![]()

1. Introduction

A. Disaster Profile and Trends in Asia and the Pacific

Urgent action is required to strengthen disaster resilience in Asia and the Pacific. Disasters threaten sustainable socioeconomic development. They harm lives, damage infrastructure, and destroy productive capacity, with potentially significant consequences for wider economic and social aggregates such as gross domestic product (GDP), balance of payments, budget deficit, and poverty incidence. Reflecting the significance of this threat, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by 193 countries at the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Summit in September 2015 explicitly target risk reduction under 4 of its 17 goals (UNISDR 2015).1 The developing member countries (DMCs) of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) need support in strengthening resilience as part of their efforts to achieve the SDGs and also to meet their commitments under the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, another part of the post-2015 agenda for sustainable development (UN 2015).

Despite significant advances in tropical cyclone and flood forecasting and early warning systems, overall levels of disaster-related mortality have failed to decline over the past 4 decades in Asia and the Pacific. To some degree, this can be attributed to a number of highly destructive earthquakes and tsunamis during the first decade of the new millennium (ADB 2013). Over 360,000 lives were lost as a consequence of natural hazards during 2006–2015 in Asia and the Pacific, close to levels in the 3 previous decades. About 93% of these fatalities occurred in DMCs. Over the same period, 1.4 billion people were affected by natural hazards in the region, of which 98% were in DMCs.

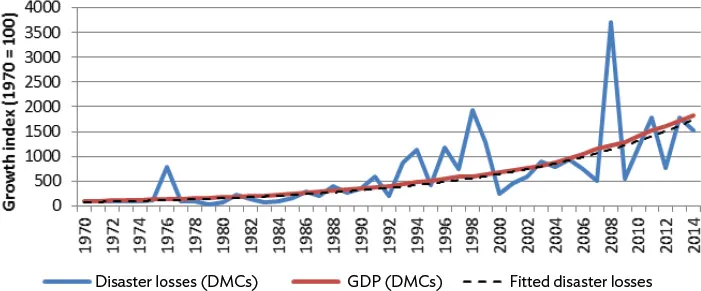

Meanwhile, direct physical losses have steadily increased in recent decades both globally and in Asia and the Pacific (Figure 1). Direct physical losses totaled $727 billion in 2006–2015 in Asia and the Pacific. ADB’s DMCs alone experienced losses of $461 billion, equivalent to an average loss of $126 million per day. Over a longer period stretching back to 1970, growth in direct physical losses as a consequence of natural hazards in ADB’s DMCs has matched growth in GDP, reflecting insufficient regard to disaster risk in either the design or location of infrastructure, homes, and other assets. With the expected rise in intensity and, in some areas, frequency of climate-related hazards as a consequence of climate change and a steadily growing concentration of people, assets, and services in hazard-prone areas, including coastal cities, growth in direct physical losses could easily overtake growth in GDP in DMCs unless urgent action is taken.

Figure 1: Direct Physical Losses as a Consequence of Natural Hazards in ADB’s Developing Member Countries, 1970–2014

ADB = Asian Development Bank, DMC = developing member countries, GDP = gross domestic product

Source: ADB.

Indeed, disaster losses may already be increasing in excess of GDP growth as actual losses may be higher than available data suggests. Frequent but low intensity and localized hazards (such as localized flash floods, landslides, and storms) are often underreported in national and international disasters statistics. Recent global analysis suggests that the aggregate impact of these small-scale events on agriculture, roads and most public utilities is significantly higher than that of large-scale natural hazard risks (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction [UNISDR], 2015). It is estimated that, worldwide, 98% of damage to water supply and energy, 93% of damage to agricultural crops, and 81% of damage to roads are caused by such low-intensity risk hazards. As most of these localized hazards are weather-related, their overall incidence is likely to further increase with climate change.

B. Disaster Risks and Development in Asia and the Pacific

Disaster risk is the result of the interaction of natural hazards and of the exposure of vulnerable people and assets to these potential natural hazard events. Development processes have a potentially important impact on levels of exposure of people and assets to natural hazards, and their degree of susceptibility or resilience. For instance, development often modifies existing patterns of land use, changing the exposure to natural hazards, and, possibly, vulnerability. Some development decisions have destroyed natural ecosystems that acted as a barrier against floods, storms, and landslides such as forests, wetlands, and mangroves (ADB 2013). Industrial development has often increased the number of exposed and vulnerable populations and assets in hazard-prone areas.

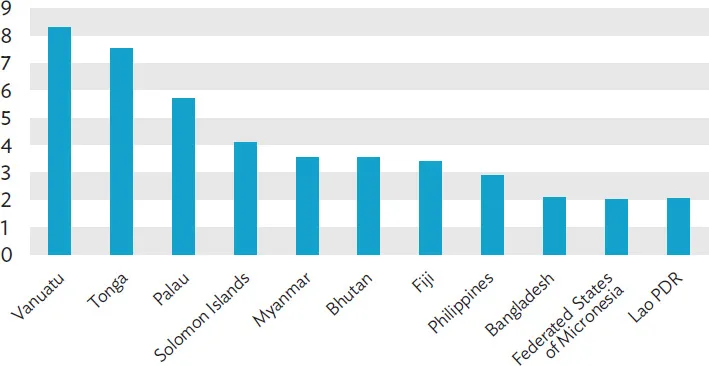

In Asia and the Pacific, the highest average annual losses (AALs)2 from multiple natural hazards are concentrated in larger, higher-income economies such as Japan. However, if AAL is measured relative to economic aggregates such as GDP, the value of capital stock or annual capital investment, many low- and middle-income countries have much higher levels of risk (UNISDR 2015). Indeed, disaster risk presents a serious threat to inclusive development in many of ADB’s DMCs. Eleven DMCs face AALs in excess of 2% of GDP while 21 face AALs in excess of 1% of GDP. Small island developing states in the Pacific fare particularly badly (Figure 2). Countries with low levels of growth and investment find it very difficult to replace capital stock following a disaster. Lost assets and investments further hamper economic development and sustainable growth.

