The Revolution of 1944

Once the center of Mayan civilization, Guatemala had been reduced by centuries of Spanish rule to an impoverished outback when, at the turn of the 20th century, a coffee boom drew investors, marketers, and railroad builders to the tiny Caribbean nation. The descendants of Spanish colonizers planted coffee on large estates, fincas, worked by Indian laborers. Coffee linked Guatemala to a world market in which Latin American, African, and Indonesian producers competed to supply buyers in Europe and the United States with lowpriced beans. Success depended on the availability of low-paid or unpaid labor, and after 1900 Guatemala’s rulers structured society to secure finqueros a cheap supply of Indian workers. The Army enforced vagrancy laws, debt bondage, and other forms of involuntary servitude and became the guarantor of social peace. To maintain the uneasy truce between the Indian majority and the Spanish-speaking ladino shopkeepers, labor contractors, and landlords, soldiers garrisoned towns in the populous regions on the Pacific coast and along the rail line between Guatemala City and the Atlantic port of Puerto Barrios.8

When the coffee market collapsed in 1930, ladinos needed a strong leader to prevent restive, unemployed laborers from gaining an upper hand, and they chose a ruthless, efficient provincial governor, Jorge Ubico, to lead the country. Ubico suppressed dissent, legalized the killing of Indians by landlords, enlarged the Army, and organized a personal gestapo. Generals presided over provincial governments; officers staffed state farms, factories, and schools. The Guatemalan Army’s social structure resembled that of the finca. Eight hundred ladino officers lorded over five thousand Indian soldiers who slept on the ground, wore ragged uniforms, seldom received pay, and were whipped or shot for small infractions. Urban shopkeepers and rural landlords tolerated the regime out of fear of both Ubico and the Indian masses.9

Ubico regarded the ladino elite with contempt, reserving his admiration for American investors who found in Guatemala a congenial business climate. He welcomed W. R. Grace and Company, Pan American Airways, and other firms, making Guatemala the principal Central American destination for United States trade and capital. The Boston-based United Fruit Company became one of his closest allies. Its huge banana estates at Tiquisate and Bananera occupied hundreds of square miles and employed as many as 40,000 Guatemalans. These lands were a gift from Ubico, who allowed the company a free hand on its property. United Fruit responded by pouring investment into the country, buying controlling shares of the railroad, electric utility, and telegraph. It administered the nation’s only port and controlled passenger and freight lines. With interests in every significant enterprise, it earned its sobriquet, El Pulpo, the Octopus. Company executives could determine prices, taxes, and the treatment of workers without interference from the government. The United States Embassy approved and until the regime’s final years gave Ubico unstinting support. 10

As World War II drew to a close, dictators who ruled Central America through the Depression years fell on hard times, and authoritarian regimes in Venezuela, Cuba, and El Salvador yielded to popular pressure. Inspired by their neighbors’ success, Guatemalan university students and teachers resisted military drills they were required to perform by the Army. Unrest spread, and, in June 1944, the government was beset by petitions, public demonstrations, and strikes. When a soldier killed a young schoolteacher, a general strike paralyzed the country, and the aged, ailing dictator surrendered power to his generals. Teachers continued to agitate for elections, and in October younger officers led by Capt. Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán and Maj. Francisco Arana deposed the junta. The officers stepped aside to allow the election of a civilian president, a sacrifice that earned popular acclaim for both them and the Army. The Revolution of 1944 culminated in December with the election of a university professor, Juan José Arevalo, as President of Guatemala.11

Arévalo’s regime allowed substantially greater freedoms, but remained essentially conservative. Political parties proliferated, but most were controlled by the ruling coalition party, the Partido Acción Revolucionaria (PAR). Unions organized teachers, railroad workers, and the few factory workers, but national laws restricted the right to strike and to organize campesinos, farm laborers and tenants. The Army remained in control of much of the administration, the schools, and the national radio. Modest reforms satisfied Guatemalans, and the revolutionary regime was highly popular. Most expected one of the revolution’s military heroes, Arbenz or Arana, to succeed Arévalo in 1951.12

