![]()

1

IMPACT ENTERPRISE FOR THE BASE OF THE PYRAMID

The ideas are powerful: Creating enterprises with impact. Using the power of market-based approaches to address social issues. Alleviating poverty through enterprise. Creating value with the base of the pyramid. And the stories that grow out of those ideas are compelling: Entrepreneurs, company leaders, nonprofit managers, and development community professionals are talking and writing about how well their enterprises are doing and their profound impacts on the base of the pyramid (BoP), which I define as the 4 billion or so people who primarily live or transact in informal markets in the developing world and have an annual per capita income of less than $3,000.1

Not surprisingly, given this wealth of ideas and stories, the bookshelves are starting to fill with striking titles like Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid, The Business Solution to Poverty, Business Solutions for the Global Poor, and Capitalism at the Crossroads. Terrific books, all—replete with powerful ideas and filled with great stories of success.2 They show us what is possible. They are motivational. They are about promise and potential. As C. K. Prahalad, arguably the intellectual pioneer in seeing the business opportunity in the base of the pyramid, wrote about the aspirations he had for his own book: “Does it change the conversation? Does it show opportunity? Does it lead to action?”3

These books have found a receptive audience. The past decade has seen a surge in the number of impact enterprises for the BoP, the provision by these enterprises of high-quality goods and services to the poor and vulnerable, and investors’ growing willingness to support these efforts.

All in all, these are exciting times for those who believe that business can play a key role in addressing social issues, especially alleviating poverty, and who are interested in exploring and helping to realize the promise of impact enterprises for the BoP.

But something is missing. Hundreds of ventures aimed at serving the BoP have been launched, but comparatively few have achieved significant scale.4 Either they have closed up shop and gone home, or they suffer from “pilotitis”—in other words, they remain small and highly dependent on continued financial support to maintain the piloting activities. This collective failure to thrive underscores a key point: Developing sustainable, scalable enterprises is a challenge in any context, and it is especially difficult in BoP markets.

Individually, we have gained much experience. But collectively, in confronting the challenges of the BoP market, we still have yet to share and build from these experiences in a way that productively moves the entire domain forward. For example, a colleague who was visiting my office not long ago is an experienced and successful entrepreneur in the technology industry. He had become engaged in BoP impact enterprise development in India several years ago, and I hadn’t heard from him in a while. The first thing I noticed on this visit was that he had become far more humble.

“We thought we knew what we were doing,” he said, in a forlorn voice, “but we have made all the mistakes in the book.” He had believed that his years as a successful top-of-the-pyramid entrepreneur would translate smoothly into the BoP context. It didn’t work out that way. As he told me what had gone wrong, I found myself thinking: Why did he have to go through the same pains that many others have already suffered?

Too many entrepreneurs, enterprise leaders, and development community professionals fall into this trap—a trap of their own making. They assume that these are still uncharted waters and we don’t know all that much about successfully developing impact enterprises for the BoP. Because they persist in starting from scratch, they continue to make the same mistakes.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Our collective learnings can offer insight into what works and what doesn’t. That’s what was on my mind when I sat down to write this book: a road map—a set of tools, frameworks, and approaches—for contributing to success in this exciting and challenging domain.

I readily admit that this is an audacious goal. Setting out to create a tool kit that can help enhance the success of business in BoP markets, with the ultimate goal of addressing a major social issue that challenges the very fabric of today’s society, is a bold undertaking. The relentless poverty that the BoP faces is a large and looming threat to any vision of a more equitable and peaceful world.

Building sustainable, scalable enterprises in BoP markets won’t be easy. Perhaps more than anything else, embarking on this journey will require embracing new mind-sets, new strategies, and new approaches to collaboration. As much as we might like to, we can’t donate our way out of poverty. Business has a role to play, but business also can’t do it alone—and that means that incremental additions to what we know, and incremental adjustments to how we do things, are not likely to yield the transformational change required. We need a much deeper understanding of what works and what doesn’t when it comes to building what I will call impact enterprises for the BoP.5

WHY BRING TOGETHER BUSINESS AND DEVELOPMENT?

New knowledge and new ways of collaborating are needed. Fortunately, enterprise leaders and development professionals alike are excited about pursuing market-based opportunities with the prospect of achieving positive social impact. It’s worth exploring why they are so excited about this promise and this potential.

