![]()

1 Design

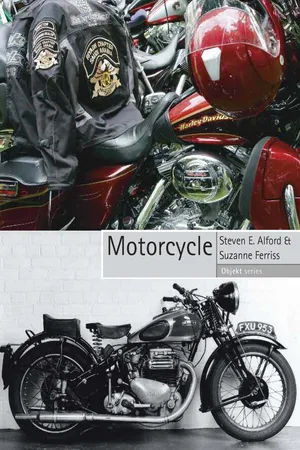

The dream of every design engineer is to come up with the most beautiful sports motorcycle in the world then turn it into the fastest, most exclusive, sought after and powerful on the market. This was my dream too. I wanted to feel the reactions of a racing bike that could put every available ounce of power through to the ground beneath me and feel it lean into and hug the curves. I wanted to see perfection in every single detail of material, shape and efficiency, an example of mechanical elegance that would be immortal. I wanted a motorcycle with no half measures, a motorcycle that would combine all of the technology tried out over years of research, a motorcycle intended for connoisseurs and true lovers of motorcycles. All of this was my dream. Today it has come true.

Massimo Tamburini

The 2005 MV Agusta F4 Tamburini is an in-line, four-cylinder, six-speed, chain-driven motorcycle that can travel from 0 to 60 mph in 3.47 seconds, with a top speed of 190 mph. The entire bodywork is carbon fibre, including the intake ducts. The overall design reflects Massimo Tamburini’s original masterwork, the Ducati 916. This bike, of which only 300 were made, retailed at $42,695. It sold out.1

Founded in 1992, Chongqing’s Lifan Industry (Group) Co., Ltd is the largest motorcycle manufacturer in China. (In 2005 China produced over 17 million motorcycles.)2 Employing over 8,700 people, Lifan makes motorcycles sold in over 100 countries including Southeast Asia (including Japan), Europe, Africa and South America, with plant operations in 28 countries. Lifan produces, among other products, the LF50QT-15. Weighing in at 148 lb, with 48ccs, this single cylinder four-stroke can reach speeds upward of 30 mph.3

Lifan LF50QT-15, 2005.

Which is the real motorcycle, the MV Agusta or the 50cc Lifan? Before we can even begin to answer that question we have to ask, what is a motorcycle?

MV Agusta F4 Tamburini, 2005.

The Bike

Before the motorcycle came the bicycle. Its forward, propulsive movement results from the transfer of energy from a person’s legs to the wheel (originally the front, most often the rear), rather than a motor. The first attempts at bicycle design, however, lacked any means of self-propulsion, requiring instead that the rider push himself and the device forward, using his feet to push off from the ground, first walking then running.4 Comte Mede de Sirvac’s 1791 invention was little more than a wooden bar ending in two forks that held two carriage wheels. Baptized the cheval de bois (wooden horse), it inspired a host of more decorative imitations, first called célérifères (from the Latin fero, meaning to carry, and celer, fast) then vélocifères after the Revolution.5 None, however, had any means of steering. In 1817 Karl Friedrich von Drais, a forester and inventor from Mannheim, Germany, devised the first steerable bicycle-like device: he fixed the front wheel to a vertical shaft, allowing the rider to turn left or right, and added a stomach rest to help the rider in propelling the device (which was, like de Sirvac’s, made of walnut wood). Conceived primarily as an aid to running, Drais’ device enabled its operator to reach the heady speed of 5 to 6 miles an hour, about twice normal walking speed.6 Called the ‘Draisine’, it was patented on 5 January 1818 in Baden, and devices modelled on its design became more generally known as velocipedes (from velox pedis, swift of foot). But they, too, lacked any means of independent forward propulsion.