So sure was Arana of taking power that he laid plans to hasten the process. In July 1949, with the backing of conservative finqueros, he presented Arévalo an ultimatum demanding that he surrender power to the Army and fill out the remainder of his term as a civilian figure-head for a military regime. The President asked for time, and along with Arbenz and a few loyal officers tried to have Arana arrested on a remote finca. Caught alone crossing a bridge, Arana resisted and was killed in a gunfight. When news reached the capital, Aranista officers rebelled, but labor unions and loyal Army units defended the government and quashed the uprising. In a move they later regretted, Arbenz and Arévalo hid the truth about Arana’s death, claiming it was the work of unknown assassins. Arbenz had saved democracy a second time, and his election to the presidency was ensured, but rumors of his role in the killing led conservative Guatemalans, and eventually the CIA, to conclude that his rise to power marked the success of a conspiracy.13

After the July uprising, Arbenz and Arévalo purged the military of Aranista officers and placed it under loyal commanders who enjoyed, according to the US Embassy, “an unusual reputation for incorruptibility.” Unions enthusiastically supported Arbenz’s candidacy, expecting him to be more progressive than Arévalo. The candidate of the right, Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, lagged behind in the polls, and Arbenz would win in a landslide. Rightists made a final bid to usurp power in the days before the election. Along with a few followers, a purged Aranista lieutenant, Carlos Castillo Armas, mounted a quixotic attack on a military base in Guatemala City. He believed Army officers, inspired by the spectacle of his bravery, would overthrow the government and install him as president. Instead, they threw him in jail.14

