![]()

1

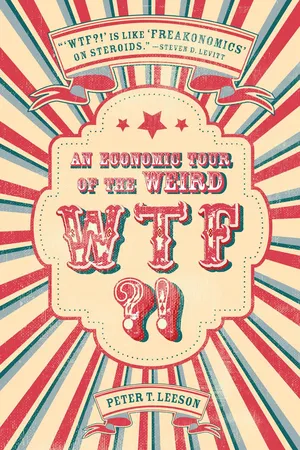

Your Favorite Acronym

“WTF?!” in its fully articulated glory, is probably one of your favorite exclamations. You say it often and think it more often still.

“WTF?!” captures the combination of bewilderment, astonishment, and perplexity you feel when you experience something unexpected, disconcerting, and, well, weird.

You realize that sea-monkeys have no relation whatsoever to actual monkeys.

“WTF?!”

Mr. Peanut’s doppelganger just stole your purse.

“WTF?!”

Marzipan.

“WTF?!”

Welcome, officially, to WTF?! the economic tour of the weird that will make you say “WTF?!” Our museum of social oddities is stocked with human practices certain to shock and amaze. Whether you’re a gorehound or a romantic, antiquarian or modernist, saint, sinner, animal lover, or anything in between, we’ve got something just for you.

I hope you didn’t come expecting ephemera, though. Our museum houses no fleeting fripperies or frivolous flashes in the pan. The bizarre practices you’ll find exhibited here lasted for centuries—some are still in use—and were, or are, central to organizing humanity’s most important social affairs.

Remember me from the lobby? I’m Pete, your tour guide, here to help you find your way literally and figuratively through the museum. The museum itself is a bit of a maze; you can thank the zoning board for that. But I know every nook and cranny, so I’ll get you where you need to go.

As to the social practices on exhibit: they’re going to seem . . . bat-shit crazy. My goal is to help you see the sense in their seeming senselessness.

To that end, before we get started, let me give you this tool you’re going to need.

[begins distributing tiny slips of paper to the crowd]

[The patrons, looking at the slips, have puzzled looks on their faces; irritated, one of them interrupts.]

“My card just says ‘Rational choice theory’ on it.”

They all do. You may not have been paying attention as we gathered in the lobby. Or maybe some of you were late. But that’s your tool. With it, and a bit of assistance from me, “WTF?!” will morph into, “That’s reasonable,” before your very eyes!

[An exasperated patron blurts:]

“WTF?!”

Your new tool is incredibly simple to use, so simple it’s sometimes unkindly likened to a hammer by people who’ve been trained to operate unnecessarily complicated contraptions. Pay no mind to such trash talkers. They’re just jealous, and like my hammer, this tool has always worked just fine for me.

Now, let’s read the instruction manual. Please turn over your slips.

[The crowd members turn over their pieces of paper. The irritated patron from before interjects:]

“Mine just says, ‘Think in terms of incentives.’”

I told you it was simple to use.

Incentives are the reason you go to work on days when you’d rather stay home or the reason you’re playing hooky right now. Why you paid to get into this museum instead of sneaking in—right? And why the fine folks at the Department of Motor Vehicles take their sweet, sweet time: I’ll just take my auto registration business elsewhere! Oh, wait.

Incentives are shorthand for the relationship between benefits and costs, which attend every choice you make. The benefit of a choice you make is the value you expect to get from it. The cost is the value you expect to give up by making that choice. The larger your benefit is of making some choice relative to your cost, the stronger your incentive is to make it, so the more likely you will, and vice versa. Incentives are the reason you’re more likely to moon a stranger for $1,000 than for a nickel, forget to feed your goldfish as opposed to your son, or eat pie over poop—paleo dieters notwithstanding.

“Rules”—those pesky principles governing what’s permissible and what’s not, stipulating rewards or penalties for your compliance or noncompliance—affect your incentives. Rules can come from your government, employer, society, dominatrix. No matter their source, since they affect the benefits and costs of your choices, rules affect what you choose.

Suppose the government, in an effort to prevent this tour’s subversive message from getting out, began enforcing a new rule: “Anyone who takes the WTF?! tour will be summarily executed by officers of the law.” The incentives affecting your choice to be here would be very different than they are right now. Unless you’re extremely enlightened, you’d see the new cost of taking this tour as larger than the benefit, so you wouldn’t. But if, in an uncharacteristic moment of good judgment, the government announced that everyone who takes this tour will be exempt from paying taxes for the next decade, the museum would become much more crowded. Different rules, different incentives, hence different choices.

Rules have a cousin: “constraints.” Whereas rules govern what’s permissible, constraints govern what’s possible. You’d like to buy a new Ferrari, but your net worth is $5,000; your wealth is a constraint. You’d like to make a living as a carnival barker, but you’re a mute; your physiology is a constraint. You’d like to be able to read people’s minds, but the laws of physics won’t allow it; physics, a constraint.

The benefit of these things may be enormous, but the cost is infinite. Thus, constraints also affect your choices—by placing certain ones out of your reach.

The rules we create to incentivize people to make certain choices are themselves choices. Suppose that instead of trying to prevent you from taking this tour using the rule that I mentioned before, the government tried to do so with this one: “Anyone who takes the WTF?! tour will be summarily executed by invisible fairies.” How would this rule affect your choice to be here? It wouldn’t. The reason: presumably you don’t believe in invisible-fairy executioners.

