- 212 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frontiers of Risk Management, Volume II

About this book

Frontiers of Risk Management was developed as a text to look at how risk management would develop in the light of Basel II. With an objective of being 10 years ahead of its time, the contributors have actually had even greater foresight. What is clear is that risk management still faces the same challenges as it did ten years ago. With a series of experts considering financial services risk management in each of its key areas, this book enables the reader to appreciate a practitioners view of the challenges that are faced in practice identifying where appropriate suitable opportunities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Frontiers of Risk Management, Volume II by Dennis Cox in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Negocios y empresa & Finanzas. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Use of Credit Rating Agencies and Their Impact on the IRB Approach

Markus Krebsz, Gary van Vuuren, and Krishnan Ramadurai

Fitch Ratings

Introduction: The IRB Approach—Cornerstone of Basel II

This chapter was originally drafted when Basel II was new. Basel III in its various manifestations does not make any major change to Basel II in this regard. IFRS 9 requiring a general provision for any facility to be introduced essentially builds upon the IRB framework discussed in this chapter which remains as valid today as it was when originally drafted.

The IRB approach is a cornerstone in the Basel II capital framework and a critical innovation in the regulatory capital treatment of credit risk. Indeed, much of the work of the Committee since June 1999 has focused on building and refining the IRB framework, including the form and calibration of the capital formulas, the operational standards and risk management practices that qualifying banks must follow, and the treatment of different types of assets and business activities. While this represents a new path in banking regulation, however, the concepts and elements underlying the IRB approach are based largely on the credit risk measurement techniques that are used increasingly by larger, more sophisticated banks in their economic models. The IRB approach is, at heart, a credit risk model—but one that is designed by regulators to meet their prudential objectives.

The building blocks of the IRB capital requirements are the statistical measures of an individual asset that reflect its credit risk, including:

- probability of default (PD), or the likelihood that the borrower defaults over a specified time horizon;

- loss given default (LGD), or the amount of losses the bank expects to incur on each defaulted asset;

- remaining maturity (M), given that an instrument with a longer tenor has a greater likelihood of experiencing an adverse credit event; and

- exposure at default (EAD), which, for example, reflects the forecast amount that a borrower will draw on a commitment or other type of credit facility.

Under the most sophisticated or advanced version of the IRB approach, banks are permitted to calculate their capital requirements using their own internal estimates of these variables (PD, LGD, M, and EAD), derived from both historical data and specific information about each asset. More specifically, these internal bank estimates are converted or translated into a capital charge for each asset through a predetermined supervisory formula. Essentially, banks provide the inputs and Basel II provides the mathematics.

As a credit risk model, the IRB formula has been designed to generate the minimum amount of capital that, in the minds of regulators, is needed to cover the economic losses for a portfolio of assets. Therefore, the amount of required capital is based on a statistical distribution of potential losses for a credit portfolio and is measured over a given period and within a specified confidence level. The IRB formula is calculated based on a 99.9 percent confidence level and a one-year horizon, which essentially means that there is a 99.9 percent probability that the minimum amount of regulatory capital held by the bank will cover its economic losses over the next year. In other words, there is a one in 1,000 chance that the bank’s losses would wipe out its capital base, if equal to the regulatory minimum.

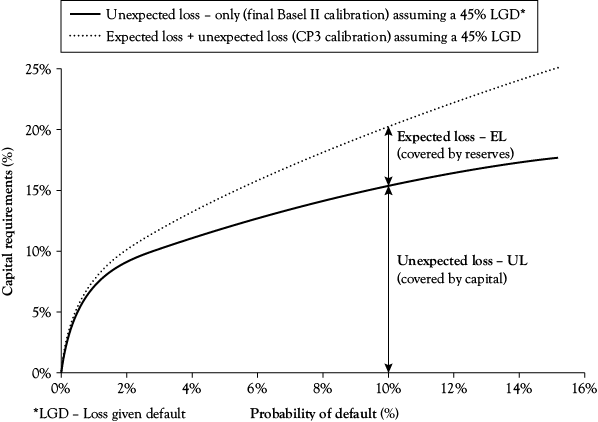

The economic losses covered by the final IRB capital charges represent the bank’s UL (unexpected losses), as distinguished from losses that the bank can reasonably anticipate will occur, or EL (expected losses). Banks that are able to estimate EL typically cover this exposure through either reserves or pricing. In statistical terms, the EL is represented by the amount of loss equal to the mean of the distribution, while UL is the difference between this mean loss and the potential loss represented by the assumed confidence interval of 99.9 percent. As seen in Exhibit 1.1, the credit risk on an asset, reflected both in the UL and the EL, increases as the default probability increases. Likewise, the level of credit risk also increases with higher loss severities, longer maturities, and larger exposures at default.

