![]()

PART ONE

Rationality and Decision-making

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Rationality, Social Preferences, and Strategic Decision-making from a Behavioral Economics Perspective

SIMON GÄCHTER

Introduction

The central assumption of the rational choice approach is that decision-makers have logically consistent goals (whatever they are), and, given these goals, choose the best available option. This model, in particular its extension to interactive decision-making (game theory), has had a tremendous impact in the social sciences, in particular economics, and has allowed for great theoretical progress in the latter. For instance, the model and its formalization have led to important insights into the functioning of economic systems (see Mas-Colell, Whinston, and Green [1995] for a leading textbook account). They have also shed new light on numerous nonmarket processes, such as crime, addiction, family behavior, political decision-making, and organizational behavior (Coleman 1990; Becker 1993; Hechter and Kanazawa 1997; Gintis, Bowles, Boyd, and Fehr 2005). Rational choice theory in the form of game theory is now the core theoretical tool of economics. It is therefore certainly justified to speak of the rational choice model as a “success story.”

Rational choice models often assume that agents are “unboundedly rational” and always know what is best for them. This assumption has long found many critics (Simon 1982). A further assumption that is not part of the canonical rational choice model but is frequently invoked in applications is that agents are primarily self-regarding. This assumption has been challenged in particular in the last decade through the accumulation of empirical, in particular experimental, evidence that has shown substantial and robust deviations from what selfishness predicts.

In the past the discussions about the fruitfulness of the rational choice approach were based largely on philosophical convictions and less on facts. In this chapter I will argue on the basis of insights from behavioral economics that the usefulness of the rational choice approach is also an empirical question and not just a philosophical one. My approach is related to that of Hechter and Kanazawa (1997), who argue for the fruitfulness of rational choice explanations by discussing its empirical successes across a large variety of interesting sociological domains. My arguments are based on data from many laboratory experiments which all share the feature that the theoretical predictions are derived from rational choice models (typically game-theoretic models) and that decisions in the experiments have financial consequences for the participants, which give them an incentive to take decisions seriously. Specifically, I will use experimental results to argue that one can acknowledge that humans are boundedly rational and nevertheless appreciate the predictions made by rational choice models that at times rest on unrealistically strong assumptions. Moreover, I argue that a rational choice approach does not imply assuming that everyone is selfish.

I start by giving a short characterization of the canonical rational choice model, including the selfishness assumption. With the help of one famous research program on the functioning of experimental markets I will illustrate one main point that will recur several times. I argue that one can fruitfully use rational choice theory to predict social outcomes even if the assumptions entering the model are empirically invalid. I will first discuss the success and limits of the rational choice approach. Then, I focus attention on the empirical investigation of the selfishness assumption. I will present evidence from several economic experiments that have been used as tools to uncover the structure of people’s “social preferences.” Numerous experiments have shown that the selfishness assumption is invalid as a description of typical behavior, although in all experiments we do find selfish people. The results on social preferences raise the challenge of how to model them, and I will sketch some attempts.

Rational Choice and Homo Economicus

THE RATIONAL CHOICE MODEL

My main goal here is to set the stage for the subsequent analysis. For fuller accounts of various aspects and criticisms of the rational choice approach I refer to Coleman (1990); Hedström (2005); Elster (2007); Lindenberg (2008); and Gintis (2009).

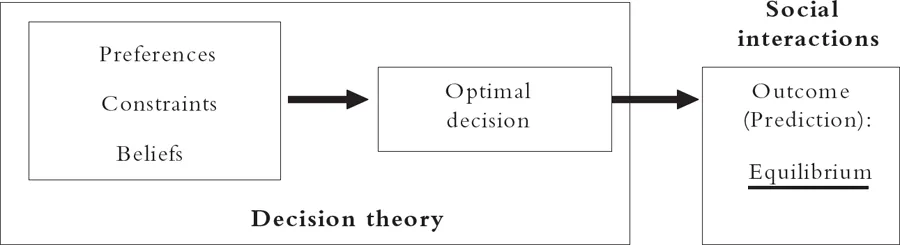

The rational choice model aims to explain the decisions of individuals and the individual and, in particular, the social consequences of those decisions. Figure 1.1 illustrates the core elements of the rational choice model. It is useful to distinguish two conceptual buildings blocks: decision theory and equilibrium theory. Decision theory describes how decision-makers should make decisions (normative approach), or actually do make decisions (positive approach). In case individuals interact, a so-called solution concept describes the predicted social outcome. The usual assumption is that the resulting outcome will be an equilibrium.

