![]()

1 PRELUDE

The chief concern of this book is the relationship between globalization and security or insecurity. There are two central questions: How are they connected? And what are the implications for world order?

I want to map the debates among policymakers and scholars on these issues and develop a single concept called hyperconflict. It does not cut against the findings of empirical studies, which painstakingly show that in recent decades, the frequency of armed conflict has decreased or, some say, remained level. Instead, my core argument is that a novel pattern is forming. Insecurity is being globalized in an emergent configuration of hyperconflict, a galaxy of conflicts in historical motion. In other words, globalization is propelling a unique confluence of forces that portends hyperconflict. There is a reorganization of political violence, pervasive uncertainty marked by a rising climate of fear, changing structures of armed and other forms of conflict that are not necessarily in the hands of governments or their agents, and growing instability at the world level. The objective in this work is to show concretely how and why this is occurring, and what it means for future world order.

DEBATES AND VISIONS OF WAR AND PEACE

In the contemporary phase of globalization, the period from the 1970s, transnational processes rapidly slice across national territory and are also implanted inside this space. States seek to benefit from them as well as protect their citizens from threats such as global crime and pandemics brought by these transformations. The quandary is that while globalization erodes the principle of territoriality, the imperative of national security affirms the salience of homeland jurisdiction. These forces pull in opposite directions, altering the balance between security and insecurity. In this uneasy correlation of the old and the new, the national and the global blend, though not seamlessly.

In coming to grips with this shift, an oft-stated view is that globalizing processes are prone to peace because the expansion of commerce favors cooperation. It is also said that the spread of democracy fosters peace. Added to this, technological advances, particularly in communications and transportation, increase awareness and can be a spur to building commonality around the world.

Yet many of the same global structures that convey knowledge and other commodities may heighten insecurity and conflict. The Internet, the ease of travel, and financial networks enable the contagion of violence, as with crossborder criminal and terrorist organizations. Modifying the scale of action and the scope of cooperation or conflict, globalization empowers certain political actors, such as transnational advocacy networks and local civil society groups. It also reduces regulatory barriers and lowers the cost of transactions—for example, for flows of weapons and certain types of attacks. With contemporary globalization, the cost advantage now works in favor of nonstate actors. They can convert devastating strikes, such as the ones on September 11, 2001, at a price estimated at $250,000, into a multibillion dollar toll for damage and redress (Robb 2007, 31). According to Joseph Stiglitz and Linda Bilmes’s calculations (2008), the overall cost of the follow-up to 9/11, the Iraq conflict, is even higher: three trillion dollars or more.

Lurking behind these factors are the deep drivers of security and insecurity, detailed in the ensuing pages. One is intensified competition that agglomerates markets. Another thrust is the amassing of power, the lead actor being the U.S. state. It, in turn, selectively induces and seeks to manage a diffusion of power that extends beyond state power. But how can the analyst bridge these geoeconomic and geopolitical realms?

To grapple with these big issues, one can trudge back over two hundred years to Immanuel Kant’s philosophical writings about the quest for eternal peace. Putting forward seminal ideas about the connections between war and peace, he, like all great theorists, transcended his time and inspired thinkers to the present day. Critically, Kant’s Perpetual Peace ([1795] 1948) offered a vision of a federation of republican states that would stave off new wars. To ensure security among themselves, states would give up lawless freedom and would agree to an expanding union based on cosmopolitan norms and world law. Renouncing a utopian perspective, Kant called for balancing morality and interests, subject to various approximations, an aspiration that was to be gradually realized by a universal order.

Striving for perpetual peace is a matter pursued by other authors mindful of the historical links between order and war. Whereas a Kantian position stresses the normative foundations of action, Marxist dialectics identify material power as the ground for protracted conflict. Both Kant and Marx knew that struggles between self-interested groups are the stuff of history—in the Marxist schema, entailing class war and ultimately the atrophy of the state. The one more ideational than the other, these sage observers were cosmopolitans who sought the means to curb the bitter antagonisms that afflict society and are used to sanctify war. These renowned thinkers understood the perils of outbreaks of war as a way to build lasting peace, later enshrined in slogans such as “the war to end all wars.”

