eBook - ePub

Coping with Uncertainty

Youth in the Middle East and North Africa

- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Coping with Uncertainty

Youth in the Middle East and North Africa

About this book

Seven years after the Arab uprisings, the social situation has deteriorated across the Middle East and North Africa. Political, economic and personal insecurities have expanded while income from oil declined and tourist revenues have collapsed due to political instability. Against a backdrop of escalating armed conflicts and disintegrating state structures, many have been forced from their homes, creating millions of internally displaced persons and refugees. Young people are often the ones hit hardest by the turmoil. How do they cope with these ongoing uncertainties, and what drives them to pursue their own dreams in spite of these hardships? In this landmark volume, an international interdisciplinary team of researchers assess a survey of 9,000 sixteen- to thirty-year-olds from Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, Syria, Tunisia and Yemen, resulting in the most comprehensive, in-depth study of young people in the MENA region to date. Given how rapidly events have moved in the Middle East and North Africa, the findings are in many regards unexpected.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Coping with Uncertainty by Joerg Gertel,Ralf Hexel,Jörg Gertel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Middle Eastern Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

HABITS & VALUES

3

Values

Jörg Gertel & David Kreuer

VALUES ARE POINTS of reference for human behaviour. In this chapter, we examine the importance of the values and aspirations of young people in the MENA region. We explore how stable their values are, given the multiple crises and on-going disruptions in Middle Eastern societies. In the 1990s, Bennani-Chraïbi (1994) first described identity formation among Arab youth as bricolage culturel (cultural assemblage). The term captures the combination of identity fragments resulting partly from values and beliefs considered ‘traditional’, and partly from ‘modern’ cultural references including creative strategies for coping with recent social and economic problems and challenges. Since then, the requirements of society have further increased for them. Current prerequisites include a greater readiness for mobility, spontaneity, assertiveness, and independence, but above all flexibility, creativity, velocity, and problem-solving skills. Entering the world of paid employment now demands such key competencies as loyalty, reliability, discipline, and thoroughness. In some instances, the actors may also need special linguistic or social skills as well as the ability to navigate religious and regional configurations. Many young Arabs have thus become flexible crafters of their own identities and biographies in these multifaceted worlds.

Today, new normative points of reference have emerged in biographical narratives in Arab countries. This is due to accelerated globalisation, omnipresent communication networks, and disturbing experiences of visual and physical violence. In the context of increasing uncertainty and widespread insecurity following the Arab Spring, a central question is how the loss of opportunities and reliable institutional anchors might affect young people’s values. We consider values to be suppliers of socially and personally desirable choices and patterns for self-orientation (Fritzsche 2000):

[Values] are not concrete prescriptions for action, not norms, and they are neither binding nor compulsory. Values are individual concepts of what is worth aspiring to. As such, they are rather general points of reference by which human behaviour can be oriented; but [it] does not necessarily have to . . . While norms are primarily effective between people and structure our behaviour . . . values are ‘in’ people. (Ibid.: 97, our translation, emphasis in the original)

Our exploration of values is presented in four sections. We start by introducing the young people interviewed. We then explore and discuss their value sets. Next we discuss correlations and clusters of values that connect groups of youth beyond national borders, and then we focus on the impact of societal ruptures and young people’s anxieties, shedding light on individual discontinuities and the transformation of values.

Characteristics of Arab Youth

Arab youth and young adults were interviewed across eight countries in the summer of 2016. They are aged 16–30, and the majority still live with their parents. Just under a third of them, however, have already established a household of their own. This is particularly the case for women, who tend to marry at a younger age than the men of their generation. Despite this, almost all of them self-identified as ‘youth’ (91 percent of females, 93 percent of males) rather than ‘adults.’ Almost all of them have a very strong connection to their parents: they live with their parents, and often also eat together; two-thirds still belong to the same unit of reproduction, meaning that they can have their own spending money, but a large share of household members’ income is pooled in a common budget. Even in the case of young adults with their own household, they retain numerous connections to their parents (see Chapter 7). The key characteristics used in the following to describe the youth are their level of education, language skills, class status, involvement in social networking, life goals, and views on the importance of family, children, and intergenerational relationships as well as their sense of belonging. These characteristics are closely tied, we argue, to shaping young people’s values.

Education

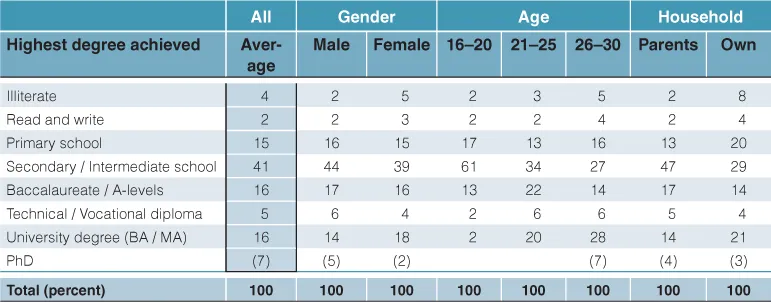

Investigating education is not particularly easy. For one, some respondents are still in the midst of their training and education. Moreover, school enrolment rates have sometimes changed dramatically (often increasing) within just a few years, rendering comparisons across groups somewhat problematic, particularly when an entire region, not just a single country, is considered. What is the general and overall educational status of the interviewees? When three groups with the lowest formal education are clustered together – namely, the illiterate, people who can read and write but have no formal education, as well as those who have no more than a primary school education – one finds that as much as one-fifth of respondents have only a minimal formal education (Table 3.1). The large majority, however, have had secondary school educations. Corresponding to their age, one segment of interviewees is still in (vocational) training, while the older ones might have already graduated and are working, either unpaid (e.g. work as housewife) or in paid employment. Therefore, age is important in assessing educational levels.

