![]()

PART ONE

SOUFFLES 1–3 (1966)

IN CONFIDENT, PASSIONATE TONES, and brilliant, exuberant poetry and prose, the contributors to Souffles’ first three issues announce the beginning of a new phase of Moroccan literature and culture. Abdellatif Laâbi’s prologue to the first “manifesto-issue” describes its young writers as poised at a threshold. Wholeheartedly rejecting the cultural stagnation brought about by colonial acculturation and the subordination of Moroccan cultural production to the whims of imperial French tastes, these writers confront the social and political issues facing their newly independent country to produce a critically grounded Moroccan national culture. Laâbi envisioned Souffles as a nonpartisan venue for a new poetry and literature, open to a global authorship and intended for Moroccans and other decolonizing peoples around the world. In the second issue he reaffirms Souffles’ distance from Moroccan old-guard pseudo-literature—emblematized by Le petit Marocain (The Little Moroccan), an ultraconservative daily and holdover from the colonial period—and invites the reader to engage directly with intellectuals’ and artists’ works. Abdelkebir Khatibi’s essay on the Maghrebi novel echoes Laâbi’s observations and exhortations. Acknowledging the indispensable politicization of Moroccan, Algerian, and Tunisian literatures during these countries’ struggles for sovereignty, Khatibi questions the legitimacy of writing literature in French for a largely illiterate, non-French-speaking population, and demands a clearer relationship between aesthetic and political practices in the postcolonial context.

The essays in this section vividly demonstrate Souffles’ simultaneous rejection of the old submission to European frameworks and enthusiasm for new forms of decolonized culture. Abdallah Stouky’s scathing review essay on the 1966 World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, Senegal, protests the festival’s multiple objectifications of African culture and the use of venues such as museums and Italianate theaters that tend to divorce African cultural objects from their contexts. Stouky further reveals the downfall of Negritude: while for the preceding generation it was an aesthetic and political rallying cry, in 1966 it appears to him as an essentialist colonial anachronism that must give way to an independent African identity ready to face contemporary challenges. Ahmed Bouanani’s “An Introduction to Popular Moroccan Poetry” explores the traditions of indigenous Moroccan oral literature, detailing the history of its itinerant singers, sacred poets, and regionally diverse musical instruments, song forms, and poetic subgenres. Drawing attention to Moroccans’ centuries-old practice of orally transmitting history, Bouanani calls for a comprehensive study of these rapidly vanishing oral traditions.

Showcasing the range of contemporary experimental poetic production was the primary mission of these first three issues; the selections translated here highlight the stylistic diversity through which Souffles approached poetry as cultural critique. Laâbi’s “Doldrums,” invoking poisonous scorpions and scatological offenses, recasts his essayistic critiques of cultural stagnation in terms of human-embodied experience at its most chaotic. Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine’s “Bloods” overwhelms the reader with its turbulent stream of unpunctuated, uncapitalized prose and rejoices in blood’s long history of cultural significance as an ancient symbol of life and marker of identity, while simultaneously succumbing to a modern-day, paranoid view of blood as a biological vector for disease. The plural “bloods” of the title also testify to the literal and figurative pooling of the blood of those who disappeared during the years of lead, calling on this collective experience of loss to critique the boundaries that define family, community, tribal, and national allegiances. The speaker alternately rages with and against his realization that the coursing of blood and his attempts to contain it ultimately lead, through violence, to its corruption and loss. Although Khatibi’s tightly controlled verses recall the poetic innovations of Western modernism, they are most notable for the critical tact and subtlety that would become his trademarks. The “twilight dance of a dead leaf” in “Becoming” is reminiscent of Poundian imagism, while “The Street” and “Riot” pay homage to the street as a primary site of encounter with language and history, recasting the Baudelairean flâneur’s paradoxical solitude-within-a-crowd. However, these poems emphatically reconstitute these modernist commonplaces as vehicles for latent memories of the violence of colonization and decolonization.

