![]()

PART ONE

The Secret Denunciation

What are the reasons that justify secret accusations and punishments? Public safety, security, and maintaining the form of government? But what a strange constitution. . . . Can there be crimes, that is, public offenses, of which it is not in the interest of everyone that they be made a public example, that is, with a public judgment?

—Beccaria, On Crimes and Punishments

![]()

ONE

The Parish Priest

On September 2, 1785, Bortolo Fiorese, a priest at the church of Sant’Angelo in Venice, penned a secret denunciation to the Venetian government: “Yesterday I went to the apartment of Signore Gaetano Franceschini, a resident of this parish, and removed from that apartment, in the absence of the master, a girl of about eight years, Paolina Lozaro by name, and I delivered her into the hands of her mother Maria. I was driven by the reports I had obtained about the bad reputation and depraved inclinations of Signore Gaetano, and about his keeping the girl, the night before, scandalously in his own bed.”1 That same day, in immediate response to his denunciation, Father Fiorese was summoned to the Doge’s Palace for questioning before a tribunal of the law. So began the legal investigation of Gaetano Franceschini in a case that would claim the attention of the Venetian judicial system for the rest of the year. A tribunal of four duly elected Venetian patricians fulfilled their civic responsibilities by overseeing the interrogation of an entire neighborhood in an attempt to determine exactly what happened to Paolina Lozaro during a single night in the home of Gaetano Franceschini before Father Fiorese removed her from the premises.

It all began on the last day of August, in the middle of the morning, according to Father Fiorese. “I happened to be in the sacristy of my church, and a woman wearing a silk shawl approached me and called me aside, and told me the following story. She said to me that she had just that moment come from confession.” The woman in the silk shawl introduced herself to the priest as the housekeeper of Signore Gaetano Franceschini and confided that her master had recently made her an alarming proposition. The housekeeper, a recent widow, had two young daughters who were being raised outside the city, since their mother had to live as a servant in her master’s house. Franceschini had suggested that he might employ one of the daughters in his household as well, especially since he had recently received some very particular medical advice: “He had been advised to find a young girl [una tenera ragazza] to sleep with him so that her warmth might reinvigorate his own.” Not in the least deceived by this medical “pretext,” the housekeeper declined the proposition and kept her daughters in the country, but she herself continued to work in Franceschini’s service.2

This morning, however, as she told Father Fiorese, her master had ordered her to go to the church of Sant’Angelo where she was to meet a certain Friulian woman, a Furlana, with a young daughter. The housekeeper had no trouble recognizing the Furlana, who was lingering there in the church with her daughter and was obviously waiting to meet someone. Father Fiorese, testifying before the tribunal, explained the housekeeper’s dilemma and his own reaction to her story.

She was to meet a Furlana with a girl, and to bring the girl home, as a substitute for her own daughter to have with him in bed. She found the Furlana and the girl right there in the church, but, feeling herself constrained by the obligations of virtue and religion, she invoked my advice and assistance. Having heard about this interesting matter, I did not however believe that I should immediately give complete credence to the story, especially since the suspicion occurred to me that this woman actually wanted to put forward her own daughter and was seeking by this means to deprive the other girl of her good fortune [provvidenza]. Nevertheless, I took the expedient of advising that woman to go home and tell her master, of whom she seemed frightened [dimostrava soggezione], that she had not found the Furlana.3

The silk shawl was known variously in Venetian as the zendale, the zendà, or the zendado. It would probably have been black in eighteenth-century Venice, worn over the head, wrapped around the body, perhaps even partly covering the face, if a woman, for one reason or another, wished to conceal her identity. This woman, Franceschini’s housekeeper, must certainly have hoped for some discretion as she revealed her master’s intentions to Father Fiorese.

The priest immediately perceived the sinister aspect of the situation—that is, the recruitment of a warm young body—but nevertheless his first suspicion was directed against the housekeeper herself rather than her master. Even though Father Fiorese seemed to understand perfectly well that little girls should not be employed to reinvigorate old men in bed, he also had no doubt that for a girl from the lower levels of Venetian society it would be a piece of good fortune to be taken into the service and under the protection of a prosperous older gentleman. The housekeeper presented herself to the priest as reluctant to play the part of a procuress, professing to be too troubled to follow through on her master’s order, but the priest thought she might be merely trying to procure the position for her own daughter by obstructing the other girl’s opportunity with a smokescreen of sexual insinuations.

“Donne veneziane in zendà.” Venetian women wearing black silk shawls, like that of Maria Bardini the housekeeper. From Pompeo Molmenti, La storia di Venezia nella vita privata.