Let’s start with the business perspective. The 4 billion people comprising the BoP constitute a huge socioeconomic sector that lacks access to a multitude of goods and services, and at the same time faces constraints when trying to bring its own production to market—things that well-designed businesses could provide. At the same time, as economic growth slows in the developed world, the BoP represents perhaps the world’s last great untapped market, so when it comes to future growth opportunities, the BoP is increasingly seen as an exciting market worthy of deeper consideration.

The cell phone phenomenon hints at this opportunity. There has been astonishing growth in cell phone subscribers in the developing world, whose numbers increased from 370,000 to 16.8 million in only five years. One telecom company, Celtel, started as a shaky venture in 1998, operating in the Democratic Republic of Congo, with a population of 55 million and only 3,000 phones. Seven years later, when it was acquired by a U.S. company for $3.4 billion, Celtel was operating in fifteen African countries, with licenses covering more than 30 percent of the continent.6 It is hard to travel anywhere in the developing world, urban or rural, and not see people across all socioeconomic segments carrying cell phones. First-time visitors to BoP markets are prone to marvel at how many people have one.

Total annual household income in BoP markets is estimated at something like $5 trillion, or about $1.3 trillion when adjusted for in purchasing power parity.7 Yes, the average size of transactions is relatively small, but their aggregate number is extremely large. Furthermore, the BoP holds something like $9 trillion in unregistered (or hidden) assets, an amount approximately equivalent to the total value of all companies listed on the twenty most developed countries’ main stock exchanges.8

In addition, the opportunity for learning and growth to flow upmarket should not be underestimated. General Electric, for one, has made the argument for the value of reverse innovation.9 Although many top-of-the-pyramid models don’t work well in BoP markets, it’s increasingly apparent that BoP innovations may revolutionize aspects of top-of-the-pyramid business, perhaps beginning in the environmental and health realms.10

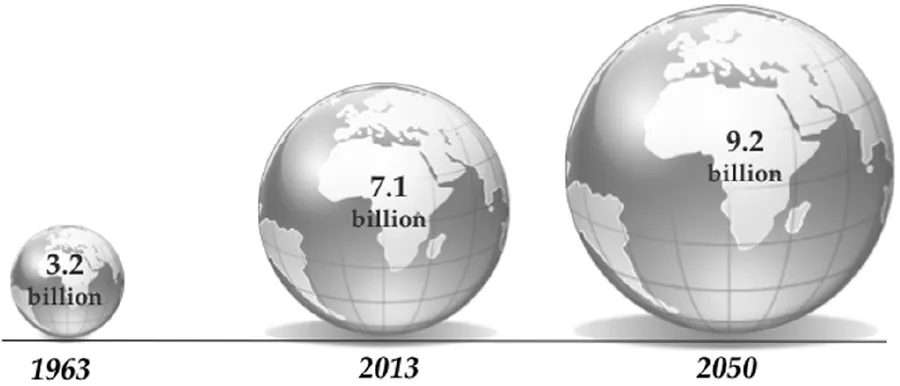

Demographics are also an argument for bringing together business and the BoP. The planet is getting more and more crowded. The world’s population will increase by another 2 to 3 billion people in the next thirty years, and most of those new additions will be part of the BoP.11 The magnitude of this growth in human population can be hard to comprehend. A way that I have found helpful is to consider the human population growth in the span of one lifetime, as illustrated in Figure 1.1. Imagine someone born in 1963, when world population was about 3.2 billion. By the time he or she turned fifty, the population on the planet had more than doubled: an increase of nearly 4 billion people in that half-century. Assuming this person lives for eighty-seven years, the population during his or her lifetime will have nearly tripled, with an additional 6 billion people having been added to the human head count in a single lifetime,.12 And again, most of this growth will likely have occurred in the BoP socioeconomic segment.

As the Swedish multinational Tetra Pak and other companies have observed, some of those in the BoP segment may well move up the pyramid over time, thereby becoming even more attractive customers to these companies.13 Of course, as some people move up the economic pyramid, others may suffer a reversal of fortune and fall back. But the larger point remains: The business opportunity is substantial now, and it will only get bigger.

