![]() Part I Visions of National Renewal

Part I Visions of National Renewal![]()

1

Cultural Affairs under Vichy

As in each painful chapter in their history, the French people must rediscover their identity, in the aftermath of defeat, within defeat itself. . . . We must end the delusion that our neighbors will bring happiness, counting on others to escape a difficult situation. . . . We must rebuild for ourselves this France, which will become for us as it was for our ancestors, “Land of France, my sweet country.”

—Fernand Lemoine, La Nouvelle Revue Française, 1 July 1941

The soldier should take upon himself a personal duty, despite the harshness of war and contrary to all the powers of destruction, to preserve the meaningful, the beautiful, and the exemplary created by history as “the Great One”—Goethe—had in mind when he crafted just the right words for this situation:

Whoever protects and preserves

The many splendors of the world,

Dissolved war and conflict.

Secured the most noble destiny.

Protect and preserve—that is the German task.

—Franz Albrecht Medicus, Schlösser in Frankreich, guidebook on

French chateaux for German soldiers published in Paris, 1944

DURING THE SIX-WEEK CAMPAIGN AGAINST FRANCE, from the launching of Hitler’s invasion on 10 May 1940, to the signing of the armistice on 22 June, an estimated 6 million panicked civilians fled northern France, desperate to reach safer ground. They loaded up cars, carts, and bicycles with their most cherished possessions or set out on foot with all they could carry. They became refugees in their own country, uncertain how long they would be away from home. With healthy men of fighting age at the front, mothers bravely gathered their children and packed food for the next meal or two. The refugees jammed the roads outside Paris, competing for space with French military vehicles that were pushing against the human tide, toward the front. They were beset by fear, uncertainty, and periodic strafing from the Luftwaffe, whose brutality already had been immortalized in Picasso’s Guernica. Some of the refugees planned to join friends and relatives in designated locations; others had no specific destination—just somewhere farther south.

On 10 June, with German forces encroaching on Paris, the French government joined the civilian exodus. Cabinet members regrouped on 14 June in the city of Bordeaux on the southern Atlantic coast. In accordance with the Third Republic’s 1875 constitution, on 16 June Premier Paul Reynaud nominated eighty-four-year-old Marshal Philippe Pétain to form a new government that would negotiate peace terms. President Albert Lebrun accepted the nomination, and the following day, Pétain informed the French people by radio that their government had surrendered.

The devastation of military defeat, within a matter of weeks, was compounded by humiliating peace terms. Hitler delighted in the symbolism of signing the armistice in the exact location as the 1918 armistice, in the Rethondes clearing outside Combiègne. The earlier armistice had been signed inside the private railway car of Marshal Foch, the French general who had led Allied forces against Germany and its allies in the Central Powers. A symbol of French victory, Foch’s railway car had become a tourist attraction between the world wars, a sign that France had avenged the Prussian defeat of 1870. Hitler, a master of symbols himself, reversed the referents of victor and vanquished, transforming Foch’s railway car into a sign of German resurgence.1

