![]()

Part I

CAREER DIRECTION

Choose a job you love, and you will never have to work a day in your life.

CONFUCIUS

Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do.

STEVE JOBS

There are three things extremely hard, Steel, a Diamond, and to know oneself.

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

YOUR STARTING POINT is to determine which field of work or which role to pursue, or at least to determine where to start. This fundamental direction setting is critical. It’s also difficult. Answers can be elusive.

To do this well, you’ll need to blend diverse styles of inquiry. Direction setting is a deeply personal endeavor. Intuitively seek insight and revelation. Look within yourself, identify your intrinsic strengths, sense where you might find passion, and learn from what happens to you. Imagine where your interests and values may lead. Direction setting also requires an external perspective. Conduct a structured and rational search. Investigate interesting fields, learn what people do there, and evaluate how you’d fit. And direction setting requires experimentation. Try out your ideas and then judge where to place your bets.

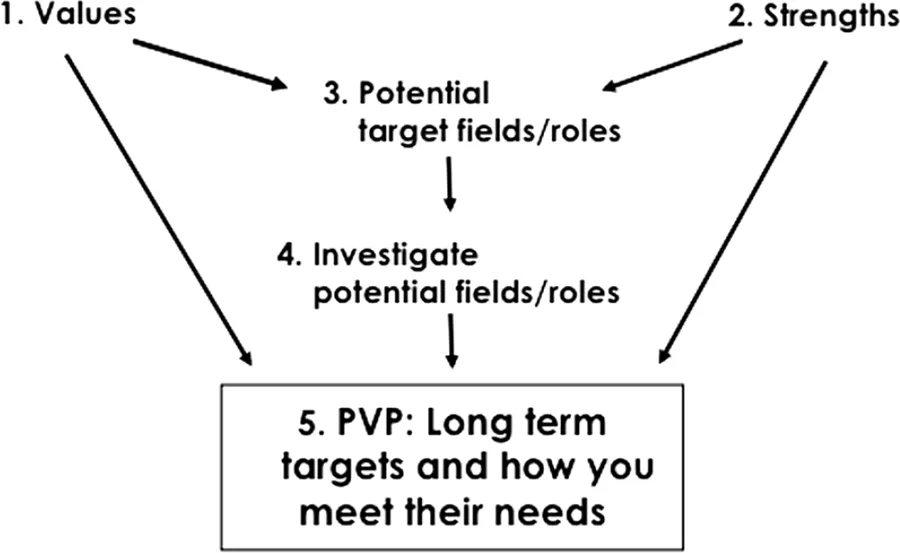

FIGURE PI-1 Part I: Develop Your Aspirational Personal Value Proposition

The five chapters of Part I present the progression of activities that incorporate these diverse ways of learning. Follow them to set your long-term career direction, as you see in Figure PI-1. I express that direction in terms of the aspirational personal value proposition (PVP)—your target field or role for the long term, what’s required to succeed there, and why you match those requirements.

Chapter 1 shows how to identify the fundamental values you derive from your work. Much like a founder setting a vision for the new company, you’ll begin your career strategy journey with values and aspirations.

Knowing your strengths is critical. You should seek to work in an area where you can use your strengths every day. You’ll enjoy it and accomplish a great deal. Chapter 2 demonstrates how to assess your strengths, parallel to the way strategists and marketers evaluate products before bringing them to market.

Potential fields and roles come next. How to imagine fields and roles that reflect your fundamental values and strengths is presented in Chapter 3.

On the other side of the ledger are the characteristics of different fields and roles and what’s required to thrive in them. Chapter 4 shows how to investigate them, following study processes like the ones business strategists use to assess industries and companies.

Everything comes together when you set your aspirational PVP for the long term, a concept like the value propositions that executives hope to deliver when kicking off new product development. That’s the subject of Chapter 5.

Moving through these five steps is a proven process. Everyone I’ve known who developed career strategy in this way uncovered valuable insights. Most set aspirations and plans for their futures.