FIGURE 1.1 Population growth within one lifetime

The development community has to deal with the same growth numbers but with a different framing. The development challenge is already intimidating, and it will become more daunting. Since World War II, development agencies and donors across the globe have spent billion of dollars to alleviate poverty and improve the lives of people in developing nations. Certainly some of these efforts have led to important successes. The emerging consensus, however, is that despite their massive scale and their long histories, these efforts alone haven’t done enough.14 As Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto has argued, billions of people still primarily transact in informal markets and lack access to the benefits of globalization.15

Facing these challenges, the development community is increasingly seeking new approaches to carrying out their core missions of improving the social and economic well-being of the BoP. During the past half-century, business was often seen as part of the problem rather than part of the solution. As a result, philanthropic efforts, rather than market-based approaches, were the dominant approach to alleviating poverty in the developing world.

In recent years, however, a wide variety of players, ranging from government agencies to nongovernmental organization (NGO) leaders to foundations, have made concerted efforts to encourage more enterprise-oriented activities in BoP markets.16 The private sector is seen a potentially valuable partner, impact investing has taken off, social entrepreneurs are supported across the globe, and the development community—with its substantial resources—has increasingly embraced impact enterprise as a new and complementary poverty alleviation strategy.17

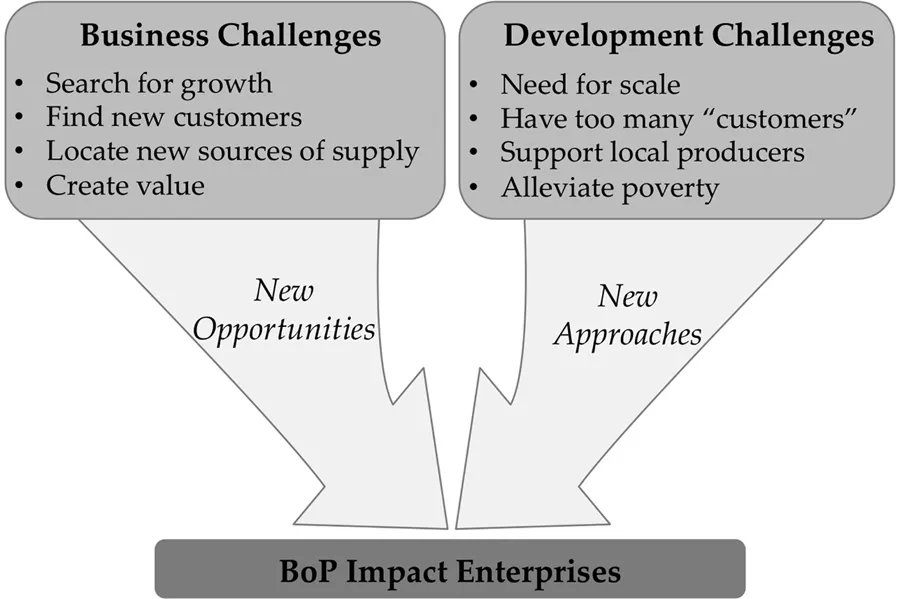

In short, we see a convergence of agendas, as suggested in Figure 1.2. The development community wants new approaches for scaling impact at the same time that the business community wants new opportunities for future growth. Given their increasing alignment and complementary skills and resources, working together seems to offer the best opportunity to facilitate successful BoP impact enterprise development.

FIGURE 1.2 Collaborating to build BoP impact enterprises

DEFINING A BOP IMPACT ENTERPRISE

Collectively we need an explicit definition of a BoP impact enterprise because the cast of characters involved is large, growing, and is sometimes quite passionate about what they seek to achieve. Therefore, too broad a definition will lead to confusion. Distilling this dialogue down to its essentials can facilitate more robust and productive conversations. With that in mind, here is my definition of impact enterprise for the BoP: A BoP impact enterprise is one that operates in the underdeveloped market environments in which the BoP transacts, seeks financial sustainability, plans for scalability within and across markets, and actively manages toward producing significant net positive changes along multiple dimensions of well-being across the BoP, their communities, and the broader environment.18

This definition recognizes that BoP impact enterprises can be an individual enterprise or an interconnected network of ventures, such as those found in franchise models and value chains. It also emphasizes the importance of seeking financial sustainability and endorses the idea of a financial return on investments made. Of course, this expected return—both the amount and the timing—can vary according to the specific goals of the entrepreneurs, investors, and other stakeholders of the enterprise. The point is that the enterprise must seek (and hopefully, achieve) a financial return that satisfies its owners and enables long-term financial sustainability.

The definition also recognizes that achieving impact requires enterprises to reach scale, which means they must grow beyond serving local consumers in a local market. This growth can be the result of serving more buyers and sellers with existing products or services offerings, providing existing buyers and sellers wit...