A pair of Frenchmen took the next step, giving the rider a means to self-propel the velocipede. In 1861 the father and son French team of Pierre and Ernest Michaux produced what would become the bicycle, a device whereby the rider could employ his or her feet on the front wheel to move forward. In 1855 they had tried fitting a lever to the wheel, to be powered by the arms, but the design failed owing to balance problems and structural weakness. Then they attached two connecting rods to the front wheel and fastened two large nails (later replaced by a piece of bent tube) to form a foot rest, creating the first pedal. Later models of the ‘michaudine’ also featured an iron pad to supply friction on the back wheel, the first brake. So successful was their design that they established the first real bicycle industry, ‘Michaux et Co.’ (later Compagnie Parisienne). Even though these early bikes were soon used for racing, they were still bulky, rigid and heavy, capable of 8 mph at most.

Karl Friedrich Drais’ ‘Draisine’, 1817.

After 1865 the race was on to make the device faster. Englishman James Starley of the Coventry Company made a series of modifications to improve the original velocipede, making it lighter, more durable and more mechanically efficient. In 1879 the ungainly velocipede gave way to a model designed by Harry Lawson, featuring a chain linking pedals to the rear wheel. In the first half of the 1880s, frames adopted a so-called cross shape: a tube ran from the saddle to the pedal wheel and intersected half-way down with another tube connecting the rear wheel to the handlebars. It was elegant and slender but not sufficiently strong or rigid. Englishman Thomas Humber unveiled a diamond-pattern frame at the International Velocipede Exhibition in London in 1866, known as the ‘safety’ frame because it guaranteed improved stability to the rider. This design was further refined by James Starley’s nephew, John Kemp Starley, to produce the Rover Safety bike in 1885. The stability of the safety bike’s rigid frame relied on its diamond shape – two triangles connected on what would be the hypotenuse (although it lacked the downtube under the seat seen in modern bicycles). The reliability of this frame relied in turn on the industrial means to produce light, strong metals in a tubular shape.

Sophisticated metallurgical techniques were also required to produce a sturdy but flexible chain that would connect the pedals to the rear wheel, transferring leg power to the rear wheel with sufficient strength to overcome the forces of inertia and friction. Chains were first proposed by Leonardo da Vinci in 1482 and, by the end of the eighteenth century, chains modelled on the pin-and-plate design were employed by mechanical engineers. In 1880 Hans Renold, a Swiss inventor and engineer transplanted in 1873 to England, developed the bush roller chain, a tremendous improvement on the pin-and-plate design. Essentially, the bush roller chain has cylindrical ‘rollers’ mounted on bushings between inner and outer plates, permitting smooth and reliable weight distribution and movement of the chain around a cog wheel.

Finally, designers had to overcome complaints about the ‘bone shaking’ experience of riding, devising means of shock absorption for the wheels. While rubber was a natural substance for the outer surface of wheels, the road to usable rubber was a long one. After decades of hapless research, in 1839 Charles Goodyear discovered vulcanization, which combined rubber with chemical substances to make it elastic. Most bicycle manufacturers relied on rubberized strips of cloth nailed to the wheels. However, in 1888, three years after the production of the Rover Safety Bicycle, John Dunlop produced the first pneumatic (air-filled) tyres that could be used for a bicycle. Others contributed to tyre technology, including Giovanni Battista Pirelli (1892), André Michelin (1895), Philip Strauss (1911) and Frank Seiberling (1908). Through the efforts of the Starleys, Renold and Dunlop, we have all the necessary conditions (except for an engine) for the development of the motorcycle.

The diamond-shaped frame provided a natural area to affix a motor – either to the upper transverse bar or, in models subsequent to the Rover, the downtube beneath the seat. Over time, though, motors have been affixed to the rear axle (scooters) and the front wheel as well. The optimum positioning of the engine relies on a number of factors (balance, transfer of power from the engine, relation to other components, etc.), but most designers have placed the engine just ahead of the seated rider and behind the steering column.

