![]()

One

Beyond Appropriation

Reclaiming the Revolutionary Amichai

Authentic art of the past that for the time being must remain veiled is not thereby sentenced. Great works wait.

—Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory1

I. Useful Poet

In the fall of 1999, when the seriousness of Yehuda Amichai’s final illness was already public knowledge, and the Israeli media was filled with tributes by critics, fellow writers, and politicians, it was the outpouring of love from common readers that Amichai found truly overwhelming. “It’s amazing,” he told me in the hoarse whisper that had replaced his steady voice, “real love.2 And the poems are useful to them.” “The main thing is to be useful [ha-ikar li-hyot shimushi],” Amichai would often say, in his inimitable mixture of irony and consent, invoking perhaps the socialist mindset of an earlier time, when being useful to one’s community was considered the highest virtue. Providing useful poetry was indeed something he was always proud of, especially when it was ordinary human beings, not the mechanisms of state or institutional religion, that would find some practical application for his words. And it didn’t matter if the context of use was sublime or ridiculous: from wedding vows and eulogies to lawsuits and hair salon ads.

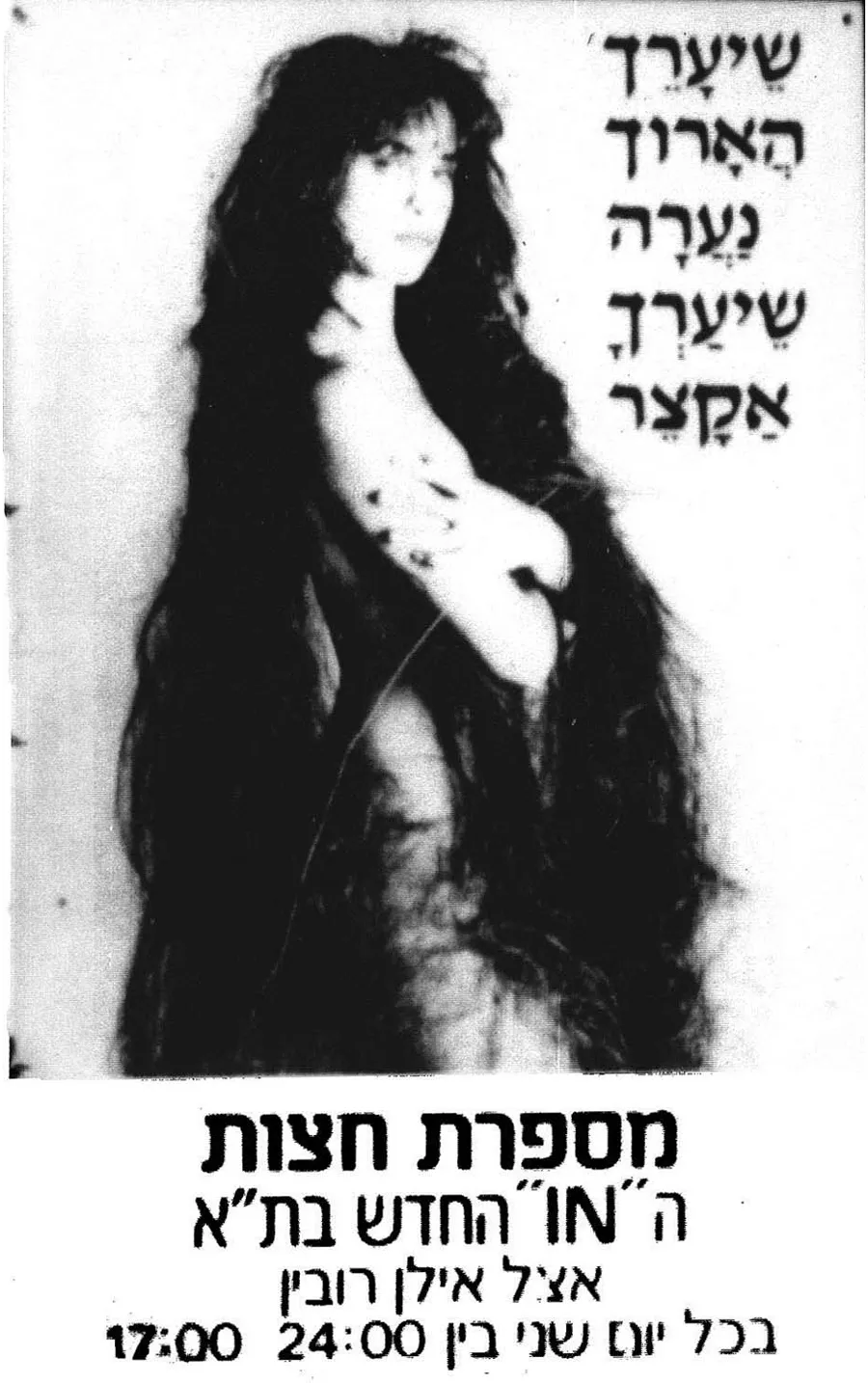

The advertising poster on page 26 illustrates quite vividly the absorption of Yehuda Amichai’s poetry into the fabric of the quotidian, a fabric that in Israeli culture still includes poetry.3 The refrain of Amichai’s beloved early poem “Balada al ha-se'ar ha-arokh ve-ha-se'ar hakatzer” (“A Ballad on the Long Hair and the Short Hair”) starts with the lines: “His hair was shaved off when he got to the base, / Her hair remained long and without a response.”4 By the end of the poem, the lovers—separated by an antiheroic, alienating modern army rather than a tragic Shakespearean family feud—can no longer hear one another, and the third line leading into the refrain and rhyming with it, is broken in two: “‘ma at omeret?’ / ‘ma ata omer?’” (“What are you [fem.] saying?” / “What are you [masc.] saying?”).

The fragmentation of the dialogue in the poem’s refrain (dialogue and refrain being the very features that the ballad genre marks as most salient) thematizes the ultimate impossibility of communication between the young lovers once the man is drafted into military service: “se'arekh ha-arokh, na'ara. / se'arkha ha-katzer” (“Your long hair, girl / Your [masc.] short hair”).5 The hair salon ad puns on this refrain, neutralizing in its commercial appropriation the poem’s mournful protest against the emasculation brought about by conscription, as well as the military crew-cut’s allusion to the Samson story that carries this meaning. The ad replaces this nuanced symbolism and intertextuality with the literal promise of a fashionable and fetching co-ed salon cut. It supplants the dialogue between the lovers with the hairstylist’s offer to shorten (le-katzer) both men’s and women’s hair: “Your long hair, girl / Your [masc.] hair I will