![]()

1

HOW I DIVORCED MY ROBOT WIFE

Visionary Futures between Science and Literature

ON JUNE 12, 1957, the article “How Will Humanity Live in the Next Century?” in the People’s Daily announced: “The future begins today! Having gone through the age of stone, bronze, and iron, humanity has now entered the age of plastic.” The article reported on forecasts by Soviet scientists reflecting the hopeful anticipation on the eve of the Sputnik launch: synthetic fibers and artificial leather would solve all clothing problems; abundant crops would feed an exponentially growing population; cancer would be defeated and people would live longer; climate would be modified at will; flowers would bloom in the desert.1 Similar predictions were echoed in a variety of publications in the following two years, and although no longer prominent by the early 1960s, they resumed around 1978. How were people to prepare themselves for and contribute to the momentous changes that appeared so imminent in the late 1950s and late 1970s alike? What sorts of labor and knowledge would bring them about? What cultural forms would foster the moral and physical qualities leading to their realization? Forgotten materials depicting the technological futures of humanity, including popular science magazines, children’s stories, science fiction, and drama offer some answers. These diverse genres mediated ideas of useful labor and valuable knowledge at times in which imminent technological change was at the center of political and cultural discourse. The hopes they convey instruct us on the ways in which socialist China partook in an anticipatory imaginary of technological modernization shared across the globe.

Chinese revolutionary novels and movies, in fact, rarely provided full-fledged representations of future communist life. Rather, they mostly hinted at the future as a horizon lying outside the representational frame—the future was the off-screen object of the socialist realist gaze.2 Science-related narratives, by contrast, presented audiences with detailed descriptions of the material world that lay ahead. Unlike most revolutionary narratives, they depicted enjoyment instead of celebrating sacrifice. And while what is represented is likely to appear less attractive than what is merely suggested, these visions may have nourished people’s fantasies and helped create objects of desire not solely through the representation of models of behavior but also through the presentation of worlds characterized by abundance and well-being.

This chapter begins with a drama written and mostly set in 1958, the last section of which projects the protagonists into 1978, and then looks at how a children’s story published in 1978 returns to the aspirations of the 1950s. These first two sections explore an unresolved tension between the exaltation of manual labor and the anticipatory imagination of a laborless world within socialist science-related genres; the last part of the chapter shows how science fiction stories published during the late 1970s and early 1980s dismiss manual labor altogether. The change in post-Mao narratives is not so much in the imagination of the world that people would inhabit in the future as in the kind of labor deemed necessary to achieve it. Post-Mao science fiction associates manual labor with primitive stages of evolution, defective female robots, and uncouth ways of life. The laboring body is no longer the essential element that defines humanity but rather an obstacle to future developments—the subhuman residue of a technological regime about to be overcome.

Laboring Bodies, Writing Pain

Shisan ling shuiku changxiangqu (Rhapsody of the Ming Tombs Reservoir), a drama written by Tian Han in 1958 and adapted into a film the same year, reflects the massive mobilization of labor that characterized the Great Leap Forward. The drama is an extraordinary paean to the power of manual labor to transform nature and to the joy that this entailed. Excavation work for the Ming Tombs Reservoir began in February 1958 and was completed in late June. About 400,000 people were involved in this endeavor, duly advertised and portrayed through poems, songs, paintings, photographs, and postage stamps. Tian Han was one of the many prominent intellectuals and writers who traveled to the site. He visited in June 1958 on his way back to Beijing from a temple in the Western Hills, where he had been writing his better known drama Guan Hanqing, and immediately was inspired to celebrate that “magnificent undertaking” through his writing. Initially hesitating over whether he should compose a poem or a play, he was urged to write a play by Jin Shan, who at the time was the vice-director of the China Youth Art Theater.3

The writing of the drama itself proceeded at Great Leap Forward pace, inviting parallels between the labor depicted in the play and the fatigue that the playwright must have experienced in composing it in record time. It was apparently Jin Shan’s suggestion that they revert to the working rhythms of the “national salvation theater” in wartime Shanghai, consisting of “writing one page, rehearsing one page” (xie yi ye, pai yi ye); that is to say, rehearsing while the play was still being written. Every evening a troupe member would go to Tian Han’s home to collect his draft. The image of an actor standing outside Tian Han’s home, waiting in the twilight for yet another page to be delivered, might better convey the pressure of socialist mobilization than any top-down vision of the propaganda state. Writing at such moments of political mobilization required a huge effort on the part of writers and other cultural producers, an effort involving bodily discipline no less than psychological compliance, ensured through peer pressure as well as strict management of time. Later studies report that Tian did not sleep for several days and completed the 13-scene play in a week. The China Youth Art Troupe brought it to the stage with equal speed under the direction of Jin Shan himself. The Rhapsody of the Ming Tombs Reservoir was immediately performed in factories and rural communes. Ouyang Yuqian hailed it as a “magnificent epic, a lyric poem brimming with socialist enthusiasm. In the drama, both the playwright and the director have broken old rules and created a new form using new techniques.”4