Figure 2: Highest-Ranked Developing Member Countries According to Average Annual Loss as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product

Lao PDR = Lao People’s Democratic Republic.

Source: Based on data from UNISDR (2015). http://www.preventionweb.net/english/.

Moreover, the destructive impact of natural hazards goes well beyond direct human and physical losses. These direct losses have indirect flow consequences, disrupting livelihoods, jobs, and the provision and uptake of services such as health care, education, supply changes, and markets.

Disasters have a particularly detrimental impact on the poorest members of society, widening income and gender disparities and affecting the nutritional, health, and educational status of this group disproportionately. The poor are more likely to (i) lose places of work, homes, tools, crops, and years of schooling; and (ii) typically have highly limited access to savings, credit, or insurance to restore their assets (ADB 2013). AALs represent an important fraction of, or even exceed, annual social expenditures in many low- and middle-income countries. For instance, AAL represents 69% of annual social expenditure in the Philippines and exceeds it by a factor of two in Myanmar (UNISDR 2015).

The direct and indirect physical and social consequences of disasters can affect fundamental economic indicators such as the fiscal balance, trade balance, external reserves, national indebtedness, inflation, and GDP growth rates. It is widely observed that disasters cause significant short-term economic disruption for immediately affected communities. Longer-term impacts depend on a range of variables, but major disasters typically constitute significant economic shocks, knocking economies off course and potentially forcing them onto lower long-term growth trajectories. For example, disasters experienced in the Pacific over the period 1980–2014 reduced average trend growth in GDP from 3.3% to 2.6%, according to analysis by the International Monetary Fund (Cabezon et al. 2015).

Disasters can place significant pressure on public finance caused by both loss of revenue (e.g., via a decline in productivity and disruption of revenue collection) and additional spending (e.g., repair or reconstruction of public assets; relief and recovery to affected households and businesses). The capacity of government to deal with additional spending demands has important consequences for the pace and quality of recovery. Insufficient availability of timely financing for postdisaster response can result in slow and sluggish recovery, in turn exacerbating the indirect social and economic impacts of disasters, often with particularly detrimental cost to the most vulnerable and poorest segments of the population. Significant reliance on ex post funding can also mean that the impacts of a disaster continue to be felt for many years after the event.

C. Disaster Risk Management at ADB

ADB’s Strategy 2020 identifies disaster and emergency assistance as one of its other areas of operations, reflecting the considerable challenge that natural hazards pose to development in Asia and the Pacific (ADB 2008). The Midterm Review of Strategy 2020 reemphasized the importance of strengthened disaster resilience (ADB 2014a).

ADB’s disaster risk management (DRM) approach, as outlined in its Operational Plan for Integrated Disaster Risk Management, 2014–2020, recognizes that there is nothing inevitable about the impact of a natural hazard event (ADB 2014b). Many development actions carry potential disaster risk (by increasing exposure and/or vulnerability), but also provide opportunities to strengthen resilience. There is a wide range of potential structural and nonstructural risk reduction measures that can be embedded in development investments to strengthen resilience. Actions can also be taken to enhance disaster preparedness (including financial preparedness) and response capabilities, thereby supporting more rapid recovery and so reducing the indirect and secondary consequences of direct physical damage.

To ensure that these opportunities are reaped, DRM should be integrated into government development policies and plans, as well as individual investments in hazard-prone countries. It should also be considered in development assistance, subject to discussion with the country authorities. For ADB, this may begin with the country partnership strategy (CPS). The CPS serves as the primary relationship document between a DMC and ADB (ADB 2016a). CPS preparation and implementation provide opportunities to initiate a dialogue with DMCs on DRM issues, and to factor DRM considerations into ADB assistance.

Country teams may facilitate this process by developing and maintaining national DRM assessments as part of the CPS country knowledge plan. DRM assessments can provide an understanding of levels of disaster risk, the root causes of disasters and possible consequence of climate change, the impact of disasters on the pattern and pace of socioeconomic development, and opportunities to strengthen disaster resilience. DRM assessments are recommended for countries with medium and high disaster risk, but are not mandatory.

As a broad rule of thumb, countries with AAL in excess of 2% of GDP according to the latest available global data may be considered as having a high disaster risk (Appendix 1). Those with AAL equivalent to between 0.8% and 2% of GDP may be considered medium-disaster-risk countries. However, an element of judgment is required, particularly pertaining to countries with low AALs that are nevertheless located in seismically active areas where major earthquakes periodically occur, centuries apart, causing significant loss. ...