Father Fiorese did not seem amazed at the brazenness of proposing to use a young body to warm an old one, and it may have seemed even unremarkable to a man who knew something about sinners in eighteenth-century Venice. If he was familiar with the Bible, which was not particularly likely for a Catholic priest at that time, he might have recalled the precedent of King David: “Now king David was old and stricken in years; and they covered him with clothes, but he gat no heat. Wherefore his servants said unto him, Let there be brought for my lord the king a young virgin: and let her stand before the king, and let her cherish him, and let her lie in thy bosom, that my lord the king may get heat.” In the end, they delivered a virgin, who “cherished the king, and ministered to him: but the king knew her not.”4 Eighteenth-century medical notions still involved a significant measure of popular superstition, including an accumulated traditional wisdom about age and youth, heat and cold, health and debility, sex and virginity. At the same time, Venice in the eighteenth century was enlightened enough for a parish priest and a conscientious housekeeper to agree that the medical pursuit of a young girl’s bodily warmth was surely the “pretext” for unspoken predatory intentions.

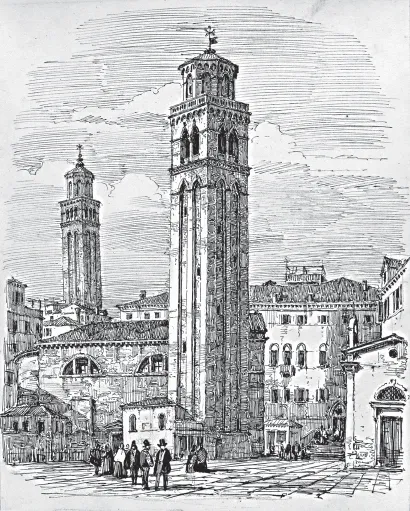

Church of Sant’Angelo with Campanile, in Campo Sant’Angelo. The engraving shows the campo before the demolition of the church and its bell tower in 1837. The leaning tower of San Stefano is visible in the background. From Souvenirs de Venise (1836), by Giovanni Pividor. By permission of the Biblioteca del Museo Correr, Venice.

The urban landscape of Venice today is not altogether different from that which Father Fiorese inhabited in 1785. Many of the churches of his day still survive with their treasures of sacred art, but the church of Sant’Angelo does not. Dedicated to the Archangel Michael, the medieval church of Sant’Angelo was demolished in 1837, so today the Campo Sant’Angelo preserves only the memory of the church in the name of the square. The Campo Sant’Angelo lies between the Accademia bridge and the Rialto, a busy space in the heart of Venice; two beautiful Gothic palaces with delicately pointed arches at the windows, Palazzo Gritti and Palazzo Duodo, face each other across one end of the square.

Campo Sant’Angelo today, without the church and its bell tower. The leaning tower of San Stefano still stands in the background

In the eighteenth century the church of Sant’Angelo was known to contain Titian’s last painting, the Pietà (1575), at one of the altars—but the painting is to be found today in the Accademia museum.5 The Pietà shows the Virgin Mary with the body of Christ in a painted architectural niche, while Nicodemus kneels before them, and Mary Magdalene, one hand raised, seems to be stepping out of the painting toward the viewer—into the church of Sant’Angelo. The Titian Pietà would have been very familiar to Father Fiorese. It would certainly have been present in his church on that last day of August in 1785, the day that he received the unusual confidence of the woman in the silk shawl.

Having sent her away, Father Fiorese turned his attention to the Furlana and her daughter. The Furlana was Maria Lozaro, an immigrant from Friuli in the city of Venice. Friuli was a province of the Venetian Republic northeast of Venice, at the head of the Adriatic gulf, adjoining the Austrian and Slovenian provinces of the Habsburg monarchy. Within the Venetian state Friuli was also a border region between Venice’s mainland Italian territories and the subject lands of the eastern Adriatic shore, Istria and Dalmatia, with their extensively Slavic populations. In the metropolis of Venice there was a significant immigrant population from Friuli, usually poor and often looking for employment in domestic service or menial labor. Friuli and the Friulians had a distinctive history and regional character. A Furlana would have spoken the regional Friulian language as her native tongue and would even perhaps have been characteristically dressed in provincial costume.

To someone like Father Fiorese, a native Venetian, Maria Lozaro was a humble provincial subject of Venice, ethnically distinct in her Friulian extraction, and he designated her simply as the Furlana.

I called aside the Furlana, who was already in the church, and asked her the reason for which she was there. She replied to me that an older gentleman—though she didn’t know who he was—had sought out her daughter, to keep her with him as an adoptive daughter [come figlia d’anima], and had promised to pay her a daily wage corresponding to eight lire monthly, for which reason he was coming to meet the girl, and the mother was waiting for him to come and take the girl away as agreed. I then tried opportunely [destramente] to get her to reflect, by telling her that entrusting a girl to someone she did not know could be too risky [troppo azzardo], that the excessively advantageous offer should have given her some well-founded suspicion, and that I too had some inkling of that sort. And so therefore I advised her for the moment to remove herself to the nearby church of San Stefano, and I would come half an hour later to tell her something more definite, since just then I could not go, since I had to deal with another interesting matter—which was in fact true. My intention then was to increase her suspicions in such a way as to make her distance herself for that day, so as to preserve the secrecy of the other woman who had confided in me, and so I would have time to understand the matter properly. The Furlana was persuaded to leave, from which I recognized the innocence of her readiness to abandon her young daughter, and she headed toward San Stefano.6

