![]()

ONE

Interdisciplinary Ripples across the Indian Ocean

KRISH SEETAH AND RICHARD B. ALLEN

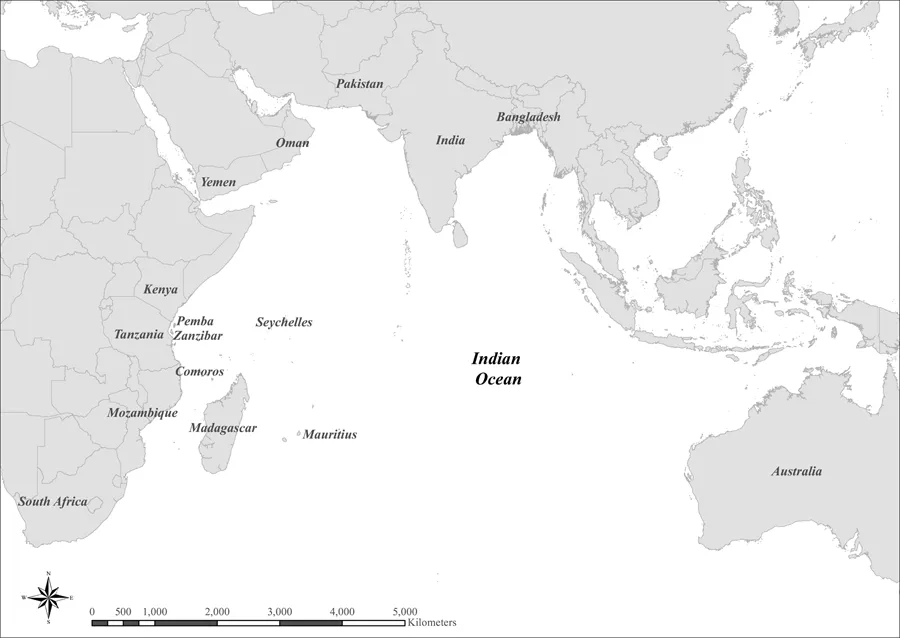

THE INDIAN OCEAN, LARGELY ignored by historians and social scientists until the 1980s,1 has become the focus of increasing interest to academics from disciplines as varied as anthropology, political science, and sociology. These scholars have been attracted by the social and cultural diversity of an oceanic world that encompasses southern and eastern Africa, the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, the Indian subcontinent, the Malay Peninsula, the Indonesian archipelago, and Australia (map 1.1). Evidence of this scholarly interest includes the organization of a growing number of international conferences on this oceanic world since 1979.2 The launching of journals dedicated to Indian Ocean studies in 1982, 1993, and, most recently, 2015;3 the establishment of an Indian Ocean World Centre at McGill University in Montréal in 2004; and vigorous discussion among historians about how the Indian Ocean world should be conceptualized further attest to this expanding scholarly interest.4 Of greater practical significance is the publication of ever-increasing numbers of articles, monographs, and edited collections that explore social, economic, cultural, and political life in this oceanic basin and seek to situate the Indian Ocean in the broader context of world history.5

Frequently missing from this burgeoning discourse, however, are contributions by archaeologists, and historical archaeologists in particular,6 as well as conscious attempts to study this region’s past from an interdisciplinary perspective. A recent special edition of the journal Slavery and Abolition demonstrates that some historians are increasingly aware of the potential insights that the study of material culture in archaeological contexts can provide,7 an awareness matched by a growing appreciation among some archaeologists of the value of “text-aided” archaeology.8 Despite such developments, concerted efforts to cultivate interdisciplinary approaches to individual research projects and, ultimately, to academic disciplines remain tangential at best.

This book seeks to begin the process of creating a more explicitly interdisciplinary approach to Indian Ocean studies by drawing on the expertise of the archaeologists, historians, artists, and anthropologists who participated in the workshop Connecting Continents: Case Studies from the Indian Ocean World held at Stanford University in March 2014. In addition to encouraging scholars to adopt interdisciplinary approaches to studying this region’s peoples, cultures, and history, the workshop sought to establish a research agenda for a part of the world that is just beginning to be a subject of serious historical archaeological interest. In so doing, the workshop’s participants set out to transcend the kind of disciplinary and subdisciplinary particularism that all too often plagues research agendas and programs, especially in parts of the world that have hitherto attracted limited scholarly interest.9

CONCEPTUALIZING CONNECTIONS

Such an undertaking requires an awareness of the problems that can easily complicate attempts, especially interdisciplinary ones, to reconstruct and analyze the complexities of the human experience in the Indian Ocean in greater detail. Historians of slavery, for example, have long appreciated the evidentiary and conceptual difficulties that hamper attempts to reconstruct slave trading in this oceanic basin. These problems include a paucity of archival sources, the pervasive Atlantic-centrism in modern slavery and African diaspora studies, and a penchant for geographical, chronological, and topical compartmentalization that often inhibits attempts to study human interaction from a comparative or panregional perspective.10 Archaeologists working in the Indian Ocean face similar problems, the most salient of which is the extent to which Atlantic-inspired models influence research in the Mare Indicum.11 While archaeologists working in the Indian Ocean obviously need to be aware of such conceptual frameworks, we must remember that the Indian Ocean and Atlantic worlds differed from one another in significant ways. Such differences are readily apparent whenever historians discuss the various free and forced labor trades and systems that have been major features of life in both of these oceanic worlds.12 Archaeologists need to be equally aware of such differences as they seek to understand the nature, dynamics, and impact of population movements within and between vast and diverse geographic regions.

