![]()

1

“The Customer Is God”

Women and China’s New Occupational Landscape

A host of interactive service jobs form a new occupational landscape for working-class women in China. Within this world of labor, the traits of youth, beauty, and deferential bodily dispositions constitute working-class women’s labor market value. Characteristics of the body (age, sex, height, weight, skin tone, comportment) are a now a basis for the segmentation of labor markets and also determine the length of a woman’s occupational lifetime in services. Service employers routinely dismiss workers as they approach their late twenties, when their physical beauty is thought to be diminished. To describe this state of affairs, working-class women invoke a subsistence metaphor, calling service work a “spring rice bowl” (qingchunfanwan). The popular phrase marks a stark contrast between the insecurity of present-day service labor (which is feminized and low-wage) and the Mao-era system of guaranteed lifetime employment, termed the “iron rice bowl.” Today’s service workers are deferent and feminized. Their mantra is “The customer is god.” This chapter traces women’s historical entry into labor markets in China and follows the evolution of their labor market participation through the Mao period (1949–1976) and the early reform era (beginning in 1978) to better understand the generation of young working-class women who have become China’s first modern service workers. The chapter also provides context for the empirical case studies ahead by describing the socialist institutional legacies that continue to influence the new service workplace by analyzing the salient features of the cities in which this research took place, as well as discussing the hotel industry in China and providing details about the hotels that are the subject of this study.

From Comrade to “Miss”: Women and China’s Shifting Worlds of Labor

A landmark achievement of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was allowing women to gain socially legitimate paid employment (Stacey 1983). Before the Communist Revolution in 1949, during the late Qing (1644–1911), a Confucian ethic prevented all but the most destitute of women from working in the public sphere. Women were confined to the household to prevent contact with nonfamilial males and thereby ensure the virtue of daughters and wives (Barlow 1994; Mann 1997; R. Watson 1986). Laboring outside the home transgressed standards of virtue and was associated with poverty. Until the early twentieth century, the vast majority of women who did venture out into the public sphere of paid employment were prostitutes and entertainers, work coded as immoral and indecent.

By the 1920s, Confucianism’s influence on social institutions began to erode, due in no small part to the nation’s inability to defeat British imperialism in the nineteenth century and Japanese colonialism in the twentieth century. In the 1920s, rural women poured into Shanghai to take up employment in the modern textile industry; in 1929 they made up 76 percent of the labor force in the Shanghai mills. These women continued to face public scorn for defying traditional gender boundaries and contended with violent harassment by overseers and local gangs.1 Not long after, women began to make inroads into service work. Teahouses in Chengdu, Sichuan, began hiring female waitresses to replace male workers who enlisted in the armed forces to combat Japan after its invasion of China in 1937. To protect the profession from the perceived indecency associated with women’s presence in the public domain, the union of teahouse workers established elaborate codes of conduct that required austerity of appearance and barred waitresses from wearing makeup, perming their hair, and flirting with guests (D. Wang 2008).

While some women made inroads into wage employment during this time, the vast majority continued to be confined to the household, where they performed familial duties based on kin roles such as wife, daughter-in-law, daughter, and mother-in-law, as prescribed by the Confucian classical texts. Within the household’s inner quarters, wives and daughters wove textiles that were sold by male kin at local markets and thus provided an important source of revenue for their families. The proceeds from the sale of these fabrics were used to pay household taxes (Bray 1997). Confining women’s labor to the household’s interior ensured that profits remained part of the patrilineal economy. Meanwhile, men circulated in the wider public sphere, laboring in fields, selling cloth and grain at periodic markets, and serving as functionaries for extended patrilineal kin networks, as well as the state civil service (Bray 1997; R. Watson 1986).

However, the Confucian ideologies that prescribed women’s household seclusion were subject to unrelenting attack by urban male intellectuals who were deeply committed to China’s modernization. They assailed China’s Confucian order, blaming it for the country’s weakness in the face of Western and Japanese imperialist domination. They targeted the gender and generational tyrannies at the root of Confucianism, arguing that confining women to the household and depriving them of education fundamentally weakened the Chinese nation. For these intellectuals, gender equality itself would form a basis for accelerating China’s modernization (Barlow 2004; Otis 1999).2 One important strain of this debate reasoned that educating women would strengthen their ability to raise strong and capable sons, which would in turn form the basis for enhanced national resilience. A host of others advocated for women’s full inclusion in all social institutions, regardless of their maternal status. One principle they all agreed upon was that the nation’s survival hinged upon eliminating Confucianism’s oppression of women.3