Inspired by the economic historian Charles Beard, the idea “perpetual war for perpetual peace” depicted the foreign policies of the United States in the run-up to World War II. Beard (1946, 1948) reproached Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Truman for steadily preparing for war while proclaiming Washington’s peaceful intentions. So, too, George Orwell’s antiutopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four ([1949] 1950) showed how a new world order could be organized along the lines of perpetual war, represented satirically in his narrative as a quest by free peoples for perpetual peace. The notion of peace through war is thus similarly treated by Beard and Orwell: for Beard, in the sense of the “right” to conduct military operations against any power that threatens peace; and for Orwell, as an internal affair in which the state stirs up fear and uses foreign policy as a device to control its own citizens.

Fictionalizing a situation in which three major powers are constantly at war with one another, Orwell’s story makes the point that “[t]he war … if we judge it by the standards of previous wars, is merely an imposture…. But though it is unreal it is not meaningless. . . . The very word ‘war’ … has become misleading. It would probably be accurate to say that by becoming continuous war has ceased to exist” (Orwell [1949] 1950, 204–5). In Nineteen Eighty-Four, the foremost powers do not fight one another; they live in perpetual peace; and this permanent peace is no different from permanent war. “[T]he object of the war is not to make or prevent conquests of territory, but to keep the structure of society intact” (204–5). Orwell’s sinister scenario may be regarded as commentary on the historiography of his own day and more generally as a resemblance to, or an embodiment of, the meaning that Beard had conveyed.

The insight that war-makers offer urgent reasons to wage war in order to secure peace is investigated in empirical research by other revisionist historians (Barnes 1953; Divine 2000) and by various social critics. When in the throes of war, President Richard Nixon sought to convince the public that the U.S. military was extending the battlefield and bombing Cambodia so as to bring peace to Vietnam, Seymour Melman (1970, 1971, [1974] 1985), among others, showed who benefited from the war economy in the late twentieth century. A professor of industrial engineering, Melman provided meticulous empirical accounts of technological advances in the industrialization of warfare and the special interests that it serves. In this tradition, and post–9/11, dissident writers such as Gore Vidal (2002) popularized the epigram of perpetual peace through perpetual war. It may be applied to President George W. Bush’s preparations for war in Iraq. In his 2002 State of the Union address, he pledged the largest hike in defense spending in twenty years and justified it on the ground that North Korea, Iran, and Iraq “constitute an axis of evil, arming to threaten the peace of the world” and that “the price of freedom and security … is never too high” (as quoted in Daniel 2006, 13; emphasis added).

Going further, the models of perpetual peace and of war for peace may be joined by a third image: perpetual peace by enduring competition. The first two are skeletal, and the third alternative adds flesh to precursor frames. It posits that the compression of time and space marking contemporary globalization brings capitalists into more direct competition with other capitalists. These head-on encounters may be deemed hypercompetition, a form of restructuring elaborated by Richard D’Aveni (1994), a professor of strategic management and a fellow of the World Economic Forum (WEF).1 He documents the practices of “aggressive market disruption” and “smart bombing” to beat competitors, “counter-revolutionary strategies to buy time,” and maneuvers for “building corporate spheres of influence.”

The language of hypercompetition likens this combativeness to war. For example, at an AT&T plant in Denver, a poster over Northern Telecom CEO Paul Stern’s photo broadcasts the statement, “Declare business war. This is the enemy” (D’Aveni 1994, 213, 319; emphasis in original). Researchers in strategic management (M. Porter 1990; D’Aveni 1995) interviewed many CEOs who use such war metaphors and adopt slogans like Honda’s: “Annihilate, crush, and destroy Yamaha!” (D’Aveni 1994, 376). In this lexicon, strategies for escalation and conquest are expressed in increasingly aggressive terms.

Notwithstanding efforts to negotiate international competition agreements (chapters 4 and 6), the manner of combative maneuvering to increase market access takes on aspects of a Hobbesian “warre of all against all” on the terrain of global capitalism, with a shift in some of its bedrock. And as Michel Foucault (2003, 92–93) pointed out, Thomas Hobbes’s primal state of war is not a conflagration involving actual weapons and bloodshed but a theater of presentations and representations: in Hobbes’s words, “Warre consisteth not in Battel onely, or in the act of fighting; but in a tract of time, wherein the Will to contend by Battel is sufficiently known” (as quoted in Foucault 2003, 92–93).2 When security is lacking, a “tract of time” marks the state of the field of contestation.