If Father Fiorese’s first suspicion was that the woman in the silk shawl was trying to obtain the position for her own daughter, his second suspicion was that the Furlana was no less eager to seize upon this good fortune. By leaving the church, and thus forgoing the rendezvous, she proved her “innocence” to him. Father Fiorese had clearly contemplated the guilty possibility that, in order to attain such good fortune as a wage of eight lire monthly, the Furlana might have been perfectly willing to install her young daughter in the old gentleman’s bed. Suspicious of the housekeeper, suspicious of the mother, the priest was also, but not yet extremely or exclusively—suspicious of the gentleman himself, Gaetano Franceschini.

All through the priest’s account of this episode in the church of Sant’Angelo, one person present in the church remained strangely invisible. Maria Lozaro must have been accompanied in the church by her daughter, the eight-year-old girl who was the object of all concerns and the reason for all suspicions. Yet Father Fiorese made no remark whatsoever about her age or appearance or demeanor, gave no clue as to whether the child seemed frightened or cheerful or bored or preoccupied. By the time Father Fiorese saw her again, she would have spent a night in Franceschini’s bed, and the priest would have much more reason to be concerned about her. For the moment, however, he had some other “interesting matter” to attend to, and his mere half an hour of other business was going to prove to be all the time that was needed to precipitate the disaster of which he claimed to have an inkling.

The walk from the Campo Sant’Angelo to the Campo San Stefano takes only a matter of minutes, as they are almost adjacent squares. San Stefano is not a small church, and Father Fiorese might have had to spend a few minutes looking for the Furlana inside, in the magnificent Gothic structure with its Venetian celebrity tombs of the sixteenth-century composer Giovanni Gabrieli and the seventeenth-century military hero Francesco Morosini. The priest might even have noted the modern, that is, eighteenth-century, painting of The Massacre of the Innocents by Gaspare Diziani. The innocent child of Maria Lozaro, however, was not there in San Stefano. Father Fiorese had had half an hour to reflect upon the situation and may have now felt prepared to say “something more definite,” but mother and daughter were nowhere to be found.

The church of Sant’Angelo defined a parish and marked the center of a Venetian neighborhood in which Father Fiorese, as the parish priest, would have been an important figure, occupied with many strands of church and community business.7 His failure to find the Furlana in San Stefano seems not to have alarmed him immediately, and he probably put her problem out of his mind as he continued with his parochial responsibilities. Later that same day, however, Father Fiorese was taking a coffee break from his business when he encountered Maria Lozaro again, this time without her daughter. “Having retired nearby to the coffeehouse, to chat with someone, I saw the Furlana approaching, agitated.” She told him what had happened earlier in the day, how she had left the church of Sant’Angelo intending to go to San Stefano, as he had suggested, but Gaetano Franceschini had been waiting for her in the Campo Sant’Angelo as she came out of the church. Maria Lozaro was surprised to see him: “and being frightened [per soggezione], did not have the courage to avoid being led home by him.” She was already anxious after Father Fiorese’s warning, and she still did not know Franceschini’s name. Franceschini, however, having brought her to his apartment, tried to be reassuring and made various promises in order to get her to leave the child with him, “suggesting however that the Furlana should instruct her daughter to obey him in everything, and advising her that she not come back to see the girl until the following Sunday.”8 In fact, Franceschini lived just upstairs from the coffeehouse, in the same building, and the girl was in his apartment at the very same time that Father Fiorese was chatting and drinking coffee below.

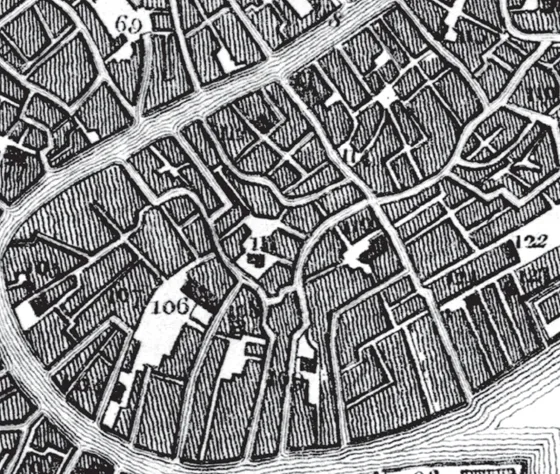

Neighborhood of Sant’Angelo: number 111 shows the Campo Sant’Angelo with the church in the middle of the Campo; number 106 shows the adjoining location of San Stefano; number 122 shows Pi...