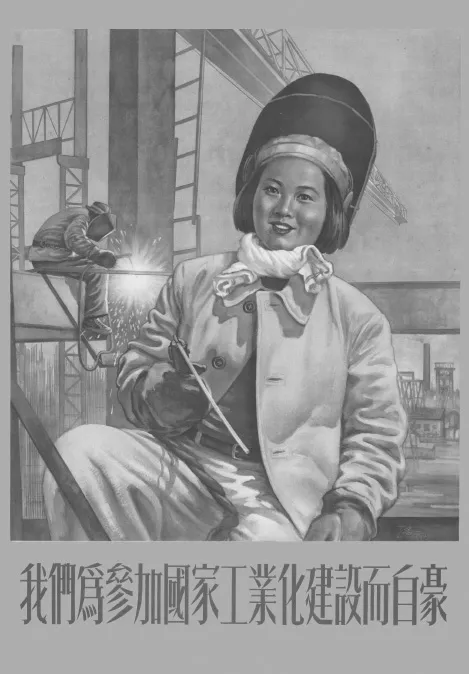

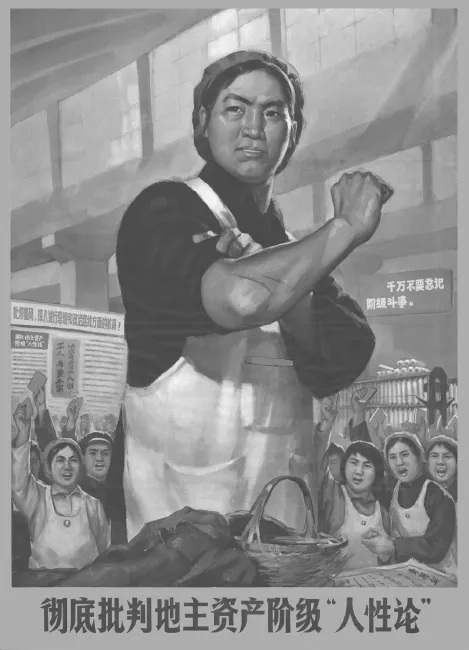

Many of the reforms proposed by these modern intellectuals were in fact adopted by the CCP after its ascent to power in 1949. Central to the CCP program was the recruitment of women en masse into wage labor. With this policy shift, women’s worth would no longer be tied solely to their role in the extended kin group. The CCP propagated a new socialist gender ideology that tied women’s respectability to the ability to support national development through productive, public labor (Stacey 1983; M. Wolf 1985). Along with these policy changes, the state invented a new iconography of “iron women” and “the first female” (nujie diyi), women who were the first to work in jobs such as welding, tractor driving, streetcar driving, and the like (Chen 2003). These icons were part of an effort to encourage women to radically alter their expectations for their life course. The six posters included in the pages ahead illustrate some of the representations and display the transformations in the bodily images of working-class femininity in China since the era of Mao Zedong. The first two images depict women in heavy industry and manufacturing who have attributes associated with proletarian masculinity. Figure 1 is a poster manufactured in 1954 and depicts a female worker recruited into the elite heavy industrial labor force as a welder. The caption reads, “We are proud to participate in the industrialization of the nation.” Another poster (Figure 2) features a militant female factory worker and proclaims, “Criticize feudal and bourgeois theories of human nature.” In these posters, women’s bodies are robust and large and communicate confidence. In Figure 2 the worker displays her muscularity in a threatening posture.

Although the majority of new socialist factories, rural communes, and service workplaces were highly sex segregated (Shu and Bian 2002; Walder 1986), women’s work was not “feminized”; in other words, women were not expected to exhibit characteristics traditionally associated with femininity on their bodies or in interaction.4 Managers strictly controlled women’s clothing and appearance to mute overt distinctions between men and women. In so doing, managers tried to protect working-women from accusations of immodesty for entering the public sphere of work, easing their transition into paid labor (Rofel 1999; Yang 1999). Feminine sexual expression was also thought to embody bourgeois values that weakened the proletarian principles of the party. The elimination of public displays of sexuality allowed the party to preserve its commitment to an ascetic order and avoid accusations of corruption (Evans 1997). By inducting women into a masculinized socialist proletarian sensibility, the CCP afforded them legitimacy and dignity at work as socialist subjects.5 Women who worked in the small service sector were subject to similar restrictions in dress and comportment.