In our age, this field is a hypercompetitive landscape. The terrain is situated in a business environment that prizes efficiency and finds novel ways to cut costs. Speeded by new technologies, the rise of transnational capital and increasing labor mobility have had a profound impact. Yet hypercompetition is more than an acceleration of the earlier practices of capitalism. Whereas John Rockefeller and Henry Ford had sought to secure the stability of markets and their own firms, now the emphasis is on destabilizing the business environment and creating risks. Chief executives even want to knock their own organizations off balance (Sennett 2006, 41). These corporate officers are not merely competing in a benevolent manner, as imagined by conventional economists, but are carrying out a belligerent hypercompetition.

Meanwhile, national production systems are being supplanted by globalized firms that disperse activities around the world. France, for example, has long known hypermarchés (hypermarkets) at home. Firms based there, like Carrefour, the world’s second-largest retailer, have planned a pugnacious strategy for expansion in certain overseas markets. In the words of its chief executive, “we can attack 2006 much better armed” (as quoted in Jones and Rigby 2006). Key to this agenda is transnational finance—including approximately $2 trillion per day in currency exchange—which moves rapidly across borders. Some of it locates offshore so as to avoid regulatory authority.

The growth of the Asian economies has fueled this spike in global competition. The tailwinds of rising competition from Asia brought major benefits to some sectors in the United States: an enormous volume of investments, brisk growth in overall demand for commodities, and the purchase of large dollar reserves (usually deemed an advantage though sometimes seen as a drawback). But competition over energy supply, trade, and currency-rate imbalances pose political as well as economic risks. This competition involves the explosion of highly leveraged financial instruments (unregulated hedge funds, including the use of derivatives by speculators) and the conditions for volatility of the dollar, especially as global interest rates equalize.

Intensifying competition is of course historically rooted. It became accentuated in the twentieth century with the combination of a decline in the U.S. real economy (the production of goods and services) and the ascendance of financial instruments (Arrighi 2005; Patomäki 2007). Beginning in the 1970s, there were basic shifts, notably the fall of national Keynesianism, the demise of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, the rise of neoliberalism (a set of ideas and a policy framework for accelerating global market integration), the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the transition to a post–Cold War order.

In this restructuring, competition is not necessarily the same as conflict. Yet competition, in Adam Smith’s sense of the term, involves conflicting self-interests. Or in Max Weber’s usage, competition is a form of “peaceful conflict … in so far as it [the latter] consists in a formally peaceful attempt to attain control over opportunities and advantages which are also desired by others” (Weber [1947] 1969, 132–33). And competition can mean conflict under given conditions: sometimes from the unfinished business of the Cold War, initially in countries like Afghanistan and Angola but increasingly linked to the unevenness of globalization.

Hypercompetition is heavily but not totally American in several of its facets: the long reach of U.S. markets, the organizational technologies that originated or were adapted in the United States, U.S. predominance in spending for research and development (R&D), Anglo-American neoliberal ideas about the ordering of economy and society, the U.S. lead in information systems (as in American-fashioned software and computer operations), the spread of the American variant of the English language, and the United States’ continuous capacity for cultural innovation or, one might say, the wherewithal for renewal.

These assets are associated with what Joseph Nye calls “soft power”—the means to get others to do what you want (Nye 1990). Whereas Nye posits that Washington is “bound to lead,” Samuel Huntington holds that the United States is a “lonely superpower” in a transitional system in which it will become a more “ordinary” major power (Huntington 1999). Huntington is right to jettison the language in vogue during the Cold War, when “superpower” described the position of the United States and the Soviet Union relative to the standing of other countries, and to call for new analytical categories appropriate to a dynamic shift in world order.