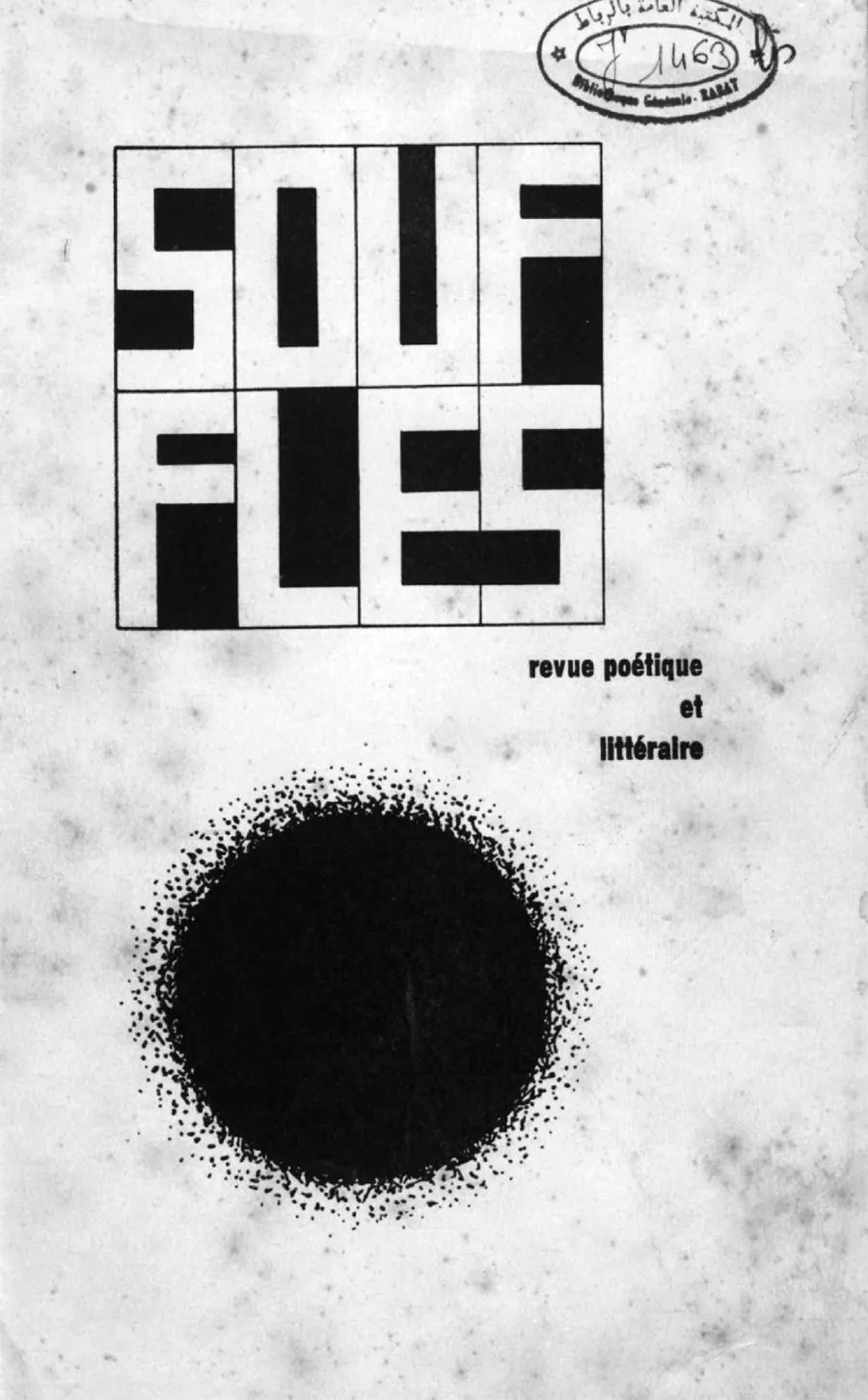

FIGURE 1. Front cover of the first issue of Souffles with painting by Mohamed Melehi and logo by Mohamed Chebaa. Souffles 1 (Rabat, 1966). Reprinted with permission.

