![]()

1 The Political Economy of Regional Security in East Asia

Avery Goldstein and Edward D. Mansfield

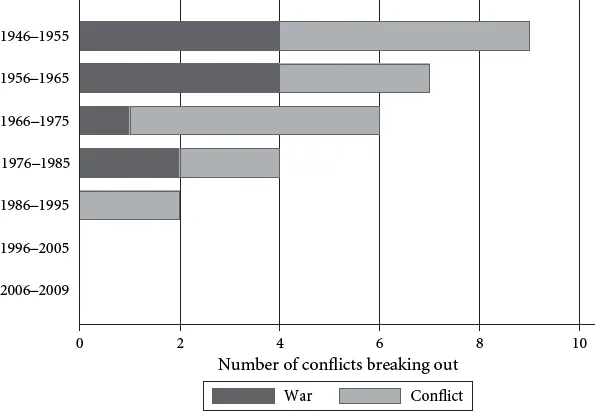

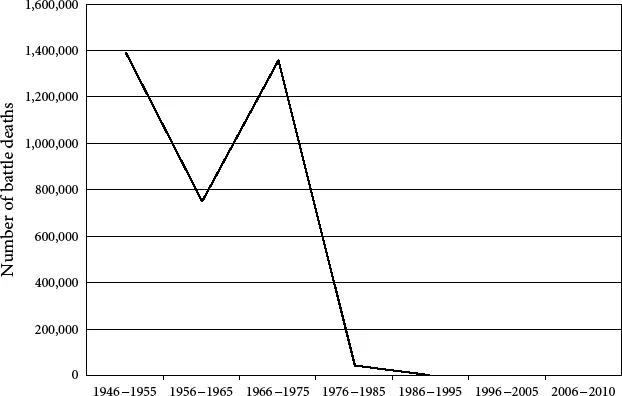

East Asia has experienced more than three decades of peace and prosperity, a sharp contrast with the recurrent wars and lagging development that plagued much of the region during earlier eras. The last major military conflict, the Sino-Vietnamese War, ended in 1979. Although skirmishes between the antagonists were not completely extinguished until the 1980s, the year 1979 marked the beginning of a clear secular decline in militarized conflict that has continued through the present (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2).1 That year also marked the start of sweeping economic reforms initiated under Deng Xiaoping’s leadership in China. China’s reforms, however, were only the most widely publicized among various efforts at economic liberalization throughout the region since the late twentieth century. These policy shifts have enabled many East Asian countries to share in a newfound prosperity that had previously taken root in Japan and in the so-called four tigers. Yet this era of peace and growth has been punctuated by periodic reminders of enduring security problems in the region. Do these security problems pose a threat to East Asia’s record of economic success? Or do economic success and the greater levels of international economic cooperation that have accompanied it provide a foundation for political cooperation and the management of security problems? The contributors to this volume shed new light on these important questions.

Three broad approaches to thinking about economics and security in East Asia can be identified. One approach views the region’s growing economic prosperity as a result of the peace that has prevailed. In an international setting fraught with fewer political tensions, nations could focus resources on domestic development and enjoy the fruits of international trade and investment with countries whose prosperity they no longer viewed through the prism of military rivalry. In this approach, what needs to be explained is the peaceful context that has provided the opportunity for economic activity to thrive. Explanations for this peace often point to the power and leadership of the United States. As the Soviet Union declined and then collapsed, the United States stood as the sole superpower. American preponderance not only mutes potential security rivalries among its allies but also serves as a hedge against future uncertainty over new military threats that might emerge. Consequently, East Asian countries can refrain from deploying the kinds of forces that they might otherwise need to cope with the possibility of conflicts with a resurgent Russia or an increasingly powerful China.

FIGURE 1.1 Onset of armed conflicts in East Asia, 1946–2009

SOURCE: Uppsala Conflict Data Program, Peace Research Institute Oslo, UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset, available at http://www.prio.no/CSCW/Datasets/Armed-Conflict/ (accessed August 23, 2010).

NOTE: East Asia = ASEAN+5 (China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan).

America’s relationship with China has also contributed to peace in the region. During the 1980s, Sino-American cooperation rested on a common interest in counterbalancing the Soviet Union’s assertive foreign policy. But even following the collapse of the Soviet Union, and despite the outbreak of some serious political and economic disagreements between China and the United States, the latter two countries managed to sustain a largely cooperative working relationship. Absent a common adversary, their overlapping interests in coping with problems of proliferation, terrorism, and the dangers of instability on the Korean Peninsula helped prolong a constructive U.S.-China relationship initiated during the closing decades of the Cold War. Although some analysts suggested that China’s rise would undermine Sino-American cooperation and perhaps jeopardize regional peace, the yawning disparity between Chinese and U.S. capabilities minimized concerns about the countries’ shifting power and enabled both states to focus mainly on the absolute, rather than the relative, gains they derived from bilateral cooperation. In short, one approach is to suggest that American power and the ability of the United States and China to avoid an adversarial relationship have sustained a peaceful international context conducive to regional economic prosperity.

