![]()

1 Introduction

Migration raises high hopes and deep fears: hopes for the migrants themselves, for whom migration often embodies the promise of a better future. At the same time, migration can be a dangerous undertaking, and every year thousands die in attempts to cross borders. Family and friends are often left behind in uncertainty. If a migrant fails to find a job or is expelled, it can mean the loss of all family savings. However, if successful, migration can mean a stable source of family income, decent housing, the ability to cure an illness, resources to set up a business and the opportunity for children to study.

In receiving societies, migration is equally met with ambiguity. Settler societies, nascent empires and bustling economies have generally welcomed immigrants, as they fill labour shortages, boost population growth and stimulate businesses and trade. However, particularly in times of economic crisis and conflict, immigrants are often the first to be blamed for problems, and face discrimination, racism and sometimes violence. This particularly applies to migrants who look, behave or believe differently than majority populations.

Migration and the resulting ethnic and racial diversity are amongst the most emotive subjects in contemporary societies. While global migration rates have remained relatively stable over the past half a century, the political salience of migration has increased. For origin societies, the departure of people raise concern about a brain drain, but it also creates the hope that the money and knowledge migrants obtain abroad can foster development back home. For destination societies, the arrival of migrant groups can fundamentally change the social, cultural and political fabric of societies, particularly in the longer run.

This became apparent during the US presidential election of 2016. During the election campaign, Donald J. Trump promised voters that he would build a border wall to prevent Mexican immigration. Trump stoked up fear of Mexican immigrants by saying “They are bringing drugs. They are bringing crime. They are rapists”. At campaign rallies, Trump also tapped into anti-Islam sentiment, linking Muslim immigration to terrorism and expressing a desire for a Muslim registry. In January 2017 the Trump administration introduced a controversial ban on the entry of passport holders from seven predominantly Muslim countries. Although this policy met social and legal resistance, this reflected a campaign promise of a ‘Muslim ban’, based on reducing perceived security risks and curbing refugee migration to the US.

In Europe, the growing political salience of migration is reflected in the rise of anti-immigrant and anti-Islam parties and a subsequent move to the right of the entire political spectrum on migration and diversity issues (see Davis 2012). Parties like the Front National in France, the Lega Nord in Italy, and the Freedom Parties of Austria and the Netherlands have been established features of the political landscape for over two decades now. Although in most countries such parties have not been able to gain majorities, they are perceived as a major electoral threat by established parties, and their influence on debates is therefore larger than their voting share may suggest, as they tempt rival parties to adopt similar positions on immigration and diversity in order to retain voters.

In Europe, fears of mass migration came to a boiling point in 2015, when more than one million refugees and asylum seekers from Syria and elsewhere crossed the Mediterranean Sea. Concerns about immigration also played a central important role in the 2016 Brexit referendum, with 52 per cent of the voters supporting leaving the European Union (EU). In the lead-up to the vote, Nigel Farage’s United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) stoked up fears of mass immigration. Anti-immigration parties from across Europe have argued that free intra-EU mobility undermines national sovereignty, and that abolishing free movement – or leaving the EU – is the only way to regain control over what is portrayed as unfettered migration.

The increasing ethnic and cultural diversity of immigrant-receiving societies creates dilemmas for societies and governments in finding ways to respond to these changes. Young people of immigrant background are protesting against discrimination and exclusion from the societies in which they had grown up – and often been born – and claim their right to equal opportunities in obtaining jobs, education and practising their religion. Some politicians and elements of the media shift the blame to the migrants themselves, claiming that they fail to integrate by deliberately maintaining distinct cultures and religions, and that immigration has become a threat to security and social cohesion.

Migration is an inherently divisive political issue. There is little evidence that migrants take away jobs or that migration is the fundamental cause of deteriorating working conditions, welfare provisions and public services. In fact, most evidence suggests that migration has positive impacts on overall growth, innovation and the vitality of economies and societies. For the most part, the growth of diversity and transnationalism is seen as a beneficial process, because it can help overcome the violence and destructiveness that characterized the era of nationalism – this was for instance a major motive behind the creation of the EU.

On the other hand, the benefits of migration are not equally distributed across members of destination societies. Businesses and high-income groups tend to reap the primary benefits from the labour and services delivered by migrants. Lower income groups, who have often experienced a deterioration of working conditions, real wages and social security as a result of economic deregulation and globalization, enjoy few, if any, direct economic benefits from migration, while they are often most directly confronted with the social and cultural change that migration is bringing about. Some politicians are therefore tempted to rally support by blaming the most vulnerable members of society – migrant workers and asylum seekers – for problems not of their making.

Beyond the usual allegations that migrants take away jobs and benefits, and undercut wages, migration has been increasingly been linked to security concerns. On the one hand, this reflects genuine worries about the involvement of small fractions of immigrant and immigrant-origin populations in extremist violence and terrorism. International migration is sometimes directly or indirectly linked to conflict. Events such as 9/11 (the 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York and the Pentagon in Washington, DC) as well as the attacks by Islamist radicals in Europe and elsewhere involved immigrants or their offspring. This can lead to useful debates about how to counter such violence and how to prevent the marginalization and radicalization of immigrant populations.

It becomes more problematic when such attacks are used to stoke up xenophobia for political gain, by representing migration as a fundamental threat to the security, identity and cultural integrity of destination societies. This has led to the frequent portrayal of migrants and asylum seekers as criminals, rapists and terrorists, or as ‘foreign hordes’ plotting a takeover by bringing in foreign cultures and religions such as Islam. Anti-immigrant sentiment and migrant scapegoating by politicians and opinion makers have created a climate where far-right and racist attacks have flared up. It is in this political climate that extreme-right violence has proliferated, such as the attacks on New Zealand mosques in 2019, with a danger of provoking counterreactions by Islamist radicals. In this way, violence by white supremacists and Islamist radicals can feed into each other in a dangerous vicious circle.