cut short” (se'arkha akatzer). In modern colloquial Hebrew pronunciation, which assimilates most ha sounds to an a, the ad’s pun produces a virtual homophone between the poetic form of the definite adjective “the short” (ha-katzer) and the hairdresser’s promise “I will cut [it] short” (akatzer). When I showed Amichai my photograph of the poster and asked him if he didn’t mind having his poem mangled like that, he answered, smiling: “On the contrary [le-hefekh]! I love to be used, to be exploited.” And so he was. But not always as he would have liked.

Figure 1. Storefront Poster: Your Long / Hair / Girl / Your [masc.] Hair / I Will Cut Short / Midnight Hair Salon (Arlozorov Street, Tel Aviv).

Amichai’s poetic system differentiates throughout between two forms of exploitation that his work treats as profoundly distinct: on the one hand, those largely spontaneous, populist processes that have resulted in the incorporation and assimilation of his poetry into the fabric of everyday life, processes his work thrives on, indeed explicitly asks for; and on the other, the hegemonic mechanisms of cultural appropriation, leading to an official reception that constructs him as a national poet and politically neutralizes his sustained critique of institutional nationalism, state bureaucracy, and clericalism. Though I do not necessarily share the rather idealistic view that the two mechanisms can so clearly be distinguished, it is important to me to suggest the ways in which this distinction is crucial to Amichai’s poetic ethics. In the process, I will also argue that no matter how powerful the mechanisms of appropriation become, the poetry—in its absorption into the practice of quotidian existence—continues to have a radical and radicalizing effect.

Liron Bardugo has suggested, in a perceptive article, that within all strata of Israeli culture “Yehuda Amichai is quoted almost inadvertently, as part of the sounds of everyday life and the noises of the street,”6 and this despite what he describes as Amichai’s rejection of a poetics of nationalism and collectivity. Becoming an inadvertent quotation is indeed the ultimate fulfillment for the verbal artist who places a high value on the complete integration of poetry into the lives of ordinary people.7

One of Amichai’s most famous early poems, “Lo ka-brosh” (“Not Like a Cypress”),8 rejects traditional elitist conceptions of the poet as lone giant or unique genius and offers a series of alternative populist and utilitarian models for the poet’s social and cultural usefulness. In negating the tall, visually salient cypress and its towering human stand-in, King Saul, as models for the poet and offering instead, for example, the image of small and dispersed raindrops that are absorbed “by many mouths,” Amichai opts for inconspicuous usefulness over a socially useless prominence (the cypress produces no edible fruit). Indeed, this poem rejects the notion that the poet is entitled to any privileged elite position or granted any aesthetic chosenness that would free him or her from the need to be of use to their society.9