Exhibit 1.1 Corporates

Source: Fitch Ratings.

In addition (see Exhibit 1.1), EL contributes a relatively small proportion of the capital charge for high-quality (or low-PD) borrowers, but an increasingly greater proportion as the borrowers move down the credit quality spectrum. For example, for a loan to a very strong (or low-PD) borrower, the bank anticipates that the asset will perform well and is unlikely to experience credit-related problems. Therefore, any severe credit deterioration or loss that might occur on the loan to the borrower would differ from the bank’s expectation and, thus, be explained primarily by UL. By contrast, for a loan to a weaker (or high-PD) borrower, the probability of some credit loss is much greater, enabling the bank to build this expectation of loss into its pricing and reserving strategies. Therefore, at the lower end of the credit quality spectrum, EL is a larger component of the credit risk facing the bank than at the higher end of the quality spectrum.

Of course, the amount of economic loss that an asset might incur depends on the type or structure of the asset. For example, is the exposure to a major corporation or to an individual borrower? Is it secured by collateral? How does the borrower generate funds for repaying the bank? What is the typical life or tenor of the asset? How is its value affected by market downturns? Different credit products can behave quite differently, given, for example, their contractual features, cash-flow patterns, and sensitivity to economic conditions. Basel II recognizes the importance of product type in explaining an asset’s credit profile and provides a unique regulatory capital formula for each of the major asset classes including corporates, banks, commercial real estate (CRE), and retail.

Critical Elements of IRB

A critical element of the IRB framework and a key driver of the capital charges are the assumptions around correlation and the correlation values used in the formulas. Basel II does not recognize full credit risk modeling and does not permit banks to generate their own internal estimates of correlation in light of both the technical challenges involved in reliably deriving and validating these estimates for specific asset classes and the desire for tractability.

In generating a portfolio view of the amount of capital needed to cover a bank’s credit risk, Basel II captures correlation through a single, systematic risk factor. More specifically, the IRB framework is based on an asymptotic, single-risk factor model, with the assumption that changes in asset values are all correlated with changes in a single, systematic risk factor. While not defined under Basel II, this systematic risk factor could represent general economic conditions or other financial market forces that broadly affect the performance of all companies.

In summary, a low correlation implies that borrowers largely experience credit problems independently of each other due to unique problems faced by particular borrowers. On the other hand, higher asset correlations indicate that credit difficulties occur simultaneously among borrowers in response to a systematic risk factor, such as general economic conditions.

Correlation Assumptions

Under Basel II, the degree to which an asset is correlated to broader market events depends, in certain cases, on the underlying credit quality of the borrower. Based on an empirical study conducted by the Committee, the performance of higher-quality assets tends to be more sensitive to—and more correlated with—market events. Although this finding might at first seem counterintuitive, it is consistent with financial theory that states that a larger proportion of economic loss on high-quality exposures is driven by systematic risk. By contrast, the economic loss on lower-quality exposures is driven mainly by idiosyncratic, or company-specific, factors and relatively less so by systematic risk. This reasoning suggests that the performance of lower-quality assets tends to be less correlated with market events and, therefore, the biggest driver of credit risk is the high-PD value of the borrower or, more broadly, the lower intrinsic credit quality of the borrower.

