![]()

1

INCOMPLETE MONETARY UNION AND EUROPE’S CURRENT CRISIS

In the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, countries of the European Union (EU) faced economic calamities of a level not witnessed since the Great Depression. Gross domestic product (GDP) plummeted in some countries by over 25 percent of pre-crisis levels, unemployment rose sharply, and for the EU’s peripheral economies1 (Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain), interest rates on government bonds increased substantially as markets doubted the capacity of these sovereigns to repay public debts. Politically, between 2008 and 2012 alone, eight EU governments (Slovenia, Slovakia, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Romania, Ireland, and the Netherlands) collapsed between elections; two EU countries (Greece and Italy) introduced unelected, technocratic governments to manage their economies; and countries in the EMU North and South witnessed the decay of traditional party alignments as new extreme right and left parties arose to exploit popular frustration.

The EU also faced a pivotal legitimacy juncture as member-states that previously were supportive of the supranational polity are now questioning its value. Voters in southern economies have turned their backs on an EU associated with harsh austerity measures that have caused significant reductions in living standards (Matthijs 2014). Anti-EU parties have benefited significantly from this crisis, not only in national elections but also European Parliamentary elections, as far-right and far-left parties urge either the exit of the euro (Marine Le Pen’s National Front in France) or a “different Europe” (Beppe Grillo’s Five Star Movement in Italy) (Kundani 2014). While the EU’s political modus operandi as an elite-driven regulatory state (Majone 1994) may have survived during good economic times, its lack of democratic accountability, coupled with its imposition of devastating redistributionary policies on some member-states (most potently in the terms of Greece’s July 2015 bailout and Cyprus’s bank levy), is proving difficult to manage as a great number of EU citizens question the economic and political benefits of further integration.

European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), perceived as one of the boldest steps forward in European integration, has also come under heavy scrutiny. Many of the EU’s fledging economies lie within EMU’s boundaries and lack important economic instruments to adjust to the crisis. EMU was a major political project, driven by neoliberal and monetarist ideals of delivering low inflation in Europe (Streeck 2014). It was also an incomplete project. Of the three macroeconomic conditions required for a complete and functional currency union (centralized monetary policy, centralized fiscal policy, and labor market flexibility), EMU possessed only the first. Due to the unlikelihood of European fiscal union, labor market flexibility was perceived by many as the only feasible means of economic adjustment for countries facing asymmetric economic shocks in a currency union with a one-size-fits-all monetary policy (Eichengreen 1993). Yet even here, EMU did not possess the degree of labor market flexibility required for economic adjustment in the event of an asymmetric crisis (Sibert and Sutherland 2000; Puhani 2001). While European leaders hoped for the best at the start of the monetary union, the current debt crisis delivered the worst to Europe’s single currency, which, thus far, has witnessed little economic adjustment within its peripheral economies. Eight years after the global financial crisis, the South remains unable to reverse its economic misfortune.

How did EMU succumb to the serious economic crisis that it finds itself in currently? The U.S. subprime mortgage crisis and the 2008 global financial crisis have been acknowledged as critical catalysts of Europe’s crisis (Hellwig 2009; Martin 2011; Mishkin 2011). Expanding from this trigger event, however, public and academic debate has searched for factors before the 2008 financial crisis that may have contributed to crisis exposure in the periphery. The exponential rise of international capital flows and the failure of banks to properly assess default risks, coupled with lax regulation of lending practices, have been identified as one source of the crisis on the credit supply-side (E. Jones 2014 and 2015). Others have attempted to explain differences in the demand for lending and the accumulation of debt. One argument that gained traction early in public debates, especially among Europe’s policy elites and the “troika” (the EU Commission, European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund), is that the accumulation of pre-crisis public debt is to blame. Peripherial economies are exposed to crisis because of their reckless fiscal records before 2008, while EMU’s northern economies (Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, and the Netherlands, also referred to as the EMU core) were more fiscally responsible and therefore have been largely immune to speculative attack.

A second line of thought on the crisis’s origins connects divergence in speculative pressures in EMU’s North and South to persistent current and capital account imbalances (or differences in the accumulation of both public and private external debt). Advocates of this competitiveness hypothesis argue that the current crisis stems from the failure of EMU’s peripheral economies to control unit labor costs after the launch of the euro, which led to a rise in inflation, appreciating real exchange rates and persistent trade/current account deficits vis-à-vis EMU’s northern economies that successfully moderated national wage growth. This was not due to the significant rise in wage inflation in the periphery per se; the severe wage moderation that was produced by EMU’s northern export-led economies was also a major component of current account divergence within the Eurozone (Wyplosz 2013). To finance their current account deficits, peripheral economies borrowed externally (not just publicly, but also privately) from northern economies, incurring capital account surpluses.