![]()

Chapter 1

FUNDAMENTAL VALUES LEADING TO A CALLING

A BUSINESS FOUNDER STARTS with his or her interests, ideas, and skills and determines how to meet the needs of the market. The founder designs products to fit the market and establishes the capabilities to manufacture and sell them. In established companies, fundamental aspirations guide decisions big and small. When contemplating a big strategy shift, corporate leaders test that shift against those aspirations. If the shift doesn’t fit, that raises questions about whether it’s a good idea.

Just as they do in business, uplifting aspirations can guide your work life. They motivate: the word aspiration suggests hope and opportunity. They lead to action: aspirations you believe in will target personal growth, stimulate initiatives to position yourself to be competitive, and guide your search for opportunities. Before your strategy can take you to your desired destination, you need to know where you wish to go.

Determining what you want from work, however, can be a tall order. Work is a financial necessity for almost everyone, and that work sometimes will require sacrifice. Work can be drudgery, but it also can be fun and exciting. The competition can be energizing. There’s no perfect scorecard to consult for answers. Digging into aspirations is a big part of career strategizing.

My goal in this chapter is to show you how to structure thinking about your own values related to work. I’ll begin by describing the job/career/calling framework. I’ll take a deep dive into the factors that underpin this framework and then describe how to use it to guide your own thinking.

Jobs, Careers, and Callings

What matters most to you at work? Most people must wrestle with this question to get to bedrock values. This inside-out thinking is highly personal, but you don’t have to do it without guidance. The experiences of others offer lessons into which aspirations provide the greatest prospect of happiness and satisfaction.

The best framework I’ve seen of attitudes toward work is the job/career/calling model, introduced to me by Amy Wrzesniewski from Yale:1

• Job—People focus “on the material benefits of work to the relative exclusion of other kinds of meaning and fulfillment.” They may contain time at work, spend some work time thinking about what they’ll do after work, and resent occasions when work requirements expand.

• Career—“The increased pay, prestige, and status that come with promotion and advancement are the dominant focus of their work.”

• Calling—People “work not for financial rewards or for advancement, but for the fulfillment that doing the work brings. . . . The work is an end in itself, and is usually associated with the belief that the work contributes to the greater good and makes the world a better place.”

Investigating people from different walks of life, Wrzesniewski found that roughly a third fall into each category. (Throughout the book, I use the words job and career in a conventional way. In this part of Chapter 1, however, I use those words in the particular way defined in the preceding list.)

When I first saw this model, I smiled to myself and nodded. The job/career/calling model captured much of what I’d experienced in my own work life and what I’d observed in others. I knew that if I could use this idea to help people find callings or at least begin their journeys, I’d have something big.

When I began the research that led to this book, therefore, a principal goal was to classify people among these categories and learn what causes them to end up in one category or another. I did that by talking to executives, managers, and professionals, most in their thirties and forties. As I deployed this emerging thinking into the classroom, I added MBA students to the mix, most of whom were in their late twenties and early thirties. I asked about motivations and values, along with accomplishments and how they felt about their work lives. I’ll describe what I’ve learned about these differences in a moment, but first let’s get some misconceptions about callings out of the way.

Some people hear the word calling and assume that a calling requires a great deal of self-sacrifice and denial. They imagine people working with charities or religious institutions—an extreme version being Mother Theresa in Calcutta’s slums. They imagine people in lower-paid positions than they otherwise could have. I’m sure some calling people are like that, but that level of sacrifice and denial isn’t what I’ve found. Some highly paid corporate leaders have callings; others don’t. Some Legal Aid attorneys have callings; others are there because it was the only position they found. Some people in public service roles bring career or job mentalities to their work. Some physicians are healers; others are in it for the money. None of the calling people I’ve known live in conditions anywhere close to those of Mother Teresa’s life. Although they work hard, most of these people find their lives appealing—with average to above-average incomes and not much difference in hours at work.

Many assume that once you find a calling, it’s with you for the rest of your life. In the stories in this book, you’ll see some people who, so far at least, are pursuing the calling they first found. But you’ll also see others who find callings, lose them, and then move on to something else.

People may suppose that only the young without family obligations can sacrifice in the way required to pursue a calling, especially a calling that comes with a modest paycheck. Callings, however, are far more prevalent among experienced people. Few young adults really know what they want from work. They’re experimenting with possibilities, largely bringing a career mentality to decisions about which field of work to pursue and which positions to accept.

