was the “wife of the mechanic,” the “mother of two children, a woman of merely passable English education” who “beams sunshine out of all these duties”: “cooking, washing, child-nursing, house-tending.”23 The wife’s “independence” depended on her exclusion from the masculine public, where her husband had ample opportunities to strengthen his economic position.24

As workingmen clung to their masculinity amid the vicissitudes of industrialization, they also held steadfastly to the privileges accrued by their racial status. David Roediger argues that whiteness was a key component of the republican man’s identity and a physical quality from which he derived considerable social and psychological benefit. Concerned that their freedom and independence were being taken from them, that industrialization was creating white wage slavery, journeymen responded by defining themselves as freemen, a term that clearly distinguished them from black slaves.25 Further evidence of white working-class race consciousness appeared in the minstrel show, in which performers and their audiences constructed African Americans as both puerile and savage, and in the Free-Soil movement, w...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Be Radical—Be Not Too Damned Radical

- Part I. Programs of Culture

- Part II. Living Leaves of Grass

- Part III. Several Yarns, Tales, and Stories

- Part IV. Ghosts of History

- Encore: This Hard Land

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index