The government might prefer to use this kind of rule to affect your incentives; it would certainly save the expense of hiring officers of the law to do the executing. Never mind the gore. But your belief or, rather, disbelief is a constraint that precludes the government from doing so.

What, then, can the government do? Choose an alternative kind of rule: one in which you’ll believe. It’s not as enticing as invisible fairies, but this kind of rule has the distinct advantage of actually deterring you from our delightful tour. Of course, any number of cases are possible: government may not exist (conspiracy theorists, hold on a minute), but people may believe that invisible fairies do. In such circumstances, the constraints are very different; hence, so too are the kinds of rules that are chosen to incentivize behavior. Get it?

The “WTF?!”-worthy practices you’re going to encounter as we make our way through the museum work the same way. They create rules that affect the benefits and costs of choices for the people who live under them, their incentives. And those rules reflect the existence of particular constraints in particular contexts. If, like detectives, we can sniff out the incentives, rules, and constraints inherent in every social practice, my dear Watsons, we’ll have seen the sense in it.

Once you get in the habit of thinking about things in this way, it’s easy. With your new tool, the remarkable, alien, and insane become mundane, familiar, and reasonable. Your bewilderment, astonishment, and perplexity become clarity, common sense, even glee.

The lessons you’ll learn dissecting the world’s weirdest practices on this tour will serve you long after you’ve walked through the exit, back into the weirdness of your everyday life.

Why does the Forest Service enlist the assistance of a cartoon bear to prevent you from committing arson? Why does American currency presumptuously declare, “In God You Trust”? Why does your uncle toss a coin to settle arguments with your aunt? Why does your religion have a say in your diet? And Santa Claus, of all “people,” why does he care whether you’re naughty or nice?

The answers to such questions are right in front of you—you just have to know how to see them. The power to do so is in the palm of your hands, so put that slip of paper in your pocket and follow me. I think you’re ready.

At the next stop, you’ll find our first exhibit. Try to stay with the group, but in case you get lost, a few directions: if you see a cycloptic dachshund, you haven’t gone far enough—turn the page again. If you see a bearded lady, you’ve gone too far—turn back a couple hundred.

You’re so quiet. Don’t be shy. Comments and questions are welcome. If you have something to say, just raise your hand. Oh, one more thing: if you’re the sensitive type, you may want to plug your ears. “WTF?!” is flying around in here like bugs at a BBQ.

![]()

2

Burn, Baby, Burn

I’m not exactly what you’d call a churchgoing man, though I was forced to attend Catholic mass and Sunday school growing up. My great aunt was a nun, so a march through the sacraments was mandatory too.

Despite my resistance, I had some good times with the religious part of my upbringing. There was the time I gave up going to mass for Lent (not the crowd pleaser I anticipated). And there was the time I suggested to my priest that we spice up communion by “bobbing for the Body”—fishing communion wafers out of a barrel of communion wine as one would bob for apples at a Halloween party (my parents got a phone call).

Less sacrilegiously, I enjoyed some of the biblical stories I heard—among my favorites, that of King Solomon. I’m sure you know this story; it’s one of the Bible’s greatest hits.

Two women come before the king disputing the maternity to a baby. Neither woman has evidence to show for her claim, and they want Solomon to decide their dispute.

Solomon proposes the following: he’ll cut the baby in half. Each woman will receive an equal share. This will be equitable, if a bit messy.

On the face of it, Solomon was a baby-hating madman. Or he was an idiot. Killing a baby and divvying up its corpse hardly seems like a reasonable response to a maternity dispute. The women who came to the king must’ve been shocked when he suggested his solution. The Bible doesn’t mention it, but I’m pretty sure both of them uttered “WTF?!” when Solomon presented his proposal.

You and I, on the other hand, know perfectly well what Solomon had in mind: the baby’s true mother would rather sacrifice her child’s custody than her child. Thus, the king inferred, she would turn down his proposal, allowing him to award the baby—in its entirety—to her. Which is exactly what happened. They didn’t call him “Solomon the Wise” for nothing.

We can learn a couple things from Solomon. First, judicial procedures that seem downright stupid may in fact be very wise. Second, when “ordinary” evidence is lacking, judicial officials may still be able to get to the bottom of things by creating clever rules—even ones that are based on a lie (“When maternity is in doubt, cut the child in half”). Clever rules manipulate people’s incentives, leading them to publicly reveal otherwise private information—information only they have about the truth—through the choices they make.

If you come over this way, you’ll see a metallic cauldron:

[The crowd shuffles down a few steps into a dim, stone-walled cellar.]

My goodness, it’s dark in here. Let me just . . .

[lights a torch dangling precariously from the wall]

Much better. As I was saying, what you see here is an ordeal cauldron. Ordeals were medieval European judicial officials’ way of deciding difficult criminal cases.

Those of you who’ve seen Monty Python and the Holy Grail might remember a scene involving ordeals. Some villagers are trying to decide if a woman is guilty of witchcraft. Their method is to compare her weight to that of a duck. In genuine ordeals, there was no duck, but there w...