![]()

PART 1

An Organizational Analysis of Evaluation

![]()

1 Organizational Understandings

Rational, Learning, and Institutionalized Organization

In this chapter, I discuss evaluation from the perspective of organizational theory. There are three reasons for this.

First, a steadily greater proportion of the lives of modern individuals is structured by organizations. Our minds are becoming organizational. The mentality that dominates work organizations diffuse into society (Berger, Berger, and Kellner 1973), and to an increasing degree workplaces such as schools, hospitals, and universities are defining themselves as enterprises, and they must be managed as organizations.

Second, as organizations they take on the culture of evaluation. Organizations are themselves objects of evaluation, and therefore they seek to organize evaluation. They constitute the characteristic social arena in which the evaluations of our day take place. The organizational element in evaluation is in fact becoming more evident. Today, an evaluation should not only be used but be mainstreamed into an organization and lead to organizational learning. As a corollary, some of the most influential ideas in evaluation today are organizational ideas. When modern ideas about rationality and autonomy are executed in practice, this occurs most often in organizational form. Ideas about goals, plans, abstract rationality, management, bureaucracy, and organizational learning are important for understanding every modern organizational phenomenon. As we shall see in this chapter, elements of the modern organization are gaining ground through the history of evaluation. The attempts to bureaucratize evaluation are innumerable, and they constantly reappear in new forms. In this respect, we have never abandoned the idea of modern organization. Instead we cultivate the idea of organization in evaluation, too.

Third, organizational theory casts a fresh and renewing light on how evaluation actually works. Organizational theory, especially its recent elements, challenges fundamental understandings of what we mean by goals and objectives, evaluation criteria, and learning. Organization theory casts new light on how knowledge is used. If evaluation in contemporary society has become an institutionalized practice, organizational theory can help us understand why this occurs and with what consequences. Evaluation in organizations is our focus now (even if organizations are embedded in social-historical contexts). However, we will not unpack those parentheses until Chapter 3 onward.

“Organizationalization” of Evaluation

Some of the earliest contributions to evaluation viewed it as a technical-methodological tool, a form of assisted sense making, more reliable the more separated it was from human practice and ongoing human interaction (Schwandt 2002, 13). Even though some scholars continue to maintain this idea, several are increasingly aware that evaluation is strongly dependent on its social and organizational context. Context matters. There has been a movement from a naïve instrumental view of evaluation to a more sophisticated acknowledgment that both evaluation and its use are conditioned by organizational processes.

Management and organization have responded to this development. The ideal today is that evaluation must be integrated into all of the general processes in the organization: strategy, resource allocation, in-service training, and day-to-day management. Evaluation must be mainstreamed; this means “moving evaluation to the forefront of organizational thinking and behavior” (Sanders 2002, 2).

Many who work with evaluation think organizationally and sell organizational recipes for good and proper management. Evaluation embodies organizational thinking. Notice, for example, the difference between saying “Hi, my name is Lisa. I’m the evaluator” and the more contemporary approach: “Hi, I come from the quality department. I have management’s backing to come and facilitate a joint process about development of capacity for organizational learning.”

Several developmental features contribute to the fact that organizations now embrace evaluation. Early on, evaluators with participatory tendencies figured out that the organizational context of evaluation is of great importance. This led to an interest in organizational learning processes. In this way, the official side of management and organization also acquired an interest in evaluation. Evaluation must not be too haphazard; if it is simultaneously integrated into the organization’s general operations, perhaps it will succeed in channeling pressure for change so it is used constructively in the organization’s development.

That management and organization must begin to master evaluation is also connected to organizations themselves becoming evaluands. It is hardly coincidental that implementation research—the sister discipline of evaluation research, because it concerns itself with how policies are implemented in practice—has discovered that factors at the organizational level play their own role in the actual formation of public policies. Implementation of policy takes place in a complicated interorganizational context (Sabatier 1985; Winter 1994). Organizations add their own dynamics and motives to the implementation process. Fieldworkers employed in organizations experience constant pressure but also exercise their own judgment and thereby form the policy implemented in practice. If evaluators want to understand what results from public policy, they must look inside organizations.

Evaluations have broadened their perspective on the “content” of interventions directed toward clients and patients. The content cannot be separated from the organizational conditions under which it is provided. In a hospital, for example, an evaluation is carried out with the purpose of assessing not just how individual doctors do their job but whether the various specialists as a group have the capacity to provide coordinated, managed health care. We no longer evaluate teaching, but rather the learning environment. Organizational factors such as teamwork, cooperation, paper trails, organizational procedures, and management systems must be susceptible to evaluation, too. The more complex an evaluand, the more evident the need to study how its organization is managed.