This is by no means a uniquely Western phenomenon. As migration is globalizing, the cultural, social and economic changes that inevitably result from the arrival and settlement of large groups of migrants are deeply affecting societies around the world, often leading to polarization between social and economic groups opposing and favouring large-scale immigration. Oil economies in the Gulf region have the highest immigration rates in the world, and their economies have become structurally dependent on foreign labour. Lack of worker rights, prohibition of unions and fear of deportation leave migrant workers no choice other than to accept exploitative conditions. In Japan and Korea too, politicians often express fears of loss of ethnic homogeneity through immigration. The government of multiracial Malaysia has regularly blamed immigrants for crime and other social problems, and announced ‘crackdowns’ against irregular migrants whenever there are economic slowdowns. African countries have among the most restrictive immigration regimes in the world, and racist attacks and mass expulsions have regularly occurred in countries such as South Africa, Nigeria and Libya.

Migration is such a politically divisive issue because it is directly linked to issues of national identity and sovereignty. However, as migrants stay longer they become an increasingly permanent feature of societies, while economies have come to increasingly depend on continuous inflows of lower and higher migrant labour. Time and again, this has compelled governments to come to terms with such new realities by creating facilities for the legalization, integration and naturalization of migrants. As settlement takes place and migrants claim their place as new members of society, this is almost bound to create political tension and, sometimes, conflict.

Migration in an age of globalization

This book is about contemporary migrations and the way they are changing societies. The perspective is international: large-scale movements of people arise from processes of global integration. Migrations are not isolated phenomena: movements of commodities, capital and ideas almost always give rise to movements of people, and vice versa. Global cultural interchange, facilitated by improved transport and the proliferation of print and electronic media, can also increase migration aspirations by diffusing images and information about life and opportunities in other places. International migration therefore ranks as one of the most important factors in global change – both as a manifestation and a further cause of such change.

There are several reasons to expect the age of migration to endure: increasing levels of education and specialization combined with the growing complexity of labour markets will continue to generate demand for all sorts of lower- and higher-skilled migrant labour; inequalities in wealth and job opportunities will continue to motivate people to move in search of better living standards; while violent conflict and political oppression in some countries is likely to fuel future refugee movements.

Migration is not just – or even mainly – a reaction to difficult conditions at home: it is primarily driven by the search for better opportunities and preferred lifestyles elsewhere. Some migrants experience abuse or exploitation, but most benefit and are able to improve their long-term life perspectives through migrating. Conditions are sometimes tough for migrants but are often preferable to limited opportunities at home – otherwise migration would not continue.

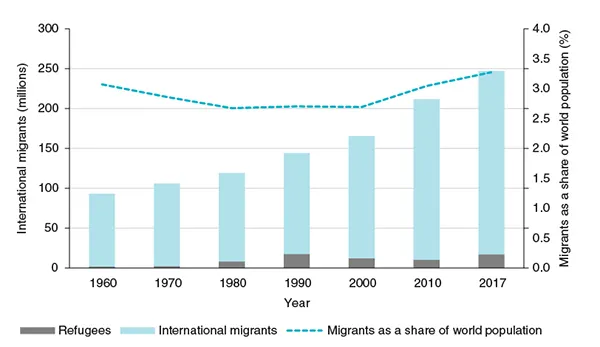

According to the Population Division of the United Nations, the global number of international migrants (defined as people living outside their native country for at least a year) has grown from about 93 million in 1960 to 170 million in 2000 and from there further to an estimated 258 million in 2017. Although this seems a staggering increase, in relative terms international migration has remained remarkably stable, fluctuating around levels of around 3 per cent of the world population (see Figure 1.1).

These facts challenge popular narratives of rapidly accelerating migration, as the number of international migrants has grown at a roughly equal pace with overall global population since 1960. Some researchers have argued that this percentage was actually higher in the late nineteenth century, during the heyday of trans-Atlantic migration between Europe and America. For instance, the approximately 48 million Europeans that left the continent between 1846 and 1924 represented about 12 per cent of the European population in 1900. In the same period, about 17 million people left the British Isles, equal to 41 per cent of Britain’s population in 1900 (Massey 1988: 381).

Although international migration has thus not increased in relative terms, falling costs of travel and infrastructure improvements have increased non-migratory forms of mobility such as tourism, business trips and commuting. Another important change has been increasing of long-distance migration between world-regions and the growing share of non-Europeans in global migrant populations. These trends have increased the diversity of immigrant populations in terms of ethnicity, culture, religion, language and education.

Figure 1.1 International migrants and refugees, as a percentage of world population, 1960–2017

Sources: Authors’ calculations based on the Global Bilateral Migration Database (World Bank) (1960–1980 data) and UNPD (2017) (1990–2017 data)

The vast majority of people remain in their countries of birth. Only 3 per cent of the world population are international migrants, so 97 per cent stay at home. Yet many more people move within countries. Internal migration (often in the form or rural–urban movement) is far higher than international migration, especially in large and populous countries like China, India, Indonesia, Brazil and Nigeria. It is impossible to know exact numbers of internal migrants, but they are likely to represent at least 80 per cent of all migrants in the world (UNDP 2009). The number of internal migrants in China alone has been estimated at levels of 250 million (Li and Wang 2015), which roughly equal the worldwide number of international migrants. Although this book focuses on international migration, internal and international mobility are closely interlinked and driven by the same development process...