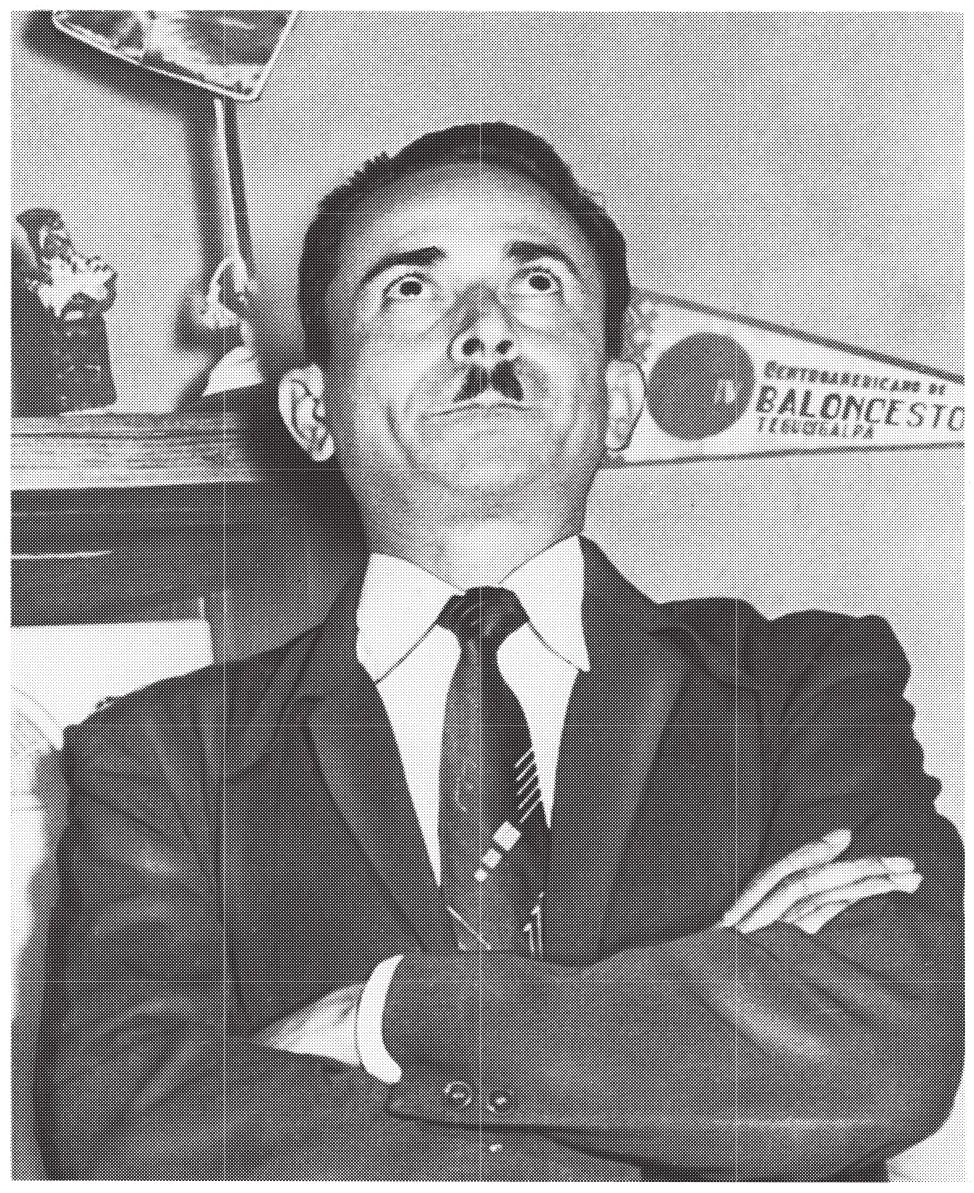

Castillo Armas came to the attention of the Agency [ ] in January of 1950, when he was planning his raid. A protégé of Arana’s, he had risen fast in the military, joining the general staff and becoming director of the military academy until early 1949, when he was assigned to command the remote garrison of Mazatenango. He was there when his patron was assassinated on 18 July, but he did not hear of the Aranista revolt until four days later when he received orders relieving him of his post. Arbenz had him arrested in August and held on a trumped-up charge until December. When a CIA agent interviewed him a month later, he was trying to obtain arms from Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza and Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo. The interviewer described him as “a quiet, soft-spoken officer who does not seem to be given to exaggeration.” He claimed to have the support of the Guardia Civil, the Quezaltenango garrison, and the commander of the capital’s largest fortress, Matamoros. He met with a CIA informer in August and again in November, just a few days before he and handful of adventurers mounted a futile assault on Matamoros. A year later, Castillo Armas bribed his way out of prison and fled to Honduras where he thrilled rightist exiles with stories of his rebellion and escape. He planned another uprising, telling supporters he had secret backers in the Army. This was delusion. After the July uprising, Arbenz was the Army’s undisputed leader, and he took steps to keep it that way.15

Carlos Castillo Armas in exile. Collection of the Library of Congress.

Partisan and union activity had grown amid the freedom of the Arévalo years, creating new political formations that later affected the Arbenz regime. The PAR remained the ruling party, but rival parties were tolerated. The federation of labor unions, the Confederación General de Trabajadores de Guatemala (CGTG), headed by Victor Manuel Gutierrez, claimed some 90,000 members. An infant union of campesinos led by Leonardo Castillo Flores, the Confederación Nacional Campesina de Guatemala (CNCG), began shortly after the July uprising to form chapters in the countryside. Toward the end of Arévalo’s term, Communist activity came into the open. Exiled Salvadoran Communists had opened a labor school, the Escuela Claridad, in 1947 and though harassed by Arévalo’s police, gathered a few influential converts, among them Gutiérrez and a onetime president of the PAR, José Manuel Fortuny. In 1948, Fortuny and a few sympathizers attempted to lead the PAR toward more radical positions, but a centrist majority defeated them. Shortly before Arbenz took office, they resigned from the PAR, announcing plans to form “a vanguard party, a party of the proletariat based on Marxism-Leninism.” They called it the Partido Guatemalteco del Trabajo (PGT).16