![]()

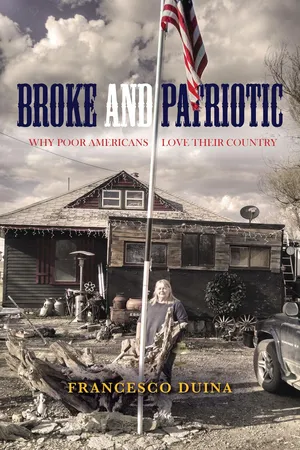

CHAPTER 1

A PEOPLE’S COUNTRY

Eddie,1 a fifty-six-year-old African American, lives in Birmingham, Alabama. Once a spelling-bee champion in school and “smart kid” who used to draw and love music, he now aspires to work in food services but earns less than one thousand dollars a month working at informal and irregular jobs, taking life day by day, and hoping—as his grandparents taught him long ago to do—that “maybe tomorrow will be better.” Though he served in the army for three years, he receives very few benefits from the government. He resides in the fifth most dangerous city in the United States, where the poverty rate is more than 30% and robberies, aggravated assaults, and arson attacks are commonplace.2 He knows that incomes for the people in the middle and lower classes in the country have been stagnating and believes that “the top percentage seems to be making all the money.” There are problems in the United States, for sure, and “no society is perfect . . . we have our dark shadows.” Still, despite all the difficulties in his life, he is convinced about one thing: America “is an exceptional country.” Indeed, as he puts it, America is “the last best hope for mankind on earth . . . the last best hope for countries on earth.”

Eddie is like millions of Americans. Many are poor and face serious adversity, and much in their lives is a daily struggle. They have access to very limited social services and support—partly a reflection of the fact that the majority of their compatriots, including those with very little, believe in the fairness of existing class differences. The odds that their children will enjoy a better life in the future are low. They also work very long hours while the gap between themselves and the rest of society, already considerable, continues to widen. On these and other dimensions their situation is lacking in both absolute and relative terms: by many measures, America’s poor are worse off than their counterparts in other advanced countries. To have no money in America is tough in itself, and tougher than being poor in most other rich societies.

And, like Eddie, these millions of impoverished Americans are highly patriotic. Given their predicaments, it could be reasonable to expect them to feel some dissatisfaction, if not resentment, toward their country. With the American Dream eluding them and little in their lives suggesting that things will improve, the American poor—understood in this book as those belonging to the most economically disadvantaged class in society—could understandably be critical of the society in which they live. In some respects, they certainly are. Many believe that, in a practical sense, a lot needs fixing—a sense of disgruntlement that the likes of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders tapped into during their 2016 presidential campaigns.

But their fundamental belief in the country remains unshaken and, indeed, by any measure stunningly strong: 80%–90% of America’s poor (and even more, depending on how exactly we define the “poor” and measure their “patriotism”) hold the United States in high esteem. They are proud of their nation, believe in the greatness and superiority of the United States, and would rather be citizens of America than of any other country in the world. In fact, their patriotism—defined in this book as the opinion that their country is fundamentally better than other countries—is extraordinary. They are more patriotic than the poor in almost all other advanced countries in the world, even though the latter are in many ways better off than they are. In the United States their patriotism exceeds in many instances the patriotism of working-class, middle-class, and upper-class Americans. So, although America’s least well-off have reasons not to love their country, they hold it dear to their hearts and in many ways idealize it.

The sentiment is widespread—cutting across race, gender, political, and religious lines. Patriotism is high among impoverished white, black, and other nonwhite Americans. It is high among poor men and women, liberals and conservatives, religious believers and nonbelievers. While there are certainly variations across regions of the country (in the Middle Atlantic region, for instance, it is less widespread), their patriotism is high in absolute terms in every region of the country. It is also a resilient sort of patriotism: among all classes in the United States, the patriotism of Americans living in poverty has been affected the least by the economic crisis of 2008–2009, and by some measures it has actually increased.

This book is about Americans like Eddie and their patriotic views. It is about impoverished Americans and their intense love of their country. Why are America’s poor so patriotic? Specifically, what attributes do they ascribe to the United States? How do they think those attributes shape their lives? What are the limitations that they see in other countries that make the United States superior to those countries? And, crucially, how do these Americans reconcile—if they in fact do—their own difficult situation with their positive view of the country? This is a book about what sociologists would call the “narratives” of patriotism among the poor: the conceptual threads, images, stories, and visions that the economically worst-off Americans articulate about their country. It is about their stories and perspectives. It is an effort to investigate, hear, and understand firsthand the logic and reasoning of this particular segment of the American population—a segment that our wealthy and extremely powerful society seems to have forgotten in many ways or to have left behind with little consideration.

Why should we try to understand the patriotism of America’s least well-off? Two reasons concern the country’s social and political stability. First, the maintenance of the social order depends on widespread trust and positive feelings toward the public sphere.3 The same can be said for the institutions and practices of successful democratic governance: they, too, require trust and the positive disposition of citizens.4 High levels of patriotism certainly promote (and reflect) such trust and positive feelings. The patriotism of America’s poor contributes to social cohesion and, thus, the peaceful and daily unfolding of life in society. Put in perhaps more dramatic terms, their patriotism may keep them content enough not to seek a major overhaul of society—with implications for the agendas of political parties, the direction of policies, and the continued availability of labor to provide basic services.5 There are certainly concerns in the United States and elsewhere about widespread discontent among America’s most economically challenged people and what this could mean for social stability: “Why aren’t the poor storming the barricades?” recently asked the Economist when reflecting on inequality in America.6 “Why don’t the poor rise up?” wondered Thomas Edsall in his regular column in the New York Times.7 And in the words of former US secretary of labor Robert Reich, “Our incomes are declining, the ranks of the poor are swelling, and almost all the new wealth goes to the wealthiest. So why aren’t Americans rebelling against the system?”8 The patriotism of the poor is likely part of the answer.

At the same time, rather than act as a force for stability, that same patriotism could be leveraged by populist movements looking to bring major changes to society. The recent rise of far-right parties in countries such as France, Austria, and Denmark offers one example of how that might happen. Their agendas, with “a focus on national identity,” have included the rejection of international forums of cooperation, threats of protectionism, and xenophobic initiatives.9 The patriotism of the poor need not necessarily be leveraged in this way, of course; yet the potential for populist appropriations of various kinds is always there. For many observers, the 2016 presidential elections in the United States featured precisely such rhetoric—in particular, Donald Trump’s campaign and its calls to those who have been left behind for big changes in the name of “making America great again.” This is the second reason why we would do well to understand the mind-sets of America’s least-well-off citizens.

Geopolitical considerations should also encourage such an investigation. America’s poor contribute greatly to its military, which is the most powerful the world has ever seen and constitutes a fundamental pillar of American society. As has been the case throughout the decades—consider that 80% of soldiers serving in Vietnam had a high school degree or less10—the majority of American military personnel these days come from the lower and middle economic classes, with only 13%, for instance, having some college education.11 Much less than 10% have a college degree.12 To be sure, in a controversial study in 2008 the Heritage Foundation reported that Americans from poorer neighborhoods (those with household income levels in the lower two quintiles) appeared to be underrepresented in the 2006 and 2007 recruiting years.13 But many other analyses show otherwise: large numbers of recruits reportedly do come from poor neighborhoods (those with income levels in the second- and third-lowest deciles),14 and the military has struggled to meet its target goal of recruits with high school diplomas, with just above 70% of recruits (rather than the desired 90%) in 2007, for instance, actually having those diplomas.15 In addition, base pay for enlisted military members has for decades de facto relegated many military families to the ranks of the poor or near poor.16 The military greatly depends, then, on Americans with limited means to fill its ranks. This need would not be met if America’s worst-off citizens did not have at least some patriotic feelings toward their country. What is the nature of those feelings?

Relatedly, on the international stage, where American power remains unmatched, a sense of national identity, along with a sense of purpose and national unity, shapes how the United States acts in the world and is perceived by others. Surveys and research data alike consistently show over time that much of the world still admires the United States and the values—freedom, individual rights, the pursuit of personal happiness, optimism, equality, and opportunities for all—for which it stands.17 Such international admiration of the United States is predicated, in part, on the perception that Americans stand united, strong, and committed to those ideals. The assumption is justified, since most Americans do appear to subscribe to those values, as recent research and polls by the Pew Research Center and the World Values Survey on optimism, the pursuit of happiness, and freedom show.18 Americans of all stripes need to believe in America’s ideals if the country is to project itself successfully onto the world as a shining city on a hill. Again, we should have a clear understanding of those beliefs.

Two more important reasons should compel us to better grasp the patriotism of America’s least well-off. Being poor affects a large percentage of the American population. The US Census Bureau estimated in 2014 that around 15% of Americans (forty-seven million) live below the poverty line.19 Many are children: UNICEF reported in 2012 that the United States has the second-highest rate of child poverty among the world’s developed countries.20 Their situation is at best stagnant and in fact probably worsening: household income for those in the bottom quintile of incomes, when adjusted for inflation, dropped by more than 15% from 2000 to 2014.21 Indeed, inequality in America is among the highest in the world, is persistent, and has widened steadily over the decades.22 A 2015 Pew Research Center Report showed that the middle class is shrinking.23 Politicians, the mass media, academics, and many members of the public have accordingly called for a deeper understanding of the poor of America: the problems they face, the values they hold, their aspirations, and their preferences.24 Understanding their patriotism seems an essential step in this regard.

Finally, we should recognize that the patriotism of the American poor contributes directly to the country’s understanding of its essential qualities. Modern nation-states depend on shared understandings among citizens of “belonging” and of being part of “imagined” communities.25 National identities, in other words, are not simply given but are instead socially constructed. With this in mind, sociologists have described American national identity as consisting, in part, of the celebration of individualism over the supremacy of the collective (as in communism) or over the imposition of preestablished notions of the good or righteous life (as in theocratic governments).26 In the United States, people can do as they wish, provided that their actions do not infringe on the rights and well-being of others. This combination of beliefs is in turn matched by an unusual sense of exceptionalism, by a conviction that America’s celebration of individual self-determination is unique and unprecedented in history, and that, as a result, America is the greatest nation on earth.27 To work, such a vision of what it means to be American requires the participation of most members of society regardless of rank or place in the social system. It is, perhaps counterintuitively, a collective endeavor. The least well-off are therefore an indispensable part of America and its sense of self.

Much depends, then, on the patriotism of the American poor. Thus, it is rather surprising that few researchers have asked people who suffer from considerable financial hardships why they feel so positively about their country. There certainly is considerable research on American patriotism in general and on the patriotism of categories of people such as women, African Americans, or Native Americans. There is also some research on the principles of group cohesion and why disadvantaged members can at times feel very attached to a group. These works can offer us some potentially useful ideas about the patriotism of the American poor. Yet these remain only untested insights, since they do not focus on America’s poor as a specific group worthy of study and investigation. We simply do not know much about the extent and logic of their belief in their country’s greatness. Thus, this book tackles two questions: Why do America’s poor think so highly of their country? How do they reconcile their economic difficulties with their appreciation of their country?

The best way to answer these two questions is to hear the voices and reflections of America’s poor themselves. Eager to do so, I conducted in-depth, face-to-face interviews (each lasting between thirty and sixty minutes) during 2015 and 2016 with sixty-three low-income patriotic Americans in two areas of the United States that are arguably hotbeds of patriotism among the poor: Alabama and Montana. These interviews yielded nearly nine hundred pages of single-spaced transcribed conversation texts. I discuss in more detail in Chapter 3 the methodology I followed for selecting the sites (Birmingham and Vernon in Alabama, and Billings and Harlowton in Montana), identifying and selecting the interviewees, conducting the interviews, and analyzing the transcripts. I should nonetheless state here that the respondents included people living in cities and rural areas and were of different races, genders, political and religious orientations, and histories of military service. Importantly, my objective going into the interviews was not to generalize about any particular subgroup of America’s poor: in-depth interviewing necessarily limits the sample size of respondents and therefore does not allow for that sort of analysis. Rather, the aim was to have exposure to as broad a number of persp...