FIGURE 1.2 Battle deaths from armed conflicts in East Asia, 1946–2009

SOURCE: Uppsala Conflict Data Program, Peace Research Institute Oslo, UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset, available at http://www.prio.no/CSCW/Datasets/Armed-Conflict/ (accessed August 23, 2010).

NOTE: East Asia = ASEAN+5 (China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan).

A second approach views peace as stemming from regional prosperity, or more accurately, from the economic activity that generates prosperity. The logic is discussed further below, but centers on the claim that interdependence between trade partners establishes benefits that would be scuttled in the event of military conflict. Participation in international economic institutions reinforces this constraint by clarifying these benefits and the associated opportunity costs of military conflict. Institutional participation also socializes elites to embrace transnational perspectives; in national policy debates, parochial perspectives are then less likely to prevail, thus facilitating the compromises that are necessary to sustain international cooperation and to prevent conflicts from escalating to the use of force. Aside from participation in international institutions, overseas commerce itself creates and sustains common interests between economic partners and encourages a more cosmopolitan perspective conducive to the peaceful adjudication of international disputes. Finally, economic exchange reshapes the domestic political landscape of the participating countries, thereby empowering those segments of society whose interests are served by a foreign policy that avoids disruptive military conflict.

A third approach is skeptical that peace in East Asia is linked to economic activity. As has often been noted, extensive economic interdependence and strong elite ties across the major European states in the early twentieth century failed to halt the slide to World War I. Other skeptics go further still and consider East Asia’s current period of peace and prosperity a brief respite from the normal pattern of interstate rivalry or perhaps even a mirage misleading analysts who fail to appreciate the looming dangers of military conflict and economic disruption. Such views typically draw on the Western, mainly European, historical experience and suggest that Asia’s future may well be Europe’s bloody past.

Even analysts who had become optimistic about Europe’s peaceful future in the immediate aftermath of the Cold War argued that the basis for such optimism was absent in East Asia. Multilateral institutions that evolved in Europe over the era since World War II had provided a trellis first for economic and then for security cooperation that had no parallel in East Asia. In the early 1990s, Aaron Friedberg (1993–1994: 22) famously drew a sharp contrast between the “rich ‘alphabet soup’” of regional organizations in Europe and the “thin gruel” of such organizations in Asia. Moreover, Europe had forthrightly addressed many troubling historical legacies that had repeatedly generated conflict on the continent, as well as more recent sources of antagonism. By contrast, East Asia seemed a region still rife with such problems—competing territorial claims, divided states, and lingering historical grievances (especially toward Japan), all fueled by the heated nationalist sentiment of newly emerging, newly independent, or recently reviving states. For those subscribing to this dark vision, East Asia’s story of economic prosperity was not just about rising living standards; it was equally about the accumulation of national resources that would sooner or later fuel military capabilities harnessed to competing national interests.

Such concerns notwithstanding, East Asia’s peace and prosperity endures. If the existing evidence remains inconsistent with the pessimists’ expectations, is that because their theories about the links between economics and security on which they base their predictions are flawed? Are there assessments of East Asia that are more solidly grounded in theories that identify connections between economics and security? More generally, how useful is the existing tool kit of international relations theories for explaining East Asia’s recent peace and prosperity?

Any particular theory explains only a slice of reality by setting aside many of the details and some of the causes that produce observable outcomes. A more comprehensive understanding of historical or contemporary events requires tapping various theories and the partial insight that each offers. Consequently, when the authors of the chapters in this volume examine the nexus of economic and security relations in East Asia, they usefully draw on a rich variety of theoretical approaches that can illuminate important questions about a region whose significance for students of both international political economy and international security has grown dramatically over the past thirty years. Their work suggests, in various ways, that the interaction of economic and security concerns defies simply categorizing either as the independent variable (cause) and the other as the dependent variable (effect). To grasp the reasons for, and evaluate the durability of, East Asia’s recent peace and prosperity, both economic and security fundamentals matter; the chapters here explore how they matter and, where possible, the extent to which existing theories explain why.

The remainder of this introduction provides some general background for the more focused chapters that follow. First, we set forth evidence that demonstrates the growth of economic regionalism in East Asia, comparing the current era with the recent past in the region and drawing some limited comparisons with evidence from the European experience. Second, we clarify the security issues whose links with regional economic developments our authors examine. Third, we briefly discuss leading theories that claim to offer explanations for the connection between economic and security affairs in international politics. Fourth, we discuss the prominence of China in many of the chapters, even as the volume addresses East Asia as a region. We conclude by describing the organization of the volume and by offering a preview of the perspectives in the chapters that follow.

