![]()

1

The Competitive Dynamics of Citizenship and Immigration Policy

Verónica is a newly minted architect living in Mendoza, a city on Argentina’s Andean border with Chile. She is twenty-four years old at the time of our 2004 interview and married to Cacho, a technician in the oil industry. Verónica is more than a year into the process of applying for papers so that she and Cacho can emigrate in search of better opportunities. Possible destinations include Fort Lauderdale, where Verónica has an older sister married to an American, or Barcelona. Cacho has spent time in the United States and does not like the lifestyle there. Verónica thinks it more likely that she will be able to work in her chosen profession if she and her husband migrate to Spain, where they would encounter fewer linguistic and institutional barriers. An Italian or Spanish passport would allow the couple to move to Barcelona, and Verónica has decided to “get an Italian passport” in view of her ancestry and the nationality laws of that country. She smiles as she recalls how easy she had thought the application process would be, given the number of Italians in her family tree.

However, getting an Italian passport has proved to be a complicated project. Verónica has spent a night outside the Italian consulate with her younger sister seeking to learn from consular officials what documents she needs to prove her grandparents’ citizenship, where she can find them, and how to translate and certify them. In line at the Italian consulate, she learns from other applicants about the obstacles to getting required papers from Argentine government offices and Italian comunas, as well as shortcuts in the bureaucratic procedure of applying for Italian citizenship. After months of speaking to her parents, her sole surviving Italian grandmother, and other relatives who might have relevant information or papers to support her application, she now sees clearly that the process will be convoluted. Her Italian grandmother cannot transmit her citizenship because she married a Spaniard in the early 1940s.1 No one seems to know the whereabouts of her deceased parental grandparents’ personal documents. Verónica thinks she has succeeded when she discovers that some cousins have visited her grandparents’ village in Italy and obtained birth certificates for them. The cousins, however, are unwilling to share these documents because they are involved in a legal battle over family property in Italy. A great aunt offers some family papers that turn out to be useful for the application procedure. Verónica writes her grandparents’ comuna and gets a missing birth certificate. Almost eight months after initial queries, she files a completed application.

Six months later, she learns that the consular mail service has lost her application. Verónica is disheartened because a new submission will require another set of original documents. She decides to pursue another avenue to European citizenship when she learns that one of Cacho’s grandparents was a Spanish immigrant from Galicia. Cacho’s sister has collected the necessary papers and submitted an application for Spanish citizenship. Verónica plans to take advantage of this documentation and will have Cacho act as the main applicant. Verónica would then be eligible for Spanish nationality based on marriage. She would have preferred Italian citizenship because it can be held in Argentina and does not require travel within a year as the Spanish procedure does. In a follow-up contact several months later, I learn that Cacho’s sister and brother-in-law have received their resident’s permit and are already living and working in Valencia. Verónica and Cacho are scheduled for interviews at the consulate.

I am struck by Verónica’s pragmatic and detached account. She makes no mention of affective ties to her ancestral homeland; she moves effortlessly between talk of Spanish, Italian, and European Union citizenship. Before this application procedure, neither she nor Cacho had ever shown interest in the homeland of their grandparents. They speak no Italian or Galician, have not participated in immigrant regional or cultural associations in Argentina, and until recently had only a vague sense of their grandparents as immigrants. Verónica’s narrative is primarily about gaining access to better opportunities in Spain or Italy. There is no indication in our conversation that her sense of being an Argentine is in any way threatened by having a second nationality.2

Verónica’s story raises critical questions about the history and quality of citizenship in major countries of immigration and emigration. How is it possible that she has access to the citizenship of her ancestors from another country or even to that of her husband’s forebears? Why do these options not affect her sense of Argentine nationality? How is it that she can gain a legal tie to another country without having any affective links to it? More broadly, why do some countries attribute nationality based on where a person is born—like the jus soli policy of Argentina—while others do so according to the nationality of a person’s family, like the jus sanguinis policy of Italy? Scholars ask questions infrequently about the quality and history of legal citizenship, and yet answers to these questions suggest that this institution is not unchanging, as nationalists would have us believe, but rather the result of struggles within and among state actors to determine who can belong to their organizations. While states have changed citizenship for strategic reasons, subsequent changes are constrained by the manner of its institutionalization. In turn, this institutionalization can have repercussions for participatory and affective citizenship, as I show in Chapters 3 and 4. By historicizing citizenship, we learn a great deal about the state: as an organization it has had a variable and uneven capacity to control material and symbolic resources, to determine membership status, and to guarantee members’ access to these resources.