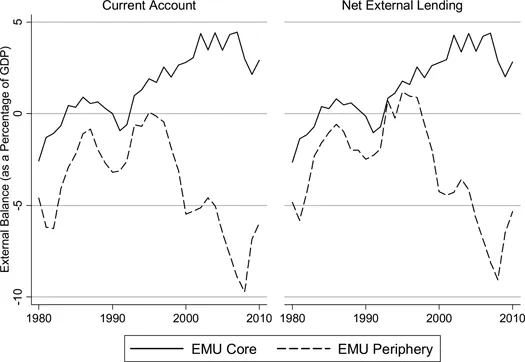

Such imbalances would not have been a persistent problem before monetary union, as nominal exchange rate movements could assist high-inflation economies with competitive readjustment. With relative rising unit labor costs and inflation, the nominal value of the national currency would decrease, improving exports and hindering imports. Such nominal exchange rate movements would also facilitate adjustment in a country’s demand for foreign capital, as more volatile exchange rates imposed higher interest rate premia on debt instruments, decreasing demand for external borrowing. Upon entering the monetary union, EMU’s member-states lost their national exchange rates as adjustment mechanisms for current and capital account imbalances, and these deficits grew persistently over time (see figure 1.1). Once the global financial crisis hit, markets perceived these current account deficits and capital account surpluses as unsustainable, prompting an exodus of capital from the South as investors became worried about possible default.

The substantial worsening in external lending and trade imbalances between EMU’s northern and southern economies have been cited by economists and policymakers as crucial determinants that separated EMU’s strongest from its weakest links (Bernanke 2009; Obstfeld and Rogoff 2009). Countries that were overexposed in external borrowing and consumption were those that were picked off by markets first in the flight to quality. However, what is more conspicious about these growing and gaping external imbalances between EMU’s member-states is that they were largely limited to the years of the single currency (see figure 1.1). Historically, EMU’s northern economies produced healthier current account and net external borrowing balances than their southern neighbors, but differences in external macroeconomic performance between the two regions only became egregious once monetary union came into play.

FIGURE 1.1. External imbalances between the EMU core and peripheral economies (1980–2010)

Note: EMU core includes Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, and the Netherlands. EMU periphery includes Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. Net external lending data prior to 1995 excludes Greece (for which data was unavailable until 1995).

Source: EU Commission AMECO Database (2014).

In this book, I argue that this recent rise in the external imbalances of EMU’s member-states under monetary union is not coincidental. The general argument I propose is that EMU’s current crisis, and the growing external imbalances between its member-states that helped produce it, is a direct consequence of structural flaws in the governance of labor markets that are present in EMU’s institutional design. In examining the impact of supranational institutional shift on national governance and economic outcomes, I dissect two empirical puzzles that are present within Europe’s current sovereign debt crisis: 1) why EMU’s core economies have emerged from the crisis with little speculative pressure, despite the fact that some of these economies had poor pre-crisis fiscal records, while EMU’s peripheral economies have encountered heavy speculation, despite the fact that some produced consistent budgetary surpluses in EMU’s pre-crisis years, and 2) why the persistent growth in current and capital account imbalances between EMU’s core and periphery was a phenomenon that was largely restricted to the EMU period.

I argue here that Europe’s monetary union, in line with its neoliberal and monetarist origins, was structured in such a way that advantaged its low-inflation performers. The common currency’s new real exchange rate calculus, which, with the disappearance of nominal exchange rates between member-states, became solely a function of relative inflation, provided countries that could consistently produce low inflation with a persistently competitive real exchange rate and, in turn, growing current account surpluses. However, EMU’s low-inflation bias was not solely present in the construction of the real exchange rate for its member-states. EMU also removed two pivotal institutions that were responsible for increasing inflation-aversion in the domestic labor markets of its peripheral economies: national level inflation-averse central banks and fiscal rules with significant compliance penalties (the exclusionary nature of the Maastricht deficit criteria).

Though labor markets were acknowledged as perhaps the only realm of economic adjustment under Europe’s single currency, member-states’ diverse wage-setting institutions were neglected during European monetary integration, which had serious consequences for the stability of the euro. Monetary union’s contribution to the current crisis can be partially explained by how it altered inflation dynamics in its member-states through the altercation of sectoral wage-setting politics within nation states. Before monetary union, wage-setters in both sectors exposed to trade, where incentives for wage moderation are high, and in sectors sheltered from trade, where wage moderation incentives are not as prominent, were disciplined in their wage-setting strategies by national central banks that upheld either formal or informal low-inflation mandates. The ultimate result of this institutional movement toward the mass adoption of inflation-averse central banks, which was heavily reinforced by the Maastricht nominal criteria, was an unprecidented level of inflation and real exchange rate convergence among EMU candidate countries. As a consequence of inflation and real exchange rate convergence, external imbalances between current EMU member-states were contained before 1999.

Under EMU, wage-setters within national economies did not encounter similar wage discpline by inflation-averse monetary authorities. National central banks were more easily able to target sectoral wage-setters if they produced inflationary wage settlements, as these actors constituted a significant share of these banks’ inflation target. The same could not be said of the European Central Bank (ECB), whose mandate applied to the Euro-area as a whole rather than individual nation-states.2 What emerged in the new politics of national wage setting across EMU’s member-states was a collective action problem in the exertion of wage moderation—because monetary authorities could no longer penalize sectoral or national wage-setters if they produced wage inflation, incentives to pursue inflationary settlements increased. Yet wage inflation did not emerge en masse across and even within EMU member-states. Wage-setters in tradable goods and services sectors continued to exert wage moderation because of the output and employment consequences of wage inflation in the presence of high market competition.