The Growth of Economic Activity in East Asia

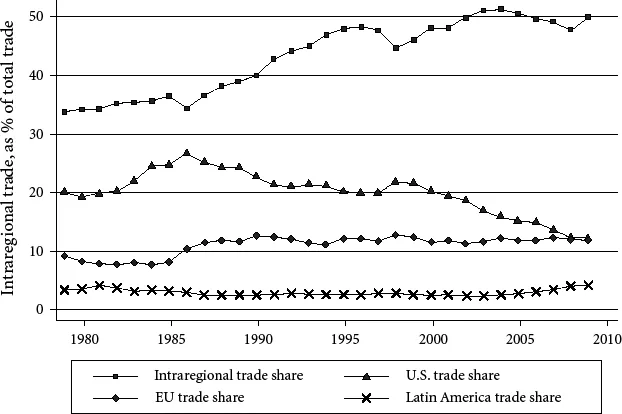

Over the course of the past thirty years, there has been a substantial rise in the amount of cross-border economic activity in East Asia. To illustrate this growth, we present some data drawn from the economies in East Asia: the ten Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) states (Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam), China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Figure 1.3 shows the ratio of international trade among these countries to the total trade that they conducted for each year from 1979, when economic reform started gaining traction throughout the region, until 2009.2 In 1979, roughly one-third of the trade these states conducted was intraregional, a value that spiked to about one-half by 2009. China has played a leading role in this rise. In 1979, about 10 percent of intra–East Asian trade stemmed from foreign commerce involving China; by 2009, the value exceeded 30 percent.

Figure 1.3 also reports the annual flow of trade from East Asian countries to the United States, the European Union, and Latin America, respectively, as a percentage of the total overseas commerce conducted by East Asian states. Clearly, the surge in intra–East Asian trade is not matched by East Asian trade with other key partners. States in the region have experienced no noticeable change in the amount of foreign commerce with the European Union and Latin America. Over the past decade, they have experienced a rather pronounced dip in trade with the United States.

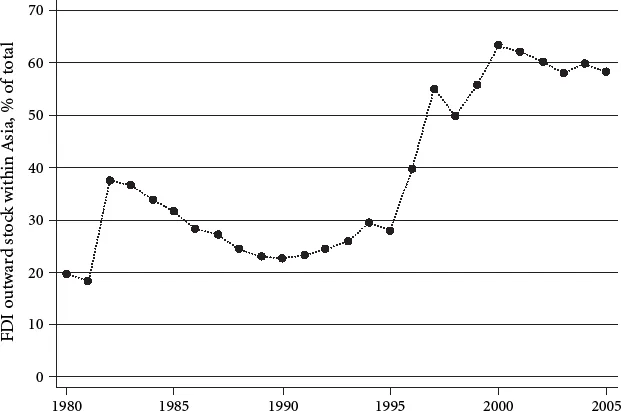

In addition to trade, foreign direct investment (FDI) within East Asia has risen precipitously. Figure 1.4 shows the yearly stock of FDI emanating from East Asian home countries and located in host countries in the region as a percentage of total outward FDI by East Asian states. There is ample evidence that, over the past three decades, these states have located an increasing amount of their foreign investment within East Asia. Indeed, the percentage of total outward East Asian FDI located in the region tripled, rising from about 20 percent in 1980 to roughly 60 percent by 2005.

FIGURE 1.3 Trade within East Asia and trade between East Asia and the United States, the European Union, and Latin America, 1979–2009

SOURCE: International Monetary Fund’s Direction of Trade Statistics.

NOTE: East Asia = ASEAN, China, Korea, Japan, and Hong Kong. These figures do not include Taiwan because it is not possible to obtain reliable data on Taiwanese trade before 1990.

Over the past thirty years, there has also been a dramatic increase in the number of economic institutions designed to promote and regulate trade, investment, and finance in East Asia. Only a few such institutions existed in 1980; currently, there are a few dozen. Moreover, plans are afoot to launch even more. China, Japan, and South Korea have each explored the possibility of forming a free-trade area (FTA) with members of ASEAN, the region’s most important institution. Various East Asian countries have expressed interest in concluding a regionwide free-trade zone that would encompass not only China, Japan, South Korea, and ASEAN, but also Hong Kong, and Taiwan. More generally, policy makers throughout East Asia have commented on the desirability of forming additional economic institutions in the region. In 2005, for example, Indonesian Finance Minister Jusuf Anwar commented that East Asian integration should be promoted by “weaving a web of bilateral and multilateral FTAs” (Nikkei Weekly 2005).

FIGURE 1.4 Annual stock of FDI from East Asian home countries to East Asian host countries as a percentage of total East Asian FDI, 1980–2005

SOURCE: Collected and compiled by Witold Henisz at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, from the UN Conference on Trade and Development and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

The growth in economic activity within East Asia is impressive, even when compared to Western Europe, which sets the standard for regional economic integration. As shown in Table 1.1, both East Asia and the European Community (EC/EU) doubled the amount of intraregional trade as a percentage of total trade between 1960 and 2009.3 To be sure, in any given year, the ratio of intraregional trade to total trade was anywhere from 10 percent to 60 percent greater for the Western European countries than for the East Asian states. Moreover, the value of total trade and intraregional trade conducted by EC/EU members far outstrips that conducted by East Asian states. N...