In this book I argue that that the strategic forces that shape patterns of citizenship have had the secular effect of making variable the link between individuals and states, even as nationalists maintain that this link is unchanging and exclusive. Citizenship matters because changing the quality of people’s link to the state also modifies people’s relationship to the nation, civil society, and markets. In this chapter, an analysis of Argentina, Italy, and Spain’s scramble for migrants and citizens reveals the dynamics that have shaped nationality policy, facilitated plural memberships, and set the stage for a reconfiguration of citizenship. Drawing on historical materials, migration data, laws, and jurisprudence from each country, I argue that Italy, Spain, and Argentina have developed birthright and descent patterns of citizenship law and preferential immigration policies due to the forces at work in a political field in which they jockeyed to gain legitimate control over the same population of migrants and their children during periods of state formation and consolidation. The competitive dynamic is driven by responses to the dilemmas posed by making nationals in a context of highly mobile populations. To make this argument, this chapter examines (1) trends in this Atlantic migration system during critical periods of state formation and consolidation before and after the First World War, (2) the dilemmas these trends posed for nation-state makers, and (3) the legal and organizational strategies used by these countries in the scramble to gain the formal and affective allegiance of migrants and their children.

Standard accounts of nation-state building in Argentina, Italy, and Spain generally focus on the domestic processes by which state agents make populations available for official administration and culturally integrate individuals into a national collective. The first process has focused on the legal definition of individuals’ status relative to the state and on their identification. The second process has entailed multiple organizational efforts to implement legal definitions of citizenship and to inculcate a sense of belonging to a nation. A relational reading of the evidence presented below demonstrates that these processes have happened in a field of politics that spans domestic and international arenas. State actors fashioned citizenship and migration policies anticipating and reacting to similar policies in other countries. Their awareness of others’ moves has translated into specific practices meant to challenge and assert legitimate control over migrants against other states’ claims. These legal-organizational practices constitute a dynamic of competition over jurisdictionally mobile people that shaped patterns of political membership and belonging. The citizenship alternatives of Verónica and Cacho exist, in other words, because Italy and Spain designed nationality laws and practices to keep ties to their grandparents and to them even as Argentina sought to call new arrivals their own.

The emphasis on interstate dynamics may give the impression that migrants and their descendants have been passive subjects of top-down nationalizing initiatives and that they lack “agency.” They have not and they do not. Migrants have shown their agency as they have tried to circumvent, undermine, or subvert states’ efforts to control their movement and membership.3 New arrivals in Argentina regularly made fraudulent claims to gain citizenship, avoid military service, and access police or other government jobs reserved for Argentines (Álvarez 1912). Spanish and Italian migrants who returned to the homeland claimed to be Argentines to avoid legal obligations in their countries of birth. Migrants left from European ports that were likely to have laxer paper controls (Roudié 1985). Migrants used counterfeit papers or used real papers fraudulently. Two Spanish emigrants in the 1870s, for example, caused a flurry of official correspondence when they traded documents to travel between Buenos Aires and La Coruña (López Taboada 1993). The practice had become so common that Spanish theater mocked the ease with which a young man could use an older person’s paper (Moya 1998). Today, would-be Argentine emigrants like Verónica and Cacho push the limits of nationality and immigration procedures armed with higher social and human capital than was available to their Italian or Spanish forebears.