Decision theory typically makes a conceptual distinction among preferences, beliefs, and constraints. Preferences describe how individuals rank the available alternatives according to their subjective tastes. Beliefs are the second conceptual building block behind the rational choice model. For instance, in which stocks you invest will probably depend on your expectations about the future earnings potential of that stock. However, choice depends not only on one’s subjective taste and beliefs but also on constraints. Constraints are the set of alternatives that are available to an individual. For instance, you might prefer a Ferrari to a Ford, but your available income might constrain you from buying a Ferrari. After specifying preferences, beliefs, and constraints, the analysis proceeds by assuming that individuals choose a feasible option that best satisfies the individual’s preferences (“the utility-maximizing choice”).

FIGURE 1.1. The rational choice framework.

The rationality assumption enters the picture on the conditions that are placed on preferences. The typical rationality assumptions are that (i) preferences are complete, which means an individual can compare all relevant alternatives and rank them, (ii) preferences are transitive—that is, if an individual prefers alternative A over B, and B over C, then that individual should also prefer A over C, and (iii) preferences are independent of irrelevant alternatives—that is to say, the relative attractiveness of two options does not depend on other options available to the decision-maker. This rationality assumption ensures that preferences are noncyclical and therefore contain a “best element,” which will be chosen if available. Notice that the rationality assumption is nothing more than a consistency requirement and is completely mute on the content of preferences. This has not gone without criticism. For instance, Amartya Sen, in an influential article, has mocked this conception of economic man as being a “rational fool” (Sen 1977).

Rational choice theory becomes a theory of social interactions if the individual decision-makers interact with each other. The social sciences are typically interested in the social outcomes of the interaction of individuals. One particularly important approach, especially in economics, is to analyze social outcomes from an equilibrium perspective. An equilibrium is a situation in which, given the decisions of all other decision-makers, no agent has an incentive to change behavior. If there is still an incentive to change behavior for at least one decision-maker, then the resulting outcome of the social interaction cannot be an equilibrium.

Two important classes of social interaction are markets and (small) group interactions. In markets decision-makers face prices and have to decide how much they want to produce or buy at given prices and income. In the prototypical case a single individual cannot affect prices and thus takes them as given. An equilibrium is a situation in which at given prices agents want to change neither their production plans nor their demands (for a comprehensive textbook account, see Mas-Colell et al. 1995). In strategic situations an equilibrium is reached if, given the strategic behavior of other players, no one wants to change strategy. Thus, in many social science applications the analysis does not stop after looking at individual decisions but proceeds to predicting social consequences under the assumption that the resulting outcome will be an equilibrium. Of course, it is an empirical question whether the equilibrium prediction (which is derived for specific assumptions about people’s preferences) is consistent with the data.

THE SELFISHNESS ASSUMPTION

The rational choice approach is a flexible framework that can account for any preferences as long as they obey the consistency axioms. This flexibility is also a weakness, because if almost any preferences are permissible almost anything and therefore nothing can be explained. For that reason economists very often made additional preference assumptions to give the rational choice analysis more structure or assume that people have the same preferences (see, for example, the influential discussion by Stigler and Becker 1977). The most common and long-standing assumption is that decision-makers are self-regarding. Self-regarding agents will take the welfare of others into account only for instrumental reasons to increase their own well-being.

In essence there are two justifications for the selfishness assumption. A first justification is tractability in modeling, as selfishness can simplify the analysis considerably. The selfishness assumption often allows for exact predictions, which can be confronted with appropriate data that might refute the selfishness assumption. Moreover, it is often of independent interest to understand what would happen if everyone were selfish. Understanding the consequences of selfishness serves therefore as an important benchmark for understanding nonselfish behavior.