MAP 1.1. The Indian Ocean, with locations discussed in the volume.

A particularly serious problem facing Indian Ocean archaeologists is the general lack of research on this part of the globe. Except for the Swahili Coast and South Africa, few sites in the Indian Ocean basin have been subject to the kind of careful excavation and analysis that can shed substantive new light on social, economic, and cultural connections within and across this region.13 A dearth of artifacts, artifact catalogues, and other basic forms of data has, in turn, precluded development of the kinds of typologies upon which archaeological analysis of material culture often rests. Other problems include nonexistent or poorly calibrated dating profiles for the region as a whole, particularly for historical but also for prehistorical periods, and minimal mapping of the crossregional movement of goods.14

Reconstructing the social, economic, cultural, and political connections that have existed for hundreds of years between the disparate regions and peoples of this oceanic basin invariably entails addressing multiple conceptual issues, perhaps foremost of which is, What do archaeologists understand by the notion of an Indian Ocean “world”? There can be little doubt that many historians readily subscribe to the notion, first popularized by Fernand Braudel’s classic work on the Mediterranean in the age of Philip II,15 that oceanic basins can be viewed as integrated “worlds” whose constituent parts are linked together in various ways, be they ecological, cultural, economic, or political. This concept’s popularity reflects the belief that because such worlds are distinct zones of biological, cultural, and economic interaction and integration, they allow large-scale historical processes to be seen in sharper relief.16 However, as recent discussions among historians about the nature of the Atlantic “world” attest, defining oceanic worlds largely in geographical terms can also impede a deeper understanding of the ways in which different regions have interacted with one another through time.17 Recent studies of the Dutch East India Company’s multinational labor force, the politics and ideology of the early British East India Company state, the geography of color lines in Madras and New York, identity and authority in eighteenth-century British frontier areas, British transoceanic humanitarian and moral reform programs, and European slave trading in the Indian Ocean indicate that these concerns are equally relevant to the Indian Ocean.18 Archaeologists should also be concerned about this concept’s limitations, especially since one of their discipline’s major strengths lies in its emphasis on studying interaction through time and across space.

Other problems reflect the differences between what historians and archaeologists do and how they do it (i.e., the scale of research, types of data collected, and questions asked and addressed). Historical research is usually heavily dependent on written documents, although other sources, such as oral tradition, may also help in reconstructing the past. The extent to which historians are able to practice their craft invariably depends on not just the quantity, but also the quality, of the sources at their disposal. On occasion, the richness of the archival record allows the life histories of obscure individuals to be reconstructed in considerable detail.19 In other instances, however, even the most astute reading of the archival record does not allow us to reconstruct various aspects of the human experience at the macro-regional, much less local, level.

HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY IN THE INDIAN OCEAN

The utility of the term “historical archaeology” in Indian Ocean studies was a subject of considerable discussion during the Stanford workshop. This is a topic that, beginning with the important work of Kent Lightfoot, has been much debated in archaeology, particularly when juxtaposed with prehistory, and continues to be a subject of discussion.20 For the wider Indian Ocean, archaeological research has tended to focus on evolutionary archaeology or prehistoric civilizations. Limited opportunities for historical archaeology in this oceanic basin can easily be traced to inadequate funding for archaeological research, a problem compounded by the region’s vastness and the complexity of patterns of interaction within it. Such an explanation is ultimately not particularly convincing, however, especially when we remember that an equally vast, diverse, and complex Atlantic world has long been a subject of extensive historical archaeological research. Such an explanation becomes even less satisfactory in light of what we now know about the Indian Ocean’s importance in global history and the history of globalization.

The development of historical archaeology as a discipline has strong connections to the Atlantic. In the United Kingdom and European Union, archaeologists have adopted chronological markers, such as “postmedieval,” and thematic framing, such as industrial archaeology. A useful point of departure is Charles Orser’s description of the subject as “text aided archaeology that uses a combination of archaeology and historical methods, sources, and perspectives to study the recent past.”21 However, for the Indian Ocean, as with many parts of Europe, Africa, and China, we must wrestle with the much deeper antiquity of the written word and the implications this has for defining historical archaeology in these settings.

As the workshop’s participants appreciated, the issue of periodization is central to defining what may or may not constitute “historical” archaeology in the Indian Ocean. The limited and often problematic nature of the textual sources at our disposal and the absence of the kind of commonly agreed upon chronological markers found in the Atlantic world make it difficult to apply Orser’s definition to the Indian Ocean world. As the archaeological record demonstrates, there is deeper diachronic continuity between cultures throughout much of the Indian Ocean world than is found in the Atlantic.22 The question often facing the historical archaeologist working in the Indian Ocean is not just, When does archaeology become historical, but also, Where does it do so? Even in cases such as Mauritius, where the point in time at which archaeology becomes historical is seemingly straightforward (i.e., when Europeans colonized this previously uninhabited island), the question of when Mauritian history begins can be problematic. That the island was subject to two periods of Dutch settlement and subsequent abandonment (1638–58 and 1664–1710) before being permanently colonized by the French in 1721 raises the question of which of these dates marks the “real” beginning of the Mauritian historical experience and, hence, of Mauritian historical archaeology. The point in time at which historical archaeology begins, or should begin, in other parts of this oceanic world is even more difficult to ascertain. Doing so requires us to confront a number of ethical as well as methodological questions: Is it appropriate to apply periodization schemes grounded in European history to reconstructing the past of peoples who were established in locales long before Europeans arrived on the scene?23 Is such a practice consistent ...