The examples cited suggest a larger point about agency that, though obvious, is often lost in contrived debates about whether or not people “have” the ability to make choices. Agency is a complex concept and is constituted in particular sets of situated relations (Emirbayer and Mische 1998; Jasper 2006). It is not a discrete, unilateral characteristic of individuals, nor is it absolute. Migrants of the past had a range of options open to them, including the very act of emigrating, but economic, political, and cultural factors made and constrained these options. Once individuals decided to leave their country of origin, states had considerable influence on the conditions under which they could do so. Even when migrants circumvented state controls, they did so on terms set by official rules. They did not, for instance, shun documentation altogether, but rather they got fake documents or used somebody else’s papers. The state’s creation of legality—itself an organizational and ideological achievement—underlay the possibility of illegality (Cook-Martín 2008; cf. Noiriel 1996, 59). The upshot for my argument is that state and individual influence on citizenship and its implementation have been mutually constituted and that, even when a powerful organization like a national state sets the menu of options for persons under its influence, individuals find ways to advance their agendas. This mutual influence is the result of competing state efforts to control people; their efforts may, through conflicting demands, create spaces in which individuals have more citizenship options than they might otherwise.

Dilemmas of Nation-State Making in an Atlantic Migration System

Building nation-states has historically involved the construction of geographic, political, and symbolic borders to enclose a population of citizens. From the perspective of the architects and builders of a nation-state, populations should more or less coincide with these borders. In addition to the usual challenges of constituting national populations, Spain, Italy, and Argentina faced the dilemma of how to make nationals of people who moved among their territories.4 The migration of actual or potential nationals put states in the predicament of balancing the material and symbolic costs and benefits of migration. These dilemmas changed over time, but those confronted in the five decades preceding the First World War were especially significant because they shaped the institutions that subsequently regulated migration and nationality. The resolution of these dilemmas brought Argentina, Italy, and Spain into a competitive arena where they used legal and organizational tools to embrace as their own the same group of mobile people and their children.

Emigration States: Italy and Spain

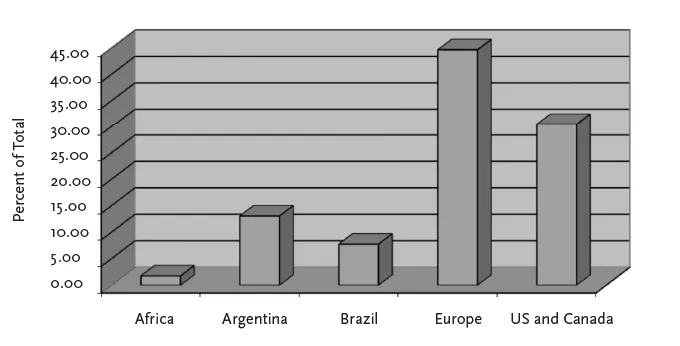

Nation building in Italy and Spain was complicated by the substantial emigration that was occurring at the time. Shortly after Italy’s Unification in 1861, there were already statistical reports of Italians abroad. Argentine official statistics began tracking “Italians” in 1857, five years before Italy existed as an official political and unified entity.5 The 1861 Italian census reported four hundred thousand Italians outside the kingdom and a decade later census takers counted a million absent Italians (Gabaccia 2003). Between 1876 and 1914, 14 million Italians left for other European countries, North America, the River Plate region (Argentina, Southern Brazil, and Uruguay), Northern Africa, and a smattering of other places (Figure 1.1). While favored destinations included core European and North American countries, a significant proportion of Italian migration between 1876 and 1925 went to developing peripheral countries, primarily Argentina and Brazil. Italian political elites saw these countries not as peers in the periphery but as targets for commercial and demographic colonization and thus potentially part of a più grande Italia, or Greater Italy (Carpi 1874; Einaudi 1900; Sori 1979,127; Regno d’Italia 1926; Regno d’Italia, Direzione Generale della Statistica 1884; República Argentina 1925; Virgilio 1868).