Rhapsody of the Ming Tombs Reservoir vividly illustrates the futuristic rhetoric of the Great Leap Forward. It depicts the reservoir as a microcosm of society, a site where nothing less than the totality of human relations is redefined through collective labor. The script is concerned not only with assessing the correct handling of the relationship between technical expertise (zhuan) and political conscience (hong), on one hand, and manual and intellectual laborers, on the other, but also with the problem of how to write such a play. The dialogic form of the drama proves to be an effective medium both to redefine these relations and to explicate its own poetics, which I will call a “poetics of practice.” In the opening scene, a wide range of characters representing various professional and social groups—including a specialist of hydraulics of the Yuan period, a historian, a biologist, and a writer—discuss the plans for the reservoir and the benefits it will bring. The reservoir, it is said, will be much larger than the Kunming Lake (in the Summer Palace in Beijing); it will put an end to floods, supply drinking water, and provide a beautiful tourist destination. A discussion between the biologist and the political commissar brings the main point home: when the specialist argues that heavy rains will come before they can complete the work and will destroy everything, the political commissar replies that once the masses are unleashed nothing will be impossible. The whole play is an illustration of this claim.

The play emphasizes that labor itself unites people from all walks of life and from all parts of the world in a war against nature; thus, Rhapsody traces a process of unification. The dramatic form allows for doubts and reservations to be expressed and then corrected by a more committed interlocutor—by either the political commissar or a model laborer or both. In the eighth scene, the “writer” Hu Jintang (the quotation marks in the list of characters signal that he will turn out to be a villain) interviews a labor hero and learns about how he had jumped on a driverless locomotive, dashing forward at full speed, to pull the brake and reduce the damage in the crash. The young man was completely unconcerned about getting hurt: what mattered most to him was saving the freight cars. Thanks to the training he had received from the party, he knew how to act in such emergencies. At this point, Hu Jintang asks a political commissar whether the hero’s testimonial might be a little “formulaic” and is rebuked for having “no understanding of the new socialist ethics.”5 The script proceeds from this series of unsuccessful utterances and incorrect assumptions through the unmasking of enemies of the people to the reinforcement of group cohesion, culminating in a euphoric scene of song and dance. Thus, the transformation of polyphony into monophony—the unification of thought in the name of shared human nature based on the altruistic passion for labor—is dramatized.

The various scenes in which artists and writers attempt to portray what they are witnessing suggest that the play is in part a document on how to write about the building of the reservoir—or about any form of labor. As it turns out, merely participating as bystanders or even interviewing the laborers will not do. There is no way to write about such an enterprise without participating in it personally. The problem of mind versus hand becomes irrelevant when the premise is that to describe or understand something, one needs to first do it. Even Mr. Jackson, an English journalist who had incorrectly assumed that the project involved forced labor, ends up embracing this poetics of practice: “I have to clarify that I am not here in the function of a foreign observer but to participate in work, because if I didn’t, I wouldn’t be able to write a good report.”6

Documenting a high point of socialist mobilization, Rhapsody celebrates manual labor as the force that propels history forward. In the film version, which is often mentioned as China’s first “science fantasy film” (kehuanpian), dialogue plays a much lesser role. The film mostly focuses on the euphoria generated by frenzied collective labor. Key to its representation is the variation in rhythm in the actors’ movements, music, and camera work. How laboring feels depends on the laborers’ social position and on their relation with the means of production; but when the labor performed is essentially the same as that performed under the oppressive regimes of the past, how can this difference be represented visually? The film begins with a panning shot of the hilly landscape of Changping district in 1291. The voiceover introduces the Mongol ruler Kublai Khan and the hydraulic engineer Guo Shoujing, thus linking the building of the reservoir to the Mongol ruler’s efforts to extend the Grand Canal more than six hundred years earlier. A high angle shot shows corvée laborers grudgingly shoveling under the whip of mounted guards at the time of the Yuan dynasty. The scene extends deep into the distance with the laborers almost merging into the earth-filled landscape. The humming soundtrack and the plaintive voiceover emphasize how slavelike labor in the old society was painful and life-threatening. The contrast with socialist labor could not be starker. Low-angle tracking shots show the workers at the reservoir vigorously moving in unison, with different groups responding to one another in cheerful work songs, at times initiated by a female soloist. Collective labor is the source of happiness; it is healing, life-giving, the very basis of human community, to the point that the party representative intervenes to rein in the excessive exuberance of the workers to prevent them from harming themselves.

Hard labor also makes up for technological backwardness. Footage of Mao Zedong visiting the construction site is inserted in the film, and he promises that more tools and machines will be delivered to the workers. The script emphasizes, however, that tools and machines are less important than the human beings who handle them. Toward the end of the film, an intertitle announces a change of setting to “twenty years later,” 1978.7 The film culminates in a futuristic vision of a leisurely utopia in which production is automated and digital gadgets connect people with faraway relatives. A young woman passes around a sort of tablet computer, showing a video-letter she has received from her parents. Rain is stopped with a phone call. A jet spaceship crosses the sky. Life in the Ming Tombs People’s Commune in 1978 is bountiful and its inhabitants show off synthetic clothes with “national characteristics.” What apparently most struck audiences was this description of the world twenty years ahead. Many expressed their wish to know more, and in response a leaflet was issued, “Shisan ling shuiku changxiangqu zhengqiu dajia lai changxiang: 20nian yihou woguo de mianmao” (Rhapsody of the Ming Tombs Reservoir asks everybody to imagine: Our country twenty years from now), inviting everyone to join in the imagination of what the future would bring.8

Although most of Rhapsody of the Ming Tombs Reservoir illustrates the moral qualities and labor required to build socialism, the last act transports viewers into a perfect world in which hardship has been overcome. The drama thus illustrates two different notions of the future: the first understood as a sense of anticipation—the expectations that shape everyday life as it unfolds; the second is a point of higher perfection—a segment of time that is largely different from the present. Both notions are operative in Chinese socialist realism. How to represent them constituted its core problem, and Tian Han’s Rhapsody is a rare case in which both are visualized. The question of how life would be twenty years ahead will be picked up again by the science fiction writer Ye Yonglie, some twenty years later.

Little Smarty, Synthetic Futures

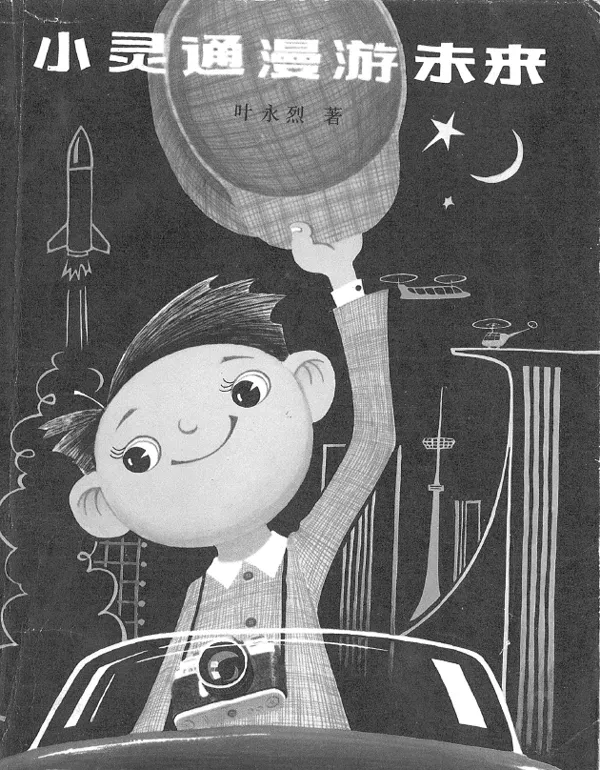

In 1977, the science fiction writer Ye Yonglie was asked by editors at Shanghai Children’s Literature Publishing House to give a lecture on the theme “looking forward to the year 2000.” The writer dug out a manuscript he had first drafted on the basis of science news snippets while he was in college in 1961. He updated it for his lecture and had it published as Little Smarty Travels to the Future a year later.9 As the first science fiction book for children published after the Cultural Revolution, Little Smarty reportedly had an enormous impact. After a first run of 1.5 million copies as an illustrated book, it was reprinted as a serial picture booklet (lianhuanhua) in three different editions, reaching a total of 3 million copies, a record among Chinese science fantasies. “Just as nowadays almost every child knows Superman and [the Japanese cartoon] Ultraman,” writes Yin Chuanhong, an editor at Science and Technology Daily who was ten years old when Little Smarty made his first appearance, so at that time “nearly every child knew Little Smarty—the savvy, curious, and knowledgeable young reporter with a round head and big ears.”10 Little Smarty is featured on the covers of the various editions against a background of futuristic landscapes that only underwent slight changes over the years, either waving his hat or pensively holding an open book, while behind him a flying car is about to take off and a hanging train gives the impression that passengers were to ride in it upside down (see Figures 1 and 2).

FIGURE 1. Front cover of Xiao Lingtong manyou weilai (Little Smarty travels to the future) (Shanghai: Shaonian ertong chubanshe, 1978).

FIGURE 2. Front cover of serial picture book (lianhuanhua) version of Xiao Lingtong manyou weilai (Little Smarty travels to the future) (Shenyang: Liaoning meishu chubanshe, 1980).

Lit...