![]()

Part One

O Nordeste in the Cold War

![]()

1

Revolution in Brazil

Historical Context and Key Players

It is a race: The hope of progress against spreading despair. And time is rapidly running out.

—CBS news anchor Eric Sevareid describing the potential of new development projects in Northeastern Brazil, The Rude Awakening, 1961.

IN THE YEARS surrounding the Cuban Revolution and John F. Kennedy’s Latin American aid program Alliance for Progress, revolution or evolution (modernization) were often depicted as the two possible paths for the Third World. As suggested in the above quote from a CBS news report in 1961, the debate about revolution or evolution suggested a feeling of urgent and imminent change. While this sentiment is at odds with the trope of o Nordeste that defines the region as impervious to change, drastic changes were occurring in the region in the 1950s and 1960s. During this period, Conservatives and rural social movements portrayed one another as the enemy, but they all advocated for some form of agrarian reform as a solution to regional poverty. The widely held belief in the need for change in the landholding system demonstrates that the traditional rural elite had lost their hegemonic power, allowing for an opening in the political landscape. Northeastern large landowners could no longer control the terms of political debate as they had in the past; they were forced to enter into a battle among numerous groups and individuals all seeking to gain popular support for their political projects and visions of change for the region. Scholar Fernando Antônio Azevedo has labeled this transformation as the ending of “agrarian peace,” or the end to the domination of the rural elites who had ruled with the privileges of the old rural oligarchies, maintaining “peace” by overexploiting rural labor and excluding rural workers politically and socially.1

This chapter introduces the major political and cultural actors who held stakes in projects advocating for change in Northeastern Brazil and provides background information about the 1950s and 1960s to contextualize the debates analyzed in the chapters that follow. Although most of the book focuses on the period from 1959 to 1964, it is necessary to understand what led up to the dramatic political debates, protests, land seizures, labor strikes, and revolutionary cultural and educational projects that characterized the era. This chapter also describes some of the key events and actors in the late 1950s and early 1960s; it is organized into stories about the movements or political parties instead of an all-encompassing chronological narrative. Analyzing the different “origin” narratives or how, why, and when the different groups began to take interest in the rural Northeast also shows how such stories relate to the trope of o Nordeste.

Origins of the Ligas Camponesas

Although disparate origin stories offer a wealth of reasons why the rural social movement that came to be known as the Ligas Camponesas began in the mid-1950s, the most commonly repeated version starts with death. In 1954, around 140 rural workers formed the Sociedade Agrícola e Pecuária dos Plantadores de Pernambuco (SAPPP, the Agricultural and Livestock Society of Pernambucan Planters) on the former sugar plantation named the Engenho Galiléia, “Galilee Planation.” According to most accounts, resident rural workers had been borrowing the communal coffin, or loló, from the local municipal government when a community member died. After the body was buried, the coffin had to be returned to the municipal depository. The mutual-aid society began as a way to guarantee workers the right to have their own coffins when they died, a fate that came early to most rural Northeasterners in the 1950s.2 Even though the rural workers elected the owner of the Engenho Galiléia as their first honorary president, his initial support for the association quickly waned. By early 1955, landowner Oscar de Arruda Beltrão demanded the shutdown of the association, and he moved to expel rural workers and tenant farmers from his lands. The rural workers resisted their expulsion by seeking assistance from Recife lawyer Francisco Julião, who was rumored to defend rural people’s rights. Julião began organizing a legal case for the expropriation of the Engenho Galiléia. As the case evolved, journalists renamed the SAPPP the Ligas Camponesas, drawing a connection between the mutual-aid society and the defunct Communist Party Peasant Leagues (1946–48). At the end of 1959, the Galileus (workers residing on the Engenho Galiléia) won the legal case for the expropriation of the Engenho Galiléia, and the Ligas Camponesas started to expand rapidly throughout rural communities in the Northeast.