Some assume that callings arrive in a visionary way, perhaps coming down from on high, and feel like a command. I’m sure that’s possible, and it certainly would clarify things. However, only one person I’ve worked with on careers had anything close to that experience. Callings, at least in the way I’ll be using the term in this book, are far more likely to result from a multiyear journey that includes some trials and some errors than from a single astonishing flash of insight.

At first glance then, calling people don’t look much different than everyone else. They have good-looking resumes, but so do many others. Their occupations largely overlap the occupations of career or job people. Their academic preparation is similar. On paper, it’s hard to see who’s who. So what causes the differences among people with jobs, careers, and callings?

. . .

One result of this classification exercise is no surprise. Just as what business strategists find when they analyze market segmentation, some people fit squarely at the center of one of the categories, and others sit at the borders between categories. That said, the patterns are clear.

Although people with callings are different, it’s not their occupation, work hours, level of sacrifice, or field of work that distinguishes them. Calling people are different because they see their work as a positive end in itself. They emphasize service to others, achieving excellence at their craft, and/or strengthening their institution. They accept and may like the things they take out of work, such as pay and prestige, but they don’t emphasize them. They’re ambitious and accept sacrifice to meet goals in the work. They enjoy work most of the time and take personal satisfaction from it. Although they encounter disappointments, those frustrating moments seldom take center stage. More than a third of the people I’ve spoken with have callings or are close.

The majority of people in my research take career mentalities to work. For career people, advancement, pay, prestige, and power are front of mind. These careerists are ambitious and will sacrifice to succeed. They have widely different levels of happiness and satisfaction. Some see themselves as winning; they’re happy and optimistic. Others are uneasy and insecure. They worry that they’re not advancing at the right pace or that they’re not in the role they merit. They wonder whether they might find something better. If this feeling continues for some time, they may find that their work has dropped into the next category—jobs.

Only a few of the people I’ve known see their work as jobs. Job people find little meaning in what they do. They hope to contain sacrifice while earning acceptable pay. Much of their energy goes to activities outside work. Many are looking for something new. (I assume that the small proportion of job people I’ve encountered relative to Wrzesniewski’s research reflects my focus on managers, professionals, and students whom I met because they were committed to developing personal strategies, rather than on a more general population.)

I’ll explore all this in depth in the rest of this chapter. I’ll begin with values in the work itself (service, craftsmanship, institution, and ambition), then review what’s taken from work (money, prestige, and power), and finish with the conditions of work (organization culture and sacrifice). You’ll see how calling people view these values and how career and job people diverge.

The Work Itself

People with callings put a high priority on the work itself. They are ambitious and hope for big accomplishments in one, two, or all three of these areas: serving others, attaining excellence in the work, and strengthening their institution and the people there.

Service

Many people with callings emphasize serving others. That service can be hands-on. They also can serve through their role at an institution. Those institutions can be direct service providers, such as charities or public service organizations. They can be businesses or professional firms whose better products or lower prices improve customers’ lives.

Career and job people are different. When making career choices, few put service high on the list. Career people may put energy into their work at service-driven institutions, but for them it’s mostly with the expectation that their contributions will be rewarded. I’m not suggesting that they don’t care about other people, but in their work, other things come first. Job people do what’s required to meet standards and little else. If that includes service, fine; but they don’t seek service.

Craftsmanship

When I use the term craftsman, I mean someone who strives toward excellence at what he or she does, who believes that quality is intrinsically worthwhile, and who seeks opportunities to improve whether or not that excellence comes with rewards. Craftsmen want to be world class in their fields. This kind of excellence can motivate university professors who hope to reshape thinking in their fields. It can motivate factory managers striving to achieve zero defects. Craftsmen can be found doing most anything—from the operating room to the court room to a cubicle without windows several floors below the corner office.

Craftsmanship is the leading motivation for some calling people, and most calling people pay attention to it because it can help them meet other high-priority goals.

Career people also can value craft, because skills can lead to advancement. But their priority is advancement, not excellence. Few job people take satisfaction from their craft and seldom select a position with that in mind.

Institution and Colleagues

Most calling pe...