Less than a year before Amichai’s death, it was the novelist David Grossman who articulated with the most poignant simplicity the source of Amichai’s great popularity with the common reader over a period that spanned close to half a century. In an interview in Ha'aretz, Grossman talks about Yehuda Amichai’s poetry as a constant companion:

This poetry, in its great intimacy, provides us with first names with which to address life situations where, having run out of words, we’d normally be whittled down to clichés [mitradedim li-klisha'ot]. Along comes an Amichai line and gives us words [ve-notenet lanu milim]. . . . Because he reaches all the way inside the everyday, you suddenly feel that each moment, even the most banal, is shot through with light. . . . [Amichai’s] words have become part of my interior monologue, and not mine alone.10

Grossman adds, “He has accompanied me both as a teenager and during army service—in my loves, in courting girls, as well as in my daily family life.” This ordinary description masks in fact an allusion to an important metapoetic line from an Amichai poem (“Summer Rest and Words”), milim melavot et chayay (“Words accompany my life”), which describes the integration of intertextuality into daily experience.11 And when Grossman says that thanks to Amichai’s words, even the most banal moments become—literally and figuratively—shot through with light, he’s again invoking a foundational Amichai image: the ordinary beloved woman as the embodiment of—and substitute for!—divine glory, as she is “standing by the wide-open fridge door, revealed / from head to toe in a light from another world.”12 Grossman’s allusively charged yet misleadingly simple diction may be the ultimate homage to the increasingly Amichaiesque poetics of usefulness and accessibility that Grossman himself has been pursuing in the years after publishing his novel, See Under: Love.

II. The Politics of Verbal Art

In the next chapter I will explore what goes into making Amichai a usable, or simply useful, poet. Here, however, I would like to focus on the other half of the equation: his poetry’s systematic co-optation and appropriation by hegemonic discourses of state and institutional religion. Amichai’s poetry, despite its oppositional stance, has been thoroughly appropriated in two systematic ways, each corresponding to a different geographic center of readership: for nationalist official ceremonies and commemorative functions by various Israeli state-apparatuses (e.g., the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Defense); and for religious ritual by the organized Jewish American community, as part of its investment in Yiddishkayt-lite.13 Both types of appropriation require, as I argue in section III below, that central aspects of Amichai’s poetry be rendered invisible. In both cases, Amichai’s sardonic deflations and critique of these very ceremonies and institutions must be ignored in order for his appropriations as National Poet or Religious-Bard-for-Secular-Jews to be as thoroughly successful as they have been.14 This is, ultimately, the most cynical distortion of Amichai’s egalitarian ideal of the useful poet.

What I find most disturbing is that generations of progressive young Israeli readers have been turned off from Amichai’s poetry because they came to identify it with its various official commemorative and ritualistic reifications—to all of which they were exposed from their earliest school years. What I wish to do, then, is peel away a few of the many layers of interpellation in order to make Amichai freshly readable again. I am motivated, above all, by my passion for his poetry and the sense that its prominence has, paradoxically, rendered it illegible. In reclaiming Amichai for a new/old reading and by reconstructing some of the shock value it had when he first appeared on the scene, I do not delude myself that any of his systemic co-optations can be fully undone or, for that matter, that my proposed rereadings are not in themselves expressions of my own political, aesthetic, and even academic-institutional situatedness. But I do hope, in laying bare my own positionality, to avoid some of the mystification that characterizes Amichai’s ideologically driven appropriation by the “establishment.”15

That Amichai was not always received in Israel as the National Poet of Celebratory Statism is brought vividly home by a fascinating recent piece of archival detective work. Rafi Man, as part of his doctoral research, uncovered the minutes of two powwows held at David Ben-Gurion’s office in March 1961.16 Among those present were the young kibbutzniks Amos Oz, who would become one of the major novelists of the Statehood Generation, and Muki Tzur, who would later emerge as a central historian of the Zionist labor movement. During one of these meetings, while the participants complain to their political father-figure about “the nihilism” and “loss of values” (ovdan arakhim) typical of the Hebrew literature of their time, Amnon Barzel, then the youth coordinator of the centrist-labor kibbutz movement (Ichud), brings up the poetry of Yehuda Amichai and adds: “He is an excellent poet but extremely dangerous [mesukan ad me'od].”17 He then offers to send Ben-Gurion a copy of Amichai’s book. I propose that we take seriously the fact that in March 1961 these young intellectuals, seeking access to the seat...