I have already alluded to a second justification of the selfishness assumption, that assuming nonselfish preferences, although logically possible, is tantamount to opening “Pandora’s Box”—which in this case means that any bizarre behavior can be rationalized. This argument has considerable merit in the absence of empirical means to assess the structure of people’s social preferences. Yet, as I will demonstrate below, the development of experimental tools allows us to observe people’s social preferences under controlled conditions. Behavioral scientists have lately even added neuroscientific tools to understand the neural mechanisms behind people’s social preferences (Fehr 2009b).

FIVE METHODOLOGICAL REMARKS ON THE RATIONAL CHOICE MODEL

I conclude this discussion with five methodological remarks and refer the interested reader to Gintis (2009) for a more in-depth discussion of the issues raised here. The first remark concerns the selfishness assumption, to which we will return in more detail below. Nothing in the rational choice framework dictates that preferences have to be self-regarding; the only necessary assumption is that preferences obey some consistency axiom such that optimal choices are logically possible. Thus, a rational decision-maker can have other-regarding preferences and still obey all the rationality axioms. As we will show below, there is substantial experimental evidence for both that many people are not purely self-regarding and that other-regarding preferences often do obey consistency axioms (at least in simple situations). We will also show evidence that behavioral patterns in experiments in which social preferences are important are consistent with predictions derived from rational choice models.

Second, one may criticize the rational choice approach as being unrealistic in the sense that human decision-makers do not reason and behave like those portrayed in the theory. This argument has a lot going for it, as has been pointed out emphatically from different angles by Simon (1982); Gigerenzer and Selten (2001); or Loewenstein (2007).

The limits of the rational choice approach can be discussed with the help of Figure 1.1. Psychologists and other behavioral scientists have long argued that people are faulty statisticians, as they often do not update information rationally and therefore hold nonrational beliefs, they overweigh small probabilities and underweigh large probabilities, and they fall prey to various framing effects (see, for example, Kahneman and Tversky 2000; Lindenberg 2008). Furthermore, people are often swayed by their emotions and evaluate options differently depending on whether they are in a “hot” or a “cold” state (see, for example, Vohs, Baumeister, and Loewenstein 2007). People make mistakes in predicting their future utility (for example, Loewenstein, O’Donoghue, and Rabin 2003) and are often too impatient and show weaknesses of will (Loewenstein, Read, and Baumeister 2003).

These are all important findings. They have been possible because exact model predictions as derived from formalized rational choice theories were confronted with appropriate data. These findings have stimulated extensive research in all social sciences. In economics they have helped to pave the way for “behavioral economics,” which is the integration of psychological and sociological insights into economics. Behavioral economics is now branching out into the various subdisciplines of economics and transforming them by integrating psychological and sociological insights into rational choice frameworks (see Camerer, Loewenstein, and Rabin 2004; Diamond and Vartiainen 2007). This development would not have been possible without the rational choice approach, which helps pinpoint the problems in standard theory.

Yet, as I will demonstrate by way of an example below, a rational choice analysis often makes surprisingly accurate predictions despite considerable violations of some assumptions that underlie the theory. This point has already been made by Becker (1962). Such a viewpoint does not necessarily imply discarding the importance of the empirical findings mentioned above, or a methodology that cares only for prediction accuracy and not so much for the empirical validity of the underlying assumptions. Quite the contrary, I will discuss evidence that points to the violation of the selfishness assumption as being a cause of a failure of prediction accuracy in several games of interest to social scientists. It is an empirical question how sensitive theoretical predictions are to particular violations of underlying assumptions. The rational choice approach provides theoretical rigor in uncovering which violations matter for prediction accuracy and which not. Moreover, very often we are interested in the comparative statics prediction of a model and, as we will see throughout this chapter, these predictions are often empirically validated.

Third, and somehow relatedly, equilibrium theory does not explain how a particular equilibrium is act...