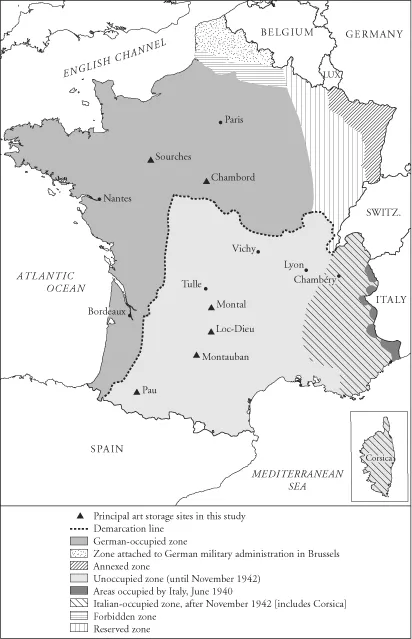

The 1940 armistice agreement divided France into several administrative zones. The Third Reich annexed two French departments, Alsace and La Moselle, incorporating them into its own administration. The German military command in Brussels absorbed the Nord and Pas-de-Calais departments, and northeastern France was divided into two regions: the “forbidden” zone, extending north of the Somme and Aisne rivers, and the “reserved” zone, covering eight French administrative departments northeast of the Meuse, Aisne, and Saône rivers. These two special zones portended further possible annexations of what the Reich considered “Germanic’’ departments. The main German-occupied zone extended from the English Channel to the Loire River and jutted southwest to the Spanish border, thus incorporating the country’s entire Atlantic seaboard. The unoccupied or so-called free zone made up two-fifths of the national territory, in the resource-deprived central and southeastern regions.

The Partition of France, 1940–1944

With the city of Bordeaux now in the occupied zone, French officials sought out another temporary headquarters. They settled in the spa town of Vichy in central France, forever linking that city to the wartime regime and the darkest period in modern French history. A popular vacation spot for those seeking the therapeutic benefits of natural hot springs, the town of Vichy offered, above all, an array of hotels that functionaries quickly converted into offices. Over the next four years, the city’s population grew from 30,000 to 130,000 because of the influx of government officials, who adapted to the inconvenience of cramped quarters and restricted telephone service.

As the fighting ceased in northern France and civilian refugees worked their way back home, Pétain and his government continued to operate in a state of dislocation. Article three of the armistice agreement provided for the government’s return to Paris, and Pétain hoped to establish his headquarters at the nearby Versailles palace. It was a rather appropriate idea, as one of his aides would later quip that the Marshal ended up consolidating more power than Louis XIV.2 Yet Versailles also had some drawbacks. An adviser pointed out that the palace was too isolated and evoked negative images of the Old Regime and Adolphe Thiers’s headquarters in the early Third Republic following the Prussian victory. This aide had another palace in mind for Pétain—the Louvre.

In a note to Pétain, the adviser explained that the Marshal’s battle against enemies—both foreign and domestic—would require the use of les armes morales (moral weapons); the Louvre was just “this kind of weapon.” The palace was the “political heart of Paris,” near the city’s “spiritual heart beating on the Ile de la Cité,” a reference to Notre Dame cathedral. The Louvre was familiar to all Parisians, “the perfect museum, the only one that French people know” and “the most majestic urban palace in the world.” If Pétain were living at the Louvre, Parisians would feel that he was “close to them, in their home.”3 Pétain’s presence at the Louvre would show a certain amount of noble self-sacrifice. The French people would recognize the “discomfort” and “spiritual value” of living in the museum, as opposed to the heady opulence of Versailles. They would know that “something new really was happening,” that France would be “remade at the Louvre as it was by the Capetians and Richelieu,” referring to the consolidation of the French monarchy in medieval and early modern times, before the construction of Versailles. On a more practical level, Pétain’s presence in the Louvre would also help “protect the treasures of our patrimoine national against certain appetites,” an allusion to the Nazi art looting that was already under way. As the Louvre’s newest resident, the Marshal would thus serve as the ultimate protector of the French people and their artistic treasures.4

In the end, Hitler did not allow the government to return to Paris, and Pétain maintained his headquarters in Vichy. But the proposal illustrates one of many possible interpretations of the palace’s symbolic power beyond its functional use as a public museum. It is a vision of the Louvre as an embodiment of the nation, an instrument for unifying the French people through their cultural heritage. Over the next four years, Pétain would sign into law several key measures to protect French national treasures, thus also protecting a certain traditional idea of France.

The government that later would be known as “the Vichy regime” thus formed in the midst of crisis, dislocation, and humiliating defeat to France’s modern archenemy. The transfer of power to Pétain was entirely legal within the Third Republic’s constitutional framework. When Pétain became président du conseil (premier) on 16 June, the Republic’s two-person executive endured, with Lebrun continuing to serve as president. However, Pétain wished to dispel fears of a military coup and acknowledged his need for assistance managing the government. Veteran politician Pierre Laval thus earned the position of vice-président du conseil (deputy premier) on 27 June.