![]()

SOUFFLES 1: FIRST TRIMESTER 1966

PROLOGUE

Abdellatif Laâbi

Translated from the French by Teresa Villa-Ignacio

The poets who have authored the texts of this, the manifesto issue of the journal Souffles, are unanimously aware that publishing in this venue means they are taking a stand at a moment when issues pertaining to our national culture have attained a degree of extreme tension.

The current state of literary affairs is not characterized, as some might believe, by a proliferation of creativity. The cultural disturbance that some individuals or groups are hoping will pass for a literary growth spurt is, in fact, only the expression of our ongoing stagnation or a certain number of misunderstandings about the deeper meaning of literary activity.

Petrified contemplation of the past, sclerosis of forms and themes, shameless imitation and forced borrowings, and the misplaced vanity of false talents constitute the adulterated daily bread with which the press, journals, and the greed of our rare publishing houses bludgeon us.

Even when we leave these multiple prostitutions out of the discussion, literature has become a form of aristocratism, a rosette on display, a force of intelligence and cunning.

This is not a quarrel between the ancients and the moderns. In fact, the literature ravaging the country today most often conceals a shocking eclecticism of heritages and borrowings from hearsay. It would even be possible for an objective critic to study outdated literary trends here where they are still in vogue. And since the tourist brochures speak of a “land of contrasts,” one will find in this literature whatever is needed to satisfy all curiosities, all nostalgias: the residue of classical medieval poetry, Oriental poetry of exile, Western romanticism, symbolism from the turn of the century, social realism, not to mention the results of existentialist indigestion.

As a result, “representatives” of “Moroccan literature” occupy a special place at international gatherings, and congresses of writers are held in our country. The reader is at once disoriented and nauseous. His dissatisfaction is all the more justified in that he can find some of his problems echoed in foreign literatures, those that various “missions” have benevolently placed at his doorstep. We can explain the oft-commented complex of our national literature by its current incapacity to “touch” the reader, to gain his attachment, or to provoke in him some kind of reflection, a wrenching away of his social or political conditioning.

On an entirely different level, Maghrebi literature in French, which at one time gave birth to so much hope, is currently stalled and seems, according to some observers, to belong to the domain of history. This literature must, however, be called into question today.

Two of its most brilliant representatives prematurely celebrated its demise with touching funeral ceremonies.1 Analyzing the situation of the colonized writer, his linguistic dramas, his lack of true readers, they concluded that this literature was “condemned to die young.”2

Others have abstained from falling into this pathetic determinism. But they are all ready, despite their lucid self-critique, to entertain the paradox of a suicidal literature that keeps going, in spite of everything, albeit in slow motion, along its path.

A glance through the most recent publications in French reveals that that those who have pronounced the imminent death of this literature have come to this conclusion too quickly. Although we should in no way ignore the issue of the very status of Maghrebi literature in French. This is a delicate issue, and we must approach it prudently while excluding all tendencies toward generalization. In fact, the situation of writers of the previous generation (Kateb Yacine, Mohammed Dib, Mouloud Feraoun, Mouloud Mammeri, Albert Memmi or even Driss Chraïbi), reveals itself to be closely tied to the colonial experience in its linguistic, cultural, and sociological implications. From the pacifist autobiographies of the 1950s to the protestatory and militant works from the period of the Algerian War, we may remark that despite the diversity of talents and creative power, this production was entirely inscribed within the framework of acculturation. It perfectly illustrates the relationship between the colonized and the colonizer within the cultural sphere. Thus, even when a Maghrebi was represented in these works or when autochthonous writers spoke up to denounce abuses, this literature almost always remained a one-way street. It was conceived for the public of the “Métropole” and destined for foreign consumption. That was the public it aimed to move to pity, in which it sought to awaken solidarity; that was the public to whom it needed to demonstrate that the fellah in Kabylia or the factory worker in Oran were not so different from the farmer in Brittany or the dockw...