Table 3.1 Youth and Education

Questions 3, 4, 15, 26.

Note n=9,000 · Figures are given in percentages. Rounding errors can occur. | ‘Household Parents’ = Interviewee lives with parents in the same household; ‘Household Own’ = Interviewee has established own household. Figures in brackets represent single cases.

When age is applied, the youngest group (aged 16–20) has by far the highest proportion of secondary and intermediate-level students, and only a small number has more than a high school diploma. The middle group (aged 21–25) shows a much broader distribution of educational degrees. In the oldest group (aged 26–30), among which many have completed their education and training, we find the greatest polarity: one-quarter have no or only minimal formal education, while three-quarters have completed higher education (more than one-quarter holding university degrees). This polarity is even more pronounced among those who have established their own households. Overall, a pattern emerges that is known from other studies: enrolment rates and education levels have generally improved over time. The difference between countries, however, is considerable. A comparison of the average number of school years completed shows Bahrain, Tunisia, Palestine, and Lebanon in the lead, with an average of twelve or thirteen years of school, followed by Jordan, Morocco, and Egypt, with an average of ten to eleven years of education. The lowest averages are eight years of schooling in Yemen and seven years for Syrian refugees in Lebanon.

Language skills

Almost all surveyed youth (99 percent) cite Arabic as their native language. Of note, spoken Arabic dialects differ greatly from one another in terms of vocabulary, pronunciation, and even grammar. It is only the written language, namely Modern Standard Arabic, which is taught in schools, that guarantees a speaker the ability to communicate across national borders. Second native languages, following far behind Arabic, are English (2 percent, mainly in Lebanon), Amazigh (only in Morocco), and French (primarily in Morocco). As regards a second language that young people master, English comes in first place (34 percent), clearly ahead of French (18 percent). This situation is reversed in Morocco and Tunisia (combined, 55 percent French, 29 percent English), as both countries historically have strong ties to France.

Class status

Social stratification is distinct from country to country. To understand the different access to resources, we calculated a ‘social strata index’, based on four criteria: educational status of the father, wealth ranking of the household, housing situation, and economic self-assessment (see Chapter 2). The higher a respondent’s and his or her family’s score in these areas, the higher their social status. Our analysis reveals some pronounced differences: the higher the social stratum, for instance, the greater the proportion of younger and single rather than older and married persons. Members of the lower strata tend to feel less secure and have less optimism for the future.

Social networks

Three-quarters of those surveyed use the internet, and almost half of them have an internet connection in their home. Such social networks as Facebook and WhatsApp are used primarily to connect with family and friends (75 percent of users) and only rarely for political (9 percent) or religious mobilisation (ta‘bi’a) (13 percent). Three-quarters of those interviewed own a smartphone. At the same time, more than half are part of a fixed circle of friends, and almost all are satisfied or very satisfied with those friends. One in seven respondents, however, is not part of a group of friends and does not have access to the internet. This situation is most common among Syrian refugees in Lebanon and young people in Yemen and Morocco. Generally, the strongest feelings of attachment are to ‘offline institutions’, that is, their family (average ranking of 8.2 on a scale 1–10), home region (average of 7.1), and religious community (average of 7.0). Young people without internet access tend to have higher scores here. On the other hand, it is the internet users who feel a greater connection to young people in the rest of the world, in particular through common interests in fashion (35 percent), football (34 percent), and music (32 percent). This can be further broken down by gender. Males dominate as regards interest in football (49 percent of males compared to 18 percent of females) and computer games (34 percent to 24 percent), while the connection through fashion is more markedly female (39 percent to 30 percent).

Life goals

Asked to choose one individual goal from a list of four possible choices, almost half of respondents opted for ‘a good job’, almost one-third for ‘a good marriage’, and just under one-fifth for ‘good family relationships’ (Table 3.2). This points to the central importance of work and the hope of a fulfilling future associated with employment. The differences between men and women are, however, remarkable for the first two goals. Almost two-thirds of men opted for a good job compared to one-third of women. This corresponds with the current labour market situation in which men continue to be the main earners, and women engage in paid work primarily as a temporary activity. Those women often seek employment during the period between graduation and the onset of new demands with the establishment of an independent household (see Chapter 7). In particular, women often switch back to unpaid work in the home after having children. Subseque...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface, Ralf Hexel

- Introduction

- Part I: Habits & Values

- Part II: Economy

- Part III: Politics & Society

- Part IV: Comparing Youth

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgements

- About the Authors