After 1989, the United States is extraordinary in its unparalleled military capacity demonstrative willingness to deploy resources to get its way, unilaterally if need be (Nossal 1999, 3–4). In light of the large distance between the United States and the other major powers in a globalizing world, the apogee is not superpower but hyperpower. Having originated during a period of bipolarity to depict a split between two rivals, the category “superpower” is superseded by hyperpuissance (“hyperpower”), a term coined in 1998 by former French foreign minister Hubert Védrine to denote the reconstitution of the Cold War era and the astounding disparity in capacity between one actor and the others (Védrine 1998, as cited and elaborated in Nossal 1999, 2, 5; Vedrine 2001; Duke 2003; Nederveen Pieterse 2003; Vaïsse n.d.).

Like the term “hypercompetition,” the word “hyperpower” comes from both the policy community and scholarship: the WEF and university researchers in the first instance; the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and professors such as Amy Chua (2007) of Yale Law School in the second. 3 Offering a historical analysis of the handful of societies that have reached this extraordinary level, Chua equates hyperpower with world dominance. She hypothesizes that tolerance with respect to other societies is necessary for ascendance to hyperpower. Conversely, intolerance is associated with its demise (Chua 2007, xxv).

In my usage, “hyperpower” is distinct from “superpowers,” and is singular. There can be only one hyperpower, not rival or regional hyperpowers. Yet, as mentioned, hyperpower is more than state power, because it is diffuse and includes a network of overseas military bases and an assemblage of allies. In addition, hyperpower incorporates the ideological components of hegemony.

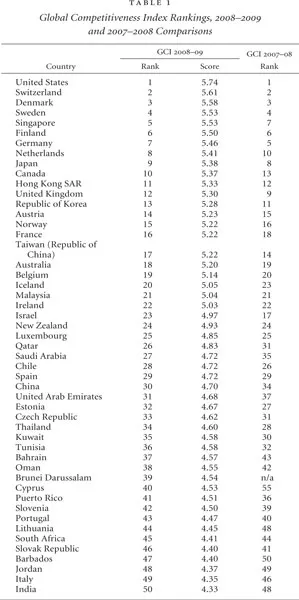

The amalgam of the world’s largest national economy, unmatched technological prowess, and a defense budget greater than that of the next twenty-five states is an unparalleled form of power (Adhikari 2004). The magnitude of this range is striking. The U.S. population is 4.6 percent of the world total and generates 28 percent of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP) (World Bank 2007). On the WEF’s Global Competitiveness Index 2008–2009, a model with twelve categories of measures applied to 134 countries, the U.S. economy again ranks number one in the world (World Economic Forum 2008). The categories are institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomic stability, health and primary education, higher education and training, goods market efficiency, labor market efficiency, financial market sophistication, technological readiness, market size, business sophistication, and innovation. On the basis of these indicators, Table 1 presents weighted averages of competitiveness by country. It is noteworthy that just ahead of Switzerland, Denmark, and Sweden, the United States scores well above the second and third largest national economies: Japan is in ninth place; China, thirtieth.

The United States leads in other crucial metrics as well. It is responsible for 38 percent of worldwide outlay on R&D (American Association for the Advancement of Science 2006). Fifty-seven percent of the U.S. share is military R&D (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD] 2006, 47).

In 2007, the United States alone accounted for 45 percent of total world military expenditure, almost as much as the rest of the global war chest. This percentage is slightly lower than in previous years due to the large rise of Eastern European spending, up 162 percent since 1998 (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute [SIPRI] 2008, 176–77). The U.S. figure takes into consideration the supplementary budget for the “war on terror,” which, by itself, is almost three times more than the entire military spending of each of the next four countries with the highest defense budgets—the United Kingdom, China, France, and Japan (SIPRI 2008, 177–85). What is more, according to Department of Defense data compiled through 2005, the United States maintains 737 military bases abroad. By comparison, Britain, in 1898, at the pinnacle of its imperial era, had 36 bases (Johnson 2006, 138–39). The U.S. military’s vast range is also reflected in the Defense Department’s figure of 761 “ sites,” though this inventory includes separate installations within single large bases and not (presumably) temporary facilities in Afghanistan and Iraq (U.S. Department of Defense 2008).

Notwithstanding this scope, it is important to avoid hyperbole. Hyperpower is neither unipolarity nor omnipotence. The discourse of unipolarity centers on the nation-state without capturing globalizing processes. Gauging ...