Laval felt quite at home in Vichy, as he was born in the nearby village of Châteldon and still held property there. The son of an innkeeperbutcher, he had followed the path of other ambitious young men from the provinces and pursued a legal career in Paris. After establishing a law practice in the capital, he was elected to parliament as a socialist in 1914. Over the next twenty years, the practice prospered, his wealth grew, and his political views shifted from left to right. He held a variety of political positions in the 1930s—as parliament member, mayor of Aubervillers, foreign minister, and premier. Following the 1940 defeat, at the age of fifty-six, he was eager to draw on his extensive political experience and serve in Pétain’s government.

Although Hitler had forced the French to accept defeat and occupation, he did not coerce them into creating a new regime; the French parliament approved this change on its own. On 9 July, parliament members, having joined the cabinet in Vichy, voted 624 to 4 to scrap the 1875 constitution. The next day, parliament pushed the transfer of power a key step further, granting Pétain full emergency powers to formulate a new law of the land, by a vote of 569 to 80. This was no cabal; it was a transfer of power overwhelmingly approved by the current leadership. And it was less temporary than some deputies had hoped. As it turned out, parliament had voted itself out of existence for the war’s duration, and in the several months following those key votes of 9–10 July, Pétain consolidated executive, legislative, and judicial authority, laying the foundation for wartime authoritarianism.5

Yet Pétain never held executive power alone. Laval maintained his position as deputy premier until December 1940, when Pétain’s closest advisers convinced him to remove Laval from office. While Pétain sought to stabilize and renovate France, focusing on domestic reform, Laval ardently believed that Franco-German collaboration would establish the best position for France in a Nazi-dominated Europe. Men who were more sympathetic to Pétain’s vision for France succeeded Laval: Pierre-Etienne Flandin, from December 1940 to February 1941, followed by Admiral François Darlan until April 1942. By that time, the Germans were increasingly determined to extract additional resources from France—labor, raw materials, foodstuffs, and Jews. Dissatisfied by the level of cooperation they received from Darlan, the Germans forced Pétain to reinstall Laval in April 1942, revealing Pétain’s ultimate powerlessness.6

French authorities enjoyed relative latitude in cultural affairs during the Occupation only because the Germans very deliberately gave it to them. Hitler believed that cultural activities would offer the French people a useful distraction from the difficulties of everyday life and help placate urban populations. Similarly, Propaganda Minister Paul Joseph Goebbels believed it was in the German interest for the arts and cultural life to flourish, particularly in the French capital. The division responsible for censorship in Paris, the Propaganda-Abteilung, exempted the French from strict artistic censorship, allowing a wider range of expression than was permitted in the Reich. As a result, German officers enjoyed gallery exhibitions of “degenerate” art in Paris that would have been banned in Berlin.

This wartime approach to French cultural life reflected the Führer’s plans for the country within a New Europe dominated by the Thousand Year Reich. Hitler considered France a Rückendeckung, or “rear shield,” that would neutralize Germany’s western flank while he pursued his chief expansionist goal: Lebensraum (living space) for the German people in eastern Europe and Russia.7 Like other satellite countries, France would first and foremost support the German economy. It also would be a top vacation spot where troops and workers would rest their weary Aryan bones. With its exceptional artistic and cultural resources, France would provide tourist attractions, fashion, entertainment, and gastronomic delights.8

Soon after the armistice, on 23 June 1940, Hitler made his first and only trip to Paris. The German embassy, led by thirty-seven-year-old Otto Abetz, an ambitious young diplomat who lacked the official title of “ambassador” because of the military occupation, planned the itinerary. Abetz wanted to showcase for Hitler the splendors of Paris—its theaters, museums, historic buildings, and monuments. The Führer, who as an aspiring artist had twice failed to gain entrance to the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, fancied himself an art connoisseur and was grateful for the opportunity to visit the traditional artistic capital of Europe. His tour guides included architect Albert Speer, who offered commentary on French urbanism, and Arno Breker, the Reich’s official sculptor and a former denizen of the Montparn...