This means organizations today must be aware that they are held accountable in evaluation terms. Control over organizations must therefore translate into control within organizations. The organization must adapt itself to evaluation. Therefore managers must also take responsibility for evaluation. A manager who wants to be taken seriously must master a vocabulary that includes terms such as quality, indicators, benchmarking, auditing, accreditation, and documentation. Management must be able to convert these terms into organizational practice. Managers must make their organizations evaluable and must organize their evaluations accordingly.

The ideal, therefore, is an “organizationalization” of evaluation. Evaluation becomes an important organizational function that cannot be left only to coincidence and to individuals.

As a corollary, we must also change our view of the evaluator. In much evaluation theory, this person is referred to as a fairly autonomous-thinking subject who has ideas and responsibilities in the same way as a natural person (even if the evaluator role is naturally a specific role). However, when evaluation is organizationalized, this idea of the evaluator dissolves, insofar as evaluation becomes an organizational functional entity. It is subsumed under the structures, values, and rules of the game. It is also institutionalized in the sense that, like other structurally defined organizational roles and functions, it can be exercised by interchangeable persons.

Modern sociologists have concerned themselves with what happens when such functions, formerly left to natural persons, become “organized.” Bauman (1989), for example, talks of the “adiaphorization” (exception from moral assessment) that characterizes modern organization. Herein lies a structuring of human relations on the basis of formal rules, procedures, and organizational principles, where following them is seen as a goal in itself, or in any case a necessity. In this connection, the organizationalization of evaluation can imply that moral considerations are made irrelevant to evaluation.

This is one of the far-reaching implications of the organizationalization of evaluation. In the following discussion, I delve more closely into three organizational theory models to trace some of the more specific possible effects of organizationalization of evaluation.

On Organizational Models

By an organizational model I refer to a particular way of thinking about organizations. Here, organizational models should not be confused with organizations or types of organization.

Models of organization incorporate both analytical, normative, and sociohistorical ideas. They are analytical, like other scientific models or abstractions; they simplify reality. Through simplification, they emphasize certain specific conceptual features that help us understand life in and around organizations. Without simplification, we would see only chaos.

Like other specifically modern types of knowledge, organizational thinking is born almost automatically reflexive, for it has evolved in close interaction with the practical “doing” and “living” of “organization” in society. Practical organizational problems encourage development of organizational models in order to come up with new ways of thinking that would help solve management problems. In turn, new ways of thinking are immediately marketed as new, better, and more-modern types of organization. Organizational and managerial models of good organizations have constantly imposed themselves on reality. Organizational models are theories of organization and theories in organization at the same time.

Organizational models both describe how organizations function and prescribe how they ought to function. In other words, organizational models are analytical and normative. We constantly behave in organizations with the expectation that what they do is fairly rational, even if our daily life experience tells us they are not.

This creates a dilemma as to how much complexity can be contained in the model. Every conceptual model must be fairly simple if it is to be heuristically useful. But without respect for complexity, descriptive models can be misleading. For example, formal models can ignore and suppress everything that informal organization does to make organizations function. Used prescriptively, simplistic models can have unpleasant and inappropriate consequences in complex reality.

On the other hand, this is exactly what organizations do. They seek to simplify reality so that it becomes manageable in some way according to particular values, norms, and procedures. Because values, norms, and the whole cultural fabric in society change over time, organizational models are sociohistorical symbols at the same time as they are analytical and normative ideas.

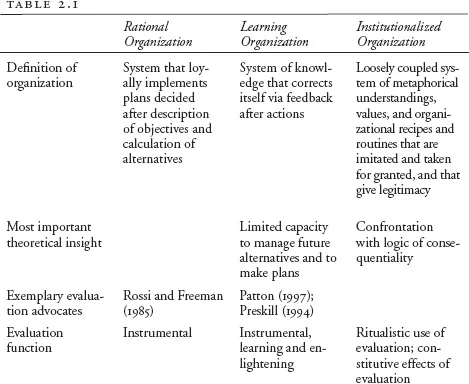

Here I describe three organizational perspectives, each of which operates with its own view of evaluation. In principle, one can analyze an organization with the help of a combination of several models, and perhaps in this way achieve a more complex understanding of the world than any single model would make possible. However, in this presentation I have chosen to treat each model separately. I present three models, which I call the “rational,” the “learning,” and the “institutionalized system” models. They are presented in a sequence of increasing complexity. This means I do not treat the three models equally. The more complex the model is, the later it is presented, and the more is written about it. (Only later may it turn out that the simple rationalistic and bureaucratic model of organization presented first also has a large imprint on today’s evaluation.)