Once it occurred to the mechanically inclined to mount a motor onto a bicycle, the question of the identity of the resulting devices remains. For example, Briton Edward Butler mounted a gasoline engine to a vehicle in 1884. However, it had two front wheels and one rear wheel. Car? Motorcycle? Tricycle? Although a gasoline engine propels the vehicle forward, Butler’s vehicle is neither an automobile nor a motorcycle. (Sidecar aficionados will note that their motorcycle also has three wheels, further complicating the issue.) In the US Sylvester Howard Roper developed a motorcycle in 1867 (some claim 1869) which, however, was powered by steam, followed in 1868 by Frenchman Louis Guillaume’s patented steam engine mounted on a bicycle built by Pierre and Ernest Michaux. Is the source of energy that powers the engine a relevant consideration?

Designing and positioning the engine

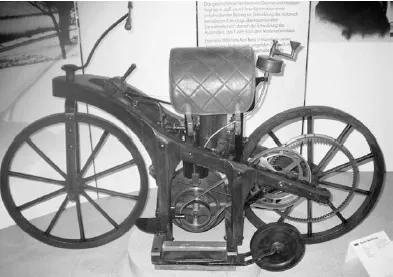

Despite the difficulty of defining what we mean by the term ‘motorcycle’, for many historians German engineers Nicholas August Otto and Gottlieb Daimler share the laurels for creating the first motorcycle. Otto, Daimler’s boss, created the engine in 1876, and in 1885 Daimler took this gasoline-powered, four-stroke engine and created the Daimler Einspur, something resembling a torture device with training wheels, named, for reasons obvious to anyone who rode it, the ‘Bone Crusher’ (the term perhaps a variation on the name for early bicycles, ‘bone shakers’). The original flight of the Bone Crusher took place on 10 November in Canstatt, near Stuttgart. Ironically, Daimler never rode his creation – his interest was in testing the engine, not creating a vehicle – leaving that to his colleague Wilhelm Maybach. Daimler himself was no motorcycle enthusiast, seeing the motorcycle as a mere precursor to the more stable, sedate automobile.7

Daimler Einspur, 1885.

A subsequent important development in engine technology came in France, where in 1894 Comte Albert de Dion and Georges Bouton, originally purveyors of steam engines, designed a tricycle with a 125cc engine that, licensed in various European countries and America (and appropriated by many non-licensees), became the standard for motorcycle engines.

The mechanics of internal combustion engines are complicated and, in their details, frequently changing. In early motorcycle design, three elements of engine design are worth noting: ignition, carburation and lubrication.

To achieve the rotational force necessary to propel the motorcycle forward, the engine’s piston(s) need to be propelled upward and downward inside the cylinder through a controlled explosion. Depending on the placement of the engine various means can transfer that force to the wheel, causing the motorcycle to move forward. To make the engine crank, one needs a substance that explodes – most commonly a mixture of air and petrol – and an ignition source to cause the explosion. In early engines both the mixing of the fuel–air mixture and igniting it were tricky and often dangerous.

Ignition designs went through three iterations: flame, hot tube and magneto ignition (the latter resulting in spark plug designs common today). In flame ignition, a portion of the cylinder was opened and literally exposed to an open flame, prompting the explosion. This method was obviously dangerous and difficult to control. In hot tube ignition, rather than exposing the fuel–air mixture directly to a flame, a flame heated a tube mounted on the cylinder head. The red hot tube then ignited the fuel–air mixture. Both these methods created problems with timing and, owing to their crudeness, shortened the life of the engine. A magneto system, common in almost all but diesel engines, allowed for a controlled spark that ignites the mixture. One of the reasons for the popularity of the de Dion-Bouton engine was the presence of a battery-and-coil ignition. As in the magneto system it used a spark to ignite the mixture, but it employs an external power source, the battery, rather than an internal flywheel magnet, to do so. (These parallel technologies lasted at least until the early 1960s.) However, even with this more advanced ignition system, care had to be taken to insulate the electrical charge, which could disperse across the metal engine block. Advances in rubber and ceramic insulation were necessary to perfect this technique. Another problem was that, as engine speed increases, the time between ignitions decreases. A solution to this problem was a manual adjustor that controlled the frequency of the sparking.

One factor determ...