FIGURE 1 “We Are Proud to Participate in the Industrialization of the Nation” (1954). From the International Institute of Social History/Stefan R. Landsberger Collections, http://chineseposters.net/themes/women-working.php (accessed May 3, 2011).

FIGURE 2 “Thoroughly Criticize the ‘Theory of Human Nature’ of the Landlord and Capitalist Classes” (1971). From the International Institute of Social History/Stefan R. Landsberger Collections, http://chineseposters.net/themes/women-working.php (accessed May 3, 2011).

In a regime that prioritized rapid industrialization, service was low-status labor. Consumption and services were thought to deplete productive resources while exacerbating status distinctions that the Mao regime sought to level. Moreover, the state eliminated the need for large retail, food service, or entertainment sectors by providing citizens with basic necessities and diversions through the urban workplace. A small consumer service sector supplemented workplace provisions. Products purveyed by these outlets were in high demand, and there was little incentive to promote them through warm, attentive, and smiling service workers. Instead, service workers acted more like gatekeepers of the meager array of consumer goods. As such they wielded a degree of power over customers (Verdery 1996). These workers were notoriously inattentive to customers. Yunxiang Yan describes staff in Mao-era China’s urban restaurants as “ill tempered workers who acted as if they were distributing food to hungry beggars” (2000: 210). One older woman I interviewed captured the spirit of service work in the Mao era as she reflected nostalgically on her prereform-era employment in a state-owned retail store: “At that time we didn’t even have to smile; we could yawn out loud and tell the customer to shut up, and no one cared.” Under the Mao regime, the notion that a worker might be paid to cater to or care about customers defied the egalitarian politics and sensibilities of the period.

During this time, even though expressions of femininity were minimized, party policies reproduced gender hierarchies. For example, the state formally recognized only husbands as heads of household (Stacey 1983). The party never questioned women’s responsibility for “second-shift” household labor; nor did it challenge the orthodoxy that every woman should marry and bear children (Evans 1997; Hershatter 2003). The segregation of employment by sex meant lower levels of remuneration for women workers, although all workers earned relatively low wages (Davis and Wang 2009). Moreover, the party perpetuated the norm that women should be the standard-bearers of sexual morality. In the workplace, women became the focus of concerns about sexual morality, and the regulation of their clothing was a measure to limit sexual enticement (Evans 1997). At the height of the state’s attempt at “gender erasure,” during the Cultural Revolution, female Red Guards were frequently subject to accusations of sexual impropriety.6 By incorporating women into labor, as well as limiting the accoutrements of “bourgeois femininity,” the party remedied some elements of gender inequality but by no means eliminated it.

The market reform policies of 1978 reversed the anticonsumption priorities of the Mao-era planned economy and with the reversal eliminated any vestiges of gender erasure. These reforms transformed China from a planned economy to a capitalist dynamo, in the process creating a massive urban service economy. One pillar of market transition was the division of land that belonged to agricultural communes, where workers had collectively farmed. This land, previously owned by the state, was distributed based on new long-term leases to rural households. In urban areas, state-owned factories first transitioned to partially or fully privatized businesses. Unable to compete with privately invested firms, most eventually closed their gates and furloughed millions of workers (Lee 2007). As result of these reforms, urban areas metamorphosed from focal points of industrial production to centers of consumer and producer services.

In a report delivered to the Ninth People’s Congress in 2002, then premier Zhu Rongji declared the necessity to stoke consumer demand: “We need to eliminate all barriers to consumption by deepening reform and adjusting policies. We need to encourage people to spend more on housing, tourism, automobiles, telecommunications, cultural activities, sports and other services and develop new focuses of consumer spending” (Zhu 2002). In the 2002 white paper on labor, the government declared that China’s tertiary industry, small and medium-sized enterprises and the nonpublic sectors of the economy, “shall be taken as the main channels for the enlargement of employment” (People’s Republic of China Information Office 2002: 8). The decline of urban manufacturing and the reorganization of rural production created massive labor surpluses that pushed women workers into the consumer service sector, where they became a growing underclass, laboring in insecure, often poorly paid work (Solinger 1999b). As the factories and farming communes that employed their parents ceased production young working-class women have taken up service labor in restaurants, retail stores, hotels, guesthouses, spas, bowling allies, karaoke bars, and clubs. They are China’s first modern consumer service workers.

Within this work they have undergone profound personal transformations. As the faces and voices of new service establishments, women workers are required to learn new forms of bodily and interactive deference. Employers routinely subject their fresh female recruits to strict new physical requirements. Women who aspired to be hostesses for the 2008 Summer Olympics were to be ...