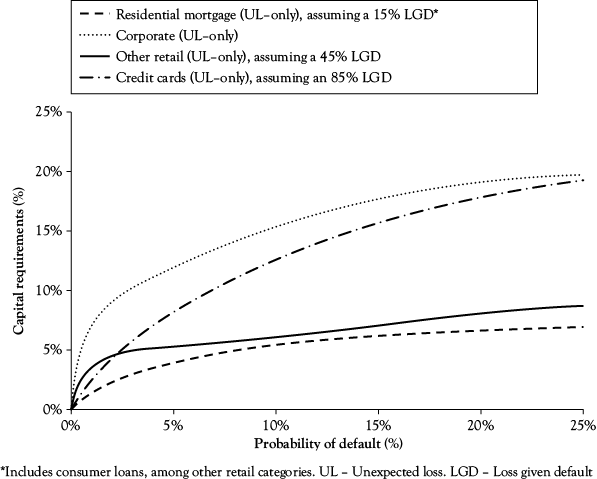

The IRB approach distinguishes between three types of retail assets—credit cards (known formally as qualifying revolving retail exposures [QRRE]), residential mortgages, and consumer lending (classified under other retail). Basel II has calibrated the three retail capital curves to reflect the unique loss attributes of each of these different products, as seen in Exhibit 1.2. The IRB formulas for the three retail product types are identical except for the underlying correlation assumption, a key driver of the shape and structure of the capital requirements. Additionally, the Basel II charges are sensitive to the underlying LGD estimate, which in practice can vary substantially across the different types of retail assets. For example, loss severities tend to be much higher for credit card assets than for residential mortgage lending.

Exhibit 1.2 Retail

Source: Fitch Ratings.

The decision, first announced in July 2002, to treat credit cards as a separate asset class under Basel II was an important step in recognizing the typically lower-risk profile of general-purpose credit cards, particularly to prime borrowers. Since that decision, the Committee has continued to refine its treatment of credit cards to reflect the unique loss attributes of this asset class.

The move under Basel II to a UL-only capital charge implicitly acknowledges the sophistication and reliability of banks to measure and manage their EL exposure. For retail products—and credit cards in particular—the development of sophisticated risk measurement models has enabled many banks to estimate EL and incorporate it into risk-based pricing and reserving practices. For banks with less sophisticated internal models, the discipline of preparing for the IRB approach will help them to develop more refined EL-based pricing and reserving. The move to a UL-only framework included eliminating future margin income (FMI) from the capital calculations. Fitch supports this change, having previously expressed concern over the inclusion of FMI as an offset to regulatory capital charges. The recognition of FMI would have unnecessarily clouded the regulatory capital base as, in our view, the loss absorption of FMI is not sufficiently reliable to warrant treatment as capital. As FMI is a statistical generation of potential future income ability that fluctuates with interest rates, as well as the economic cycle, FMI could be affected by market dynamics. Competitive pricing could also negatively affect the ability of banks to fully realize their estimates of FMI. Fitch takes a conservative view of FMI within the credit-rating process, allowing no capital recognition in rating financial institutions and permitting limited recognition in rating certain more junior classes of credit card, asset-backed securities (ABS).

Another critical change to the Basel II framework and a flashpoint for the industry has been the level of the correlation estimate used in the IRB formula for credit cards. More specifically, Basel II applies a fixed 4 percent correlation across all PD levels, rather than calibrating correlation as a function of borrower quality (correlation was previously set to range from 11 percent for high-quality borrowers to 2 percent for low-quality borrowers). The intuition behind the previous treatment of setting the correlation higher for high-quality (or low-PD) assets than for low-quality (or high-PD) assets was the assumption that a larger proportion of the economic risk on high-quality exposures is driven by systematic (as opposed to idiosyncratic or borrower-specific) risk factors. While this conceptual reasoning is sound, the higher correlations applied to assets at the lower PD levels appeared to result in fairly onerous capital charges on these assets, at least according to industry estimates.

While correlation could theoretically vary within a credit score band, the adoption of the 4 percent correlation factor is significantly lower than the 11 percent peak and results in lower capital charges on high-quality credit card assets. For example, as illustrated in Exhibit 1.3, a pool of credit cards with a PD of 2 percent and an assumed LGD of 85 percent would have required regulatory capital of 5.5 percent based on the ranging correlation of 11 percent–2 percent (assuming a UL-only calibration). Using instead the fixed correlation of 4 percent, the regulatory capital requirements on this same pool would decline to about 4.5 percent, or a 100 basis-point reduction in the charge at the 2 percent PD level. The fixed 4 percent correlation only prov...

Table of contents

- Cover

- halftitle

- title

- copyright

- abstract

- contents

- 01_Chapter 1

- part1

- 02_Chapter 2

- 03_Chapter 3

- 04_Chapter 4

- 05_Chapter 5

- 06_Chapter 6

- part 2

- 07_Chapter 7

- 08_Chapter 8

- 09_Chapter 9

- 10_Chapter 10

- 11_Chapter 11

- 12_Bibliography

- 13_Index

- 14_Adpage