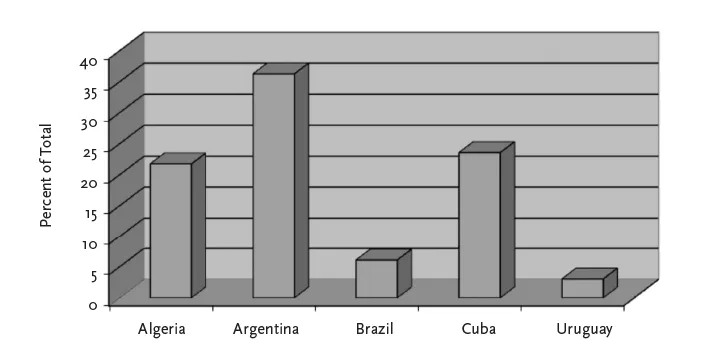

Mass emigration from Spain started later than in Italy, but for similar demographic, political, and economic reasons. Migrants from different regions showed preferences for specific destinations. Between 1885 and 1920, about 3.2 million Spaniards left for the Americas (75 percent), Africa (19 percent), Asia/Oceania, and the rest of Europe (a movement which even accelerated during the First World War) (Figure 1.2). Of those who migrated to the Americas, most went to Argentina, Cuba, and Brazil. Argentina was a preferred destination for early Basque and Catalan migrants and later Galicians, while Cuba was a destination favored by Canary Islanders. By the early 1920s, a well-established migration network linked Spain to main destination areas. Despite their rural origins, Spaniards settled disproportionately in cities, where they worked in the growing service and merchandising sectors as well as in crafts. Spanish streams included more women than did the Italian flows and showed a greater propensity to settle abroad (Moya 2003; Sánchez Alonso 1995; Yáñez Gallardo 1994). Spanish and Italian migration patterns to Argentina differ in ways that may account for the intensity with which each country engaged Argentina’s nationalizing efforts. First, the absolute number of Italians migrating to Argentina was earlier and much greater than that of Spaniards. Argentina was one of several destinations for Italian emigrants, while it represented the main destination of Spanish emigration, followed by Cuba and Brazil. Second, available data suggest that on average Italians emigrated with the aim of return, while Spanish emigrants had more permanent objectives (see Table 1.1) (Gabaccia, Hoerder, and Walaszek 2007; Sánchez Alonso (1992); República Argentina 1925; Beyhaut 1961, 43–44; Nascimbene 1994).

FIGURE 1.1 Main Destinations by Percentage of Total Italian Emigration, 1876–1925

SOURCE: Regno d’Italia 1926

NOTE: These destinations represent over 98 percent of all Italian emigration during this period (total emigration 16,629,879).

Immigration Nation: Argentina

Beginning in the 1860s, Argentina experienced unprecedented economic and social transformations. This formerly “poor and forgotten” backwater of the Spanish Empire saw its per capita GDP increase by 64 percent between 1870 and 1890, and by 28 percent in the last decade of the nineteenth century (Vázquez-Presedo 1974, 30; Maddison 2003). Between 1900 and 1912, per capita GDP grew by 70 percent (see Figure 1.3). The production of wool, a key commodity for the Argentine economy, underlay some of these changes: between 1850 and 1880 the ovine population rose from 7 million to 61 million, and wool exports from 7,681 to 92,112 metric tons. On the agricultural front, while in the early 1850s there was almost no cultivated land, almost six hundred thousand hectares were cultivated by 1872, and 2.5 million by 1888. Wheat, corn, linseed, barley, and oats were the main crops (Rock 1987, 133–38).

FIGURE 1.2 Main Destinations by Percentage of Total Spanish Emigration, 1888–1968

SOURCES: Sánchez Alonso 1995, 143; Vázquez-Presedo 1971, 39.

NOTE: These destinations represent over 90 percent of all Spanish Emigration during this period.

What explains the Argentine economy’s take-off and Argentina’s emergence as a destination for many European migrants? Essentially, the country benefited from a confluence of political and economic factors.6 An important factor was relative political unification after 1860 and the military conquest of territories formerly controlled by Amerindians (Rock 1987). Military expropriation of these lands made them available for agricultural exploitation. Increased efficiency and productivity, lower costs, and the advent of cheap, relatively fast trans...