![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction: Impact Evaluation for Evidence-Based Development

Key Messages

• Impact evaluation empirically estimates the effects attributable to a specific intervention and the statistical significance of those effects.

• Deriving reliable knowledge and evidence from development operations depends on impact evaluation.

• Impact evaluation can serve a number of roles. It can determine not only whether an intervention is effective, but it can also compare options for making interventions more effective.

• Evidence from impact evaluation can inform assumptions underpinning economic analysis of specific investments, as well as broader strategies for sectors, regions, and countries.

1.1 Why Does Impact Evaluation Matter?

Development organizations have an ultimate mandate to contribute to development goals. For example, Strategy 2020 of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) reaffirms ADB’s vision of an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. ADB’s mission is to help developing member countries improve living conditions and the quality of life of their citizens. To this end, billions of dollars of funding are mobilized each year. What have been the impacts of the funded programs?

The answer to this question requires evidence that is produced by “counterfactual” impact evaluations (IEs). Without IE, it is not possible to ascertain the causal effects of development interventions. In the absence of understanding what effects have occurred as a result of development efforts, it is neither possible to keep accountability about development expenditures, nor to derive meaningful knowledge from development operations to improve development policies.

Impact evaluations are empirical studies that quantify the causal effects of interventions on outcomes of interest. This is far different from traditional process evaluations that are concerned with characterizing how projects were implemented. IEs are based on analysis of what happened with an intervention, compared with an empirically estimated counterfactual scenario of what would have happened in the absence of the intervention. This difference between the observed outcomes and the counterfactual outcomes is the measure of impact, i.e., the difference that can be attributed to the intervention. Effects can be quantified at any level and, contrary to popular perception, do not need to concern only long-term goals or “impacts” in the jargon of logical frameworks. At the same time, IE is the only method that can provide evidence as to those long-term effects.

IE is unique in that it is data driven and attempts to minimize unverifiable assumptions when attributing effects. A core concept is that identified impacts are assessed not only in magnitude, but also in terms of statistical significance. This approach is not to be confused with “impact assessment,” which often includes modeling rooted in taking structural and often neoclassical assumptions about behavior as given, and which cannot ascertain statistically significant effects.

Development assistance’s drive toward evidence-based policy and project design and results-based management depends on mainstreaming IE. IE allows for assumptions underpinning the results logic of interventions to be tested and for previously unknown consequences to be revealed.

At the heart of evidence-based policy is the use of research results to inform and supplant assumptions as programs and policies are designed (Sanderson 2002). In turn, this depends on the generation of new evidence on effectiveness, and the incorporation of evidence into program conceptualization. One linkage by which this can be achieved is by informing economic analysis of investments. IE validates and quantifies the magnitude of the effects of an intervention, and these effect magnitudes are critical to understanding project benefits. The impact findings for one intervention can inform the economic analysis for a follow-on project to scale up the investment, or for similar investments elsewhere.

One of the best known examples of evidence-based policy in international development has been the growth of conditional cash transfers (CCTs) in Latin America (Box 1.1). Similarly, an ADB-supported IE of the Food Stamps Program in Mongolia played a part in persuading the government to scale up the program (ADB 2014).

Box 1.1: The Use of Evidence from Impact Evaluations to Inform the Spread of Conditional Cash Transfers in Latin America

The conditional cash transfer (CCT) program, PROGRESSA, was started by the Mexican government in the mid-1990s. The government decided to build a rigorous, randomized evaluation into the program design. The study showed the positive impact of CCT on poverty and access to health and education. These findings meant that the program survived a change in government with just a change in name. A similar story can be told about Colombia’s CCT, Familias en Acion. In Brazil, the President commissioned an impact evaluation of the Bolsa Familia program to be able to address critics of the program, especially those who argued that it discouraged the poor from entering the labor market. The study showed it did not, and Bolsa Familia continued to expand, reaching over 12 million families by 2012.

Source: Behrman (2010).

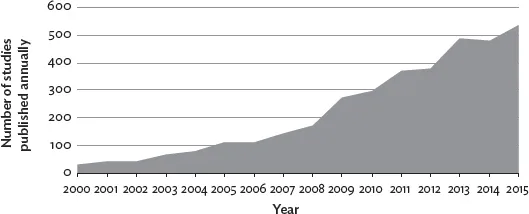

The IE movement has spread across the world and across sectors (Figure 1.1). A database of over 4,000 development IEs shows this rapid growth, with 500 new studies a year by 2015. Most of these studies are in the social sectors, but there are growing numbers for many other topics, such as rural electrification, water supply, and transportation.

Figure 1.1: Annual Publication of Impact Evaluations

Sources: Cameron, Mishra, and Brown (2016); authors’ estimates from the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie) impact evaluation repository.

1.2 The Purposes of Impact Evaluation

IE, like other forms of evaluation, has two principal purposes. The first is accountability, so as to ensure that development actions actually lead to development outcomes. The second is learning, so as to offer an evidence base for selecting and designing development interventions that are likely to be effective in fostering outcomes of interest.

Both purposes are manifest in important trends, to which development agencies must respond. A range of policy makers and stakeholders have been stepping up requirements for rigorous demonstration of results from development finance (OECD 2011). This is starting to drive resource allocation toward agencies and programs that make an effort to credibly estimate whether expected outcomes and effects actually occur as a result of their interventions.

There is also increasing demand from a range of stakeholders that policy and investment proposals reflect insights based on systematic use of evidence (Parkhurst 2017). Development agencies can be responsive to these requirements, by both (i) presenting earlier IE results in their project/sector experience, and (ii) promoting new pilot initiatives that include IE as a systematic means of testing innovations. By doing so, agencies position themselves as “knowledge” institutions of reference in their respective sectors.

Multilateral development banks, notably the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank, have been important players in the rise of IE. The World Bank has various programs to provide technical and financial support to IE, including a Strategic Impact Evaluation Fund. By 2013, all new loan approvals at the Inter-American Development Bank included an IE in their design. In 2014, the African Development Bank has developed a new policy that requires more IEs.

ADB has joined this movement through various activities. Recently, ADB established substantial technical assistance funds to resource additional IEs. This book is to serve as a tool for project staff, government partners, and other development practitioners who may be interested to include IEs in their projects, generate evidence from other related interventions, or understand how to use IE findings.

1.3 What Questions Can Impact Evaluation Answer?

IE answers questions, such as (i) what difference does a policy or program make?, or (ii) which program designs are more effective for one or more specific quantifiable outcomes? It can also offer understanding of how those outcomes differ among different populations and what factors condition those outcomes.

The central role of counterfactual analysis

IEs are designed to address the causal or attribution question of effectiveness: did the intervention make a statistically significant difference to specific outcomes? Answering this question requires a counterfactual analysis of an alternative scenario in which the intervention did not occur, where that alternative may be no intervention, or an alternative intervention (a so-called A/B design as it compares intervention A with intervention B). Establishing the counterfactual is the core challenge of IE. This is because, while the actual scenario is directly observed, the counterfactual is usually not. Despite this challenge, counterfactual analysis is necessary to establish which programs are most effective, or indeed whether a program makes any difference at all.

Impact evaluation questions

IE is the only way to test, empirically, the extent to which project and policy initiatives produced measurable differences in outcomes compared with counterfactual estimates (i.e., in the no intervention scenario)...