In brief, the main features of the three organizational models and their view of evaluation appear in Table 2.1.

Rational Organization

No organizational model illustrates the social embodiment of the modern ideals of mastery of the world better than that of the rational organization. Rational organization aims toward maximum predictability. Once a set of objectives have been determined, the best possible arrangements are made to achieve predictable realization of these objectives.

The organizational characteristic that best expresses this approach is analyzed by Weber (1978) in his ideal-type definition of bureaucracy.

The proper way to do things is defined as a specific procedure. A procedure is a formalized way of ordering specific abstract components temporally (Berger, Berger, and Kellner 1973). The components are abstract in the sense that they can be treated in the same way by the procedure, regardless of their substantive content. Bureaucracy thus succeeds by means of organizing coordinating actions across distance, in time and space.

Documents and handbooks with scales, typologies, rules, and decrees lend assistance to rational organization. It will demand too much organizational attention if several cases are not handled in the same way. Conversely, the demand for mastery of the world leads precisely to abstract homogenization and standardization of the problems in this world, and the organizationally defined solutions to these problems, such that the world becomes manageable with the aid of organizational procedures.

As much as possible, management is carried out using written documents. This applies to both the procedure itself and the treatment of individual cases. Literacy is important for ensuring consistency and continuity over time and through space.

The procedure as form avoids, to the greatest possible extent, personal considerations, emotions, and histories, among employees and among those whom the organization encounters (for example, clients). Decisions are taken according to generalized rules. Optimally, technical and professional tools rather than human judgment are used. In other words, the client is viewed through the lens of a bureaucratic typology.

If one uses Schutz’s terminology (1973) regarding interpretations, organizational typologies are characterized by a low degree of “indexicality” in comparison to other typological systems. Indexicality refers to the specific meanings that can be connected to a typology when it is applied to a specific personal and contextual practice. Most organizational typologies are formulated in a jargon of management, finance, administration, or law.

Berger, Berger, and Kellner (1973) compare the mentality of bureaucracy with another large, typically modern form of mentality, the technocratic, which also includes manipulation with abstract components. The bureaucratic form of consciousness distinguishes itself, however, in that the technocratic form must give more consideration to substantive properties of the tasks it is dealing with. Construction of a bridge, for example, requires attention to the physical properties of the materials as well as the load capacity of the bridge. Bureaucracy is much less constrained by limits of the physical world; instead, it creates its own kind of world. The objects dealt with are defined in abstract terms on the basis of bureaucracy’s own classification systems. Indexicality is low.

In the world of bureaucracy, special value is connected to the procedure itself. If a technocrat, for example, wants to produce a passport document, it does not matter how it is produced, only that it looks genuine. For a bureaucrat, though, how the passport is produced is critical (Berger, Berger, and Kellner 1973).

To ensure maximal predictability, the organization’s total work tasks are divided so that the organizational structure reflects the classification of tasks. In this way, each task obtains a corresponding specialized competence to carry out precisely this task. The competencies are divided in the organizational structure, corresponding to the task division. This means that planning of tasks and implementation of tasks are separated. In any individual place in the modern organizational structure, there are skills and competencies to execute only a single specialized task, and there is often no total overview of the entire organization’s mode of functioning (Berger 1964). Only in one central place in the organization is it assumed that this overview exists. The remainder of the organization is reduced to being an instrument for this central, rational brain.

This process—making the organization into an instrument—naturally entails a degree of value ambiguity. The tool can evolve into a social form in itself that becomes its own purpose. As described here, the modern bureaucratic organization embodies what Weber called formal rationality, which is expressed in a procedure that gives the impression of calculability, predictability, and efficiency (Ritzer 1996, 138). Formal rationality is thus abstract rationality. It appears separated from substantive values and instead relates itself to “universally applied rules, laws, and regulations” (1996, 136). In rational organization, there is always a risk that the organization as instrument and its legitimate procedures become a social form maintained for its own sake, independent of other substantive values.

Evaluation in the Rational Organization

When rational organization pursues the greatest possible predictability in operations, there are great advantages of operating entirely without evaluation. In a pure, classic modern organization, it is appropriate to operate with plans, not with evaluation. But if evaluation is to function within the frameworks of rational organization, the latter ensure incorporation of the former into predictable procedures.

Evaluation must be planned to the greatest possible degree, and be in accordance with the organization’s objectives. A rational organization cannot risk being evaluated on the basis of unpredictable criteria. For evaluation to be used as rationally and predictably as possible, several strict demands are made on the evaluation process. The evaluation criteria must be set up in advance and in strict accordance with the approved organizational objectives. The evaluation process should follow a predefined rational plan and not be open to surprises and c...