Wage inflation in nontradable sectors, on the other hand, exhibited wide heterogeneity across EMU member-states. In EMU’s peripheral economies, wage increases in nontradable sectors outpaced those in the tradable sector, placing upward pressures on inflation. In EMU’s core economies, heavy wage moderation in nontradable sectors was maintained because these economies possessed coordinated corporatist institutions that limited nominal labor cost growth. Domestic politics in EMU’s export-oriented core economies have historically been aligned toward inflation-aversion, and wage-moderating labor market institutions reflect this. EMU’s core economies entered the single currency with their long-established national collective-bargaining institutions, which granted agenda-setting and veto powers to wage-setters in their export sectors. These institutions enabled the EMU core to moderate national, and sheltered sector, wage growth in order to promote their trade-surplus-prone export growth models. In contrast, labor market politics in the EMU’s southern economies, given their more confrontational and fragmented nature, traditionally have not been conducive toward wage moderation and low inflation, particularly within nontradable sectors. However, EMU’s institutional predecessors—the European Monetary System (EMS) and the Maastricht criteria—promoted converging inflation trajectories between these diverse labor markets by standardizing the monetary and EMU-conditionality penalities associated with high (sheltered sector) wage inflation.

EMU was a distinct break from this regime. Once common monetary and fiscal constraints were removed in 1999, the true “inflationary” nature of the periphery’s labor market institutions was allowed to organically unfold. These economies did not witness a significant resurgence in absolute wage inflation. EMU’s peripheral economies witnessed lower inflation rates under EMU than they did in the 1980s and 1990s. Rather, relative inflation divergence was largely facilitated by severe wage moderation in the EMU core, promoted by its export sector favoring labor market institutions (Wyplosz 2013). With comparatively higher inflation rates, southern economies quickly lost competitiveness in their real exchange rates, leading to the persistent, and ultimately unsustainable, accrual of current account deficits vis-à-vis the North and the need for international borrowing to finance these deficits. The rising imbalances between EMU’s northern and southern economies that helped precipitate crisis exposure within the latter can therefore be understood by how EMU created an unbalanced playing field between countries with wage-setting institutions prone to low inflation and countries lacking these institutions.

Calm before the Storm: Inflation and Wage Growth Convergence before Monetary Union

In political economy debates about inflation, many acknowledge that some industrial sectors are more prone to low inflation than others. Within national labor markets, the delivery of low national inflation through moderated wage growth is dependent on power dynamics between conflicting sectoral interests. Several have outlined how the dualistic nature of wage setting in sectors exposed to and sheltered from trade3 influences national price developments (Crouch 1990; Iversen 1999a; Garrett and Way 1999; Franzese 2001; Traxler and Brandl 2010). These national price developments, in turn, influence exchange rate patterns and the trade competitiveness and external borrowing balances of countries.

Employers (and unions) in the exposed sector (i.e., manufacturing) are more likely to establish low wage settlements than their sheltered counterparts, as their output and employment are more sensitive to cost-induced price changes given the presence of multiple competitors in international markets. Unions in sectors sheltered from trade (e.g., the public sector, most services sectors, and construction) bargain with employers who face more lax competitiveness constraints and, in the case of public employers, softer budget constraints in their capacity to run deficits. Consequently, sheltered sector unions have greater political capacity to push for higher wages than their exposed sector counterparts. Because these sheltered sectors constitute a significant proportion of the national labor force, their inflated wage settlements influence aggregate wage growth and ultimately prices. This implies that the sheltered sector’s incapacity to deliver wage moderation has important implications for inflation and, through the real exchange rate, international price competitiveness.

Despite these theoretical predictions, however, current EMU countries witnessed a surprising reduction in real wage growth in the sheltered sector during the 1980s (for most of EMU’s northern economies) and the 1990s (for EMU’s southern economies), as sheltered sector employers and governments succeeded in imposing a prolonged series of wage freezes and wage cuts on their workers. Figure 1.2 presents three-year moving averages in wage moderation (the difference in sectoral real hourly wage growth and productivity growth), for the exposed manufacturing sector and the sheltered services sector of countries in EMU’s first entry wave, the EMU10 (appendix I provides formal details on how wage moderation is measured, as well as details on the sectoral proxies).4 Contrary to EMU, where the manufacturing sector witnessed significant wage moderation while the sheltered sector experienced wage inflation, under the European Monetary System (1979–1998) and Maastricht period (1992–1998), differences in wage moderation exerted in both sectors were largely contained.

A similar story emerges when comparing sectoral wage developments between the EMS/Maastricht and EMU periods, in absence of productivity developments. Figure 1.3 presents differences in annual wage growth between the exposed manufacturing sector and the sheltered services sector for three periods: the pre-Maastricht EMS period (197...