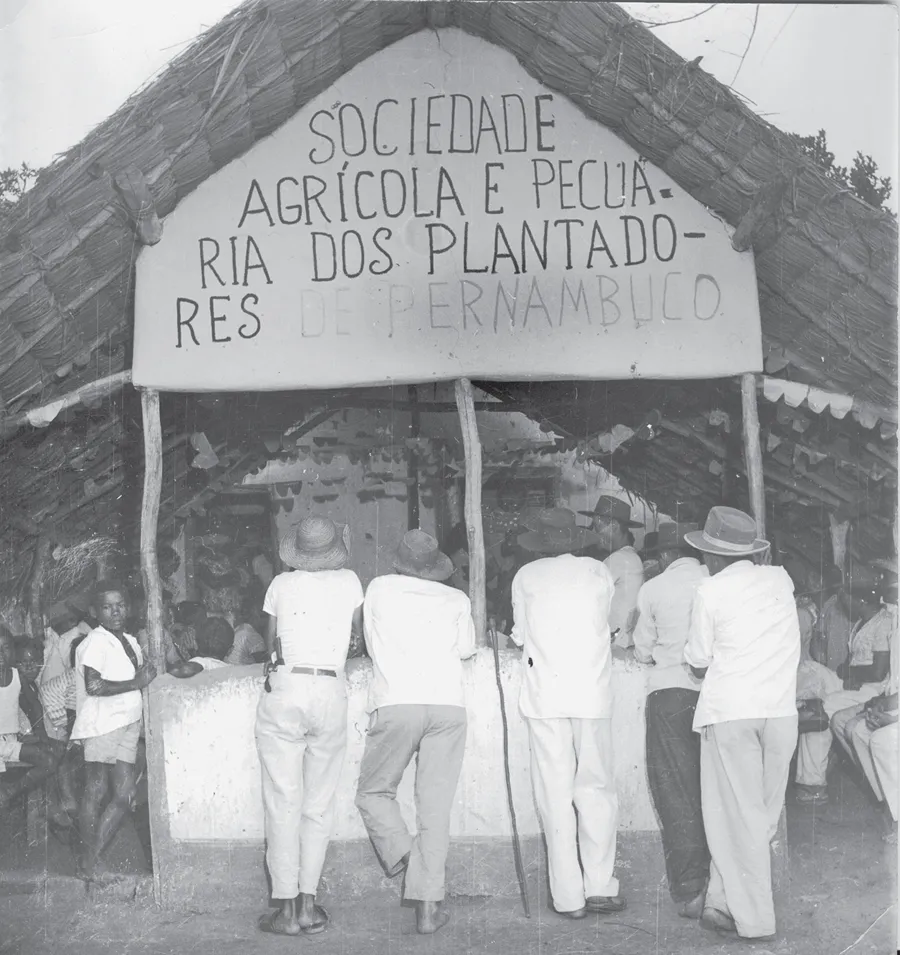

Although the funerary story is widely accepted, it has also been nordestinizado, that is, turned into a story that reaffirms commonly held beliefs about o Nordeste and nordestinos.3 Stories about the frequency of deaths linked to impoverishment and the ceremonies surrounding death in the Northeast flourish in popular culture and scholarship, forming a key strand in the trope of o Nordeste.4 This version of the origin story emphasizes the harshness of regional poverty, portrays the rural workers as fatalistic and nonpolitical victims who lack the material conditions to afford coffins, and suggests that the social movement developed because of leader Francisco Julião. An article entitled, “Now, They Have a Coffin,” which was accompanied by the photograph in Figure 1.1, provides a clear example of how the mainstream Brazilian media drew from the trope of o Nordeste in their coverage of the Ligas Camponesas.5 The article begins by describing the author’s perception of the “misery” he finds upon arriving at the Engenho Galiléia:

Without any previous understanding, if one arrived in front of this shed covered in palm fronds, a simple hut with a rustic sign, they would not believe it is the site of the most famous nordestina Peasant League. . . . The land, completely eroded, almost doesn’t grow anything other than manioc. Dirty children with extended bellies emerge from the miserable huts alongside men with fixed stares and women who are prematurely aged.6

The opening paragraph draws from the trope of o Nordeste in its description of poverty. The article emphasized the funerary version of the Ligas’s origins in the title, the final sentence, and Zezé de Galiléia’s highlighted response to a question about the benefits of the Ligas, in which he says the Ligas provided individual coffins for community members. But a deeper reading of Zezé’s complete response to this question suggests an alternative explanation for the popularity of this story.

FIGURE 1.1 The photograph of the SAPPP building and rural workers appeared in O Estado de São Paulo in 1961, although the building was probably constructed between 1954 and 1959 before the SAPPP became known the Ligas Camponesas.

Source: “Agora eles têm um caixão, . . .” O Estado de São Paulo, August 8, 1961, 7. Courtesy of O Estado de São Paulo.

Although the article focuses on how the Galileus started the association to provide coffins to community members, Ligas leader Zezé (José Francisco de Sousa) seems to be telling the story to prove that neither Francisco Julião nor the Galileus were communists. He counters the idea that the community members are brainwashed victims by discussing a political issue about literacy requirements for voting enfranchisement. As Zezé said:

The Ligas are defending our rights and are helping us. Look, before, when one of us died, the coffin was borrowed from town hall. After the body was lowered into the pauper’s grave, the coffin was returned to the municipal depository. Today, the Liga pays for the funeral and the coffin goes into the ground with the body. They go around saying that Dr. Julião is a communist. But a communist wouldn’t do that. Here, we are all Catholics. Dr. Julião is our friend. We don’t vote for him because we don’t know how to write.7

In his response, Zezé offered an alternative version about why the community formed the SAPPP. His version portrayed community members as consciously forming the association as a form of protection and resistance.

We established this association [SAPPP] to fight against our expulsion from the land. The Engenho’s owner lived in Recife and charged us all foro (payment for land one cultivates) without ever being interested in what was happening here. The land almost produced nothing, but we went on surviving. All of a sudden, the landowner decided to increase the foro. But we couldn’t pay more. We refused. Since the police wouldn’t solve the case, the plantation owner went to the Justice department. We had to defend ourselves and for this reason, we started the association.8

Although the rural workers on the Engenho Galiléia may have included the need for individual coffins on their list of reasons for staring a mutual-aid association, as this example demonstrates, community members probably had additional or other reasons for forming an association. According to other accounts, the community organized the SAPPP to build a school on the Engenho and hire a state teacher.9 A former Ligas participant remembered forming the SAPPP to pay for a community dentist and to assist pregnant women, young mothers, and infants.10 Beyond the community’s service needs, another version describes the political motivations behind the formation of the mutual-aid association, linking leaders of the SAPPP to an earlier Communist Party rural social movement from the 1940s.11

Although scholars have argued about which version is true, I am not sure it is possible to determine absolute truth in this case. Not only are multiple truths likely, but many of the stories also carry reflections of the time period and politicization of agrarian reform. Although Zezé’s explanation related to rising costs of the foro makes sense, it is necessary to take into account that he was telling this story in 1961 after years of political experience as a Ligas leader, and he was aware that he was speaking to a reporter from one of Brazil’s largest national newspapers. Zezé’s story also fails to explain why the SAPPP leaders would make the landowner honorary president if they had created the organization to combat the rise of rent costs. I believe that instead of judging true and false in this case, a more pressing question is to consider why the coffin story is the most well-known and repeated origin story. Drawing from the trope of o Nordeste, this version emphasizes the connection between misery, poverty, and death and also portrays rural men and women as nonpolitical zealots who are victims of the landowner’s exploitation and Francisco Julião’s brainwashing. In the next section, I further question such assumptions by detailing how the SAPPP turned into a wide-scale social movement that captured national and international attention in the early 1960s.

Transforming the SAPPP into the Galiléia “Revolution”

Led by the ex-administrator of the Engenho Galiléia,12 José Francisco de Souza (velho Zezé) and José dos Prazeres, a group of rural workers from the Engenho Galiliéia traveled to Recife, in early January 1955, to meet with state legislator Francisco Julião at his house outside of Recife, in Caxangá. Julião (PSB, Brazilian Socialist Party) agreed to take their case pro bono, thus beginning the legal process for the expropriation of the Engenho Galiléia. The frequently told origin story often jumps forward from this meeting to the legal victory, in late 1959, but this leap glosses over the processes that took place from 1955 to 1959 to allow the case to even be heard in the state court. During this period, the lawyers and the Galileus had to find ways to gain support for agrarian reform from a broader coalition of rural workers and urban supporters. To do s...