![]()

1 GROWTH OF THE STATE UNDER MUBARAK

Follow the Revenue Trail

THIS CHAPTER AIMS to define the main parameters of the semi-rentier state in Egypt and to trace and analyze the course of revenues and expenditures in Egypt since the outset of the 1980s. The purpose is to answer two questions.

First, what factors account for the fluctuations in revenues and expenditures? The theory we propose here is that the level of state revenues sets the pace of public spending. When revenues increase, so do state expenditures, and vice versa. Official economic policy, be it interventionist or laissez-faire, has little effect on the volume of public spending. Its rise or fall is not the result of a decision.

Second, what factors determine the volume of state revenues? The Egyptian state derives much of its income from petroleum sales, Suez Canal fees, and foreign aid. These are essentially rentier revenues, and they have driven national fiscal policy since the 1970s. Without understanding the fluctuations in these revenues, it is impossible to explain the transformations in economic policy.

MUBARAK ANNOUNCES A NEW ECONOMIC POLICY

“Prosperity is at hand,” Egyptians were told during the 1970s. Toward the end of that decade, President Anwar Sadat promised that 1980 would be the “year of prosperity,” and in September 1980, the minister of the economy proclaimed that the era of prosperity had begun. The upbeat tones faded quickly following the assassination of Sadat on 6 October 1981.

On 6 November 1981, several weeks after President Hosni Mubarak came to power, the editor-in-chief of Al-Ahram confirmed that the economic crisis was severe. His editorial ushered in a new official rhetoric on the economy that would contrast strikingly with the rhetoric that prevailed throughout the 1970s. The new official discourse was inaugurated in an economic conference that Mubarak convened in February 1982. In his opening address to the conference, cited in Al-Ahram Al-Iqtisadi on 22 February 1982, the president explained that the purpose of the conference was not to make general recommendations, but rather to assess the state of the economy with an eye to formulating an action plan. The conference’s general conclusion, as laid out in the closing statement, was that the government would revert to central economic and social planning and steer the Open Door policy1 toward production. As the secretary-general of the conference said in this statement, the process of liberalization had to continue, but there also had to be a drive to reduce consumption and increase production. He added that the government was keen to propel the private sector toward the productive sectors and would take all necessary measures to achieve this.

The new economic orientation triggered heated debate in the government and in the opposition press over the value of the Open Door policy. A major forum was the state-owned magazine Al-Ahram Al-Iqtisadi, which opened its pages to such left-wing economists as Fouad Mursi and Ramzi Zaki. In their opinion, the policy was a failure. Among the many reasons they cited, the most significant was that the policy generated consumerist tendencies and favored increased importation over strengthening the productive sectors, especially industrial production. Economic growth in the 1970s, they maintained, had been purely a consequence of the influx of rentier revenues, primarily from the Suez Canal, petroleum, and foreign aid. Egyptian capitalists, meanwhile, focused their energies on speculation and investment in quick-profit fields such as consumer imports and real estate construction. This entrepreneurial class made up the “parasitic sector” of Egyptian capitalism. In Mursi’s and Zaki’s opinion, the solution was to encourage nationalist capitalism by reducing imports (by increasing protective customs taxes) and, of course, by revitalizing the role of the state in production.

The opposing camp of right-wing economists took up the defense. However, even as they continued to advocate the Open Door policy out of principle, they had to acknowledge that it had promoted growth in the trade and financial sectors over industrial growth. They further admitted that it had encouraged a flourishing opportunistic entrepreneurial class that had come to form “actual power centers,” as former Prime Minister Abdel Aziz Higazi was cited as saying, according to Al-Ahram Al-Iqtisadi on 26 April 1982. Higazi had been selected by President Sadat to head the government during the transition to a market economy.

The Egyptian intelligentsia concerned with economic affairs was thus unanimous in the opinion that the Open Door policy had to be reassessed and rectified. The difference between the right and left was over how to rectify it and to what degree.

It was not long before left-wing economists came to feel that all the work they had put into studies and preparations for the economic conference hosted by the new president had gone to waste. The president heeded none of the recommendations of the conference or, at best, adopted only the easy parts. But as partial as the regime’s implementation of these recommendations was, the difference between its economic rhetoric and that of the previous regime was total. Under Mubarak, criticism of the Open Door policy was not only officially condoned but also actively encouraged. In addition, the government sought to boost both private and public sector industry. Toward this end it raised protective import barriers, lowered the interest rate on industrial investment loans, and, significantly, reduced taxes on industrial profits to 32 percent at a time when the capital gains tax in other commercial sectors was 40 percent.2

These measures did, in fact, help stimulate growth in the industrial sector. The government boosted spending on industrial expansion in the private sector, and a greater share of private sector investment went into industrial activities, increasing from 15.9 percent in 1981 to 34.7 percent in 1990 and 45.9 percent in 1995.3 The share of industry (excluding the petroleum sector) in the GDP increased from 13.5 percent in 1980–81 to 18.1 percent in 1990–91.4 The new emphasis tangibly manifested itself in the rise of such industrial cities as The Tenth of Ramadan and Six October. It was also reflected in the decision on the part of a number of import magnates of the 1970s to turn to joint production enterprises with foreign investors. For example, Mahmoud Al-Arabi shifted from importing Toshiba appliances to assembling them and manufacturing some of their parts, and the Abaza family turned from importing Peugeots to assembling them and manufacturing 40 percent of their components. These are two notable instances out of many.5

Most of the growth of private and public industry in the 1980s, especially in clothing and automobile assembly and manufacture, was heavily contingent upon customs protection, which is to say upon government intervention aimed at keeping prices of imported goods higher than prices of their Egyptian counterparts. This gave both state and private capitalism the opportunity to dominate the local market and set prices that often exceeded those that prevailed in other countries at Egypt’s level of economic development.

EXPLAINING THE SHIFT IN ECONOMIC POLICY: FOLLOW THE REVENUE TRAIL

A common way for new presidents to establish their legitimacy is to point to the economic problems bequeathed by their predecessors and to disparage the policies that created them. It was only natural, therefore, that Mubarak would begin his reign with the refrain of severe economic crisis. Most analysts in Egypt have tended to dismiss that refrain as little more than propaganda. Yet, the new official rhetoric in the early 1980s reflected a change from the Sadat era, albeit not as radical as Sadat’s about-face from the political orientation of the Gamal Abdel Nasser era (1956–70). Upon coming to power, Mubarak, like Sadat before him, applied himself to the task that any new regime has to undertake if it is not going to rely solely upon the instruments of violence and terror. That task was to build his own sociopolitical base. To do this, Mubarak had to clip the wings of powerful business magnates associated with the Sadat era, such as Rashad Osman and Esmat Al-Sadat, so as to clear the way for a new set of business magnates entirely loyal to him. The other social class that the Mubarak regime could easily court consisted of government employees. They were deeply resentful of Sadat’s economic policies, which had cast them down from the elitist status they had enjoyed under Nasser to a much lower rung on the social ladder. The new official discourse about the return to central economic planning and the major economic role of the state was intended to reassure and win over this segment of the public.

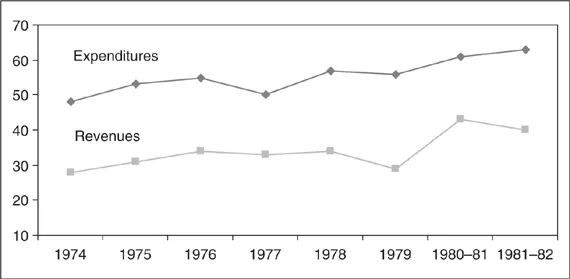

Nevertheless, the shift in economic policy stemmed from more than the exigencies of building the legitimacy of the new president. Mubarak would not have partially reverted to economic planning had it not been for the growth in state revenues, a trend that began in the mid-1970s (see Figure 1.1).

The growth of the Egyptian state apparatus was the irony of the decade of the 1970s. While the official discourse emphasized the conversion to a market economy, the centrally steered economy burgeoned. Undoubtedly, the rise of a new and very conspicuous class of capitalist entrepreneurs and a very ostentatious nouveau riche gave the impression that the private sector was taking over an increasing share of the resources from the public sector. The fact is that this did not occur during the 1970s. As more money flowed into the pockets of the rising entrepreneurial class and a segment of the middle and professional classes, state-controlled revenue sources poured even more into the coffers of the national treasury. Consequently, government control over the nation’s resources increased. According to a World Bank study, public spending soared from 48 percent of the GDP in 1974 to 62 percent in 1981.6

Figure 1.1. Public Revenues and Expenditures as a Percentage of GDP in Egypt, 1974–82

SOURCE: Sadiq Ahmed, Public Finance in Egypt. Washington, DC: World Bank, 1984.

Despite the influx of revenues, the regime was still inclined to borrow and to demand more aid from abroad. One can not help but remark how similar this situation was to the era of the Khedive Ismail a century earlier. Then it was revenues from cotton that poured into the state’s coffer as the extravagant khedive plunged headlong into debt. In the 1870s, the Egyptian debt crisis led to the system of Dual Control, whereby French and British commissioners took over the management of the Egyptian economy; in the 1970s, Egypt’s creditors pressured the government into concluding an economic reform agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Signed in 1977, the agreement obliged Egypt to reduce the national deficit and reduce government spending. President Sadat complied; one of his first actions was to lift subsidies on essential foodstuffs such as bread, flour, oil, sugar, and rice. Egyptians awoke on the morning of 18 January 1977 to discover that the prices of the staples upon which millions of poor and low-income families depend had suddenly doubled. The popular reaction was instantaneous and powerful. Mass protests and violent rioting lasted two full days before finally being suppressed by the military and police. About a hundred people died, and several hundred more were wounded in the confrontation between security forces and demonstrators. The Bread Riots